Comments

- No comments found

The Olympic Summer Games were held in Beijing in 2008. Now the Winter Games are being held there in 2022.

For the sake of the athletes who will be inhaling and exhaling more frequently and deeply than usual in the next few weeks, how has the air quality changed? Michael Greenstone, Guojun He, and Ken Lee discuss the evidence in “The 2008 Olympics to the 2022 Olympics: China’s Fight to Win its War Against Pollution” (February 2022, Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago). They write:

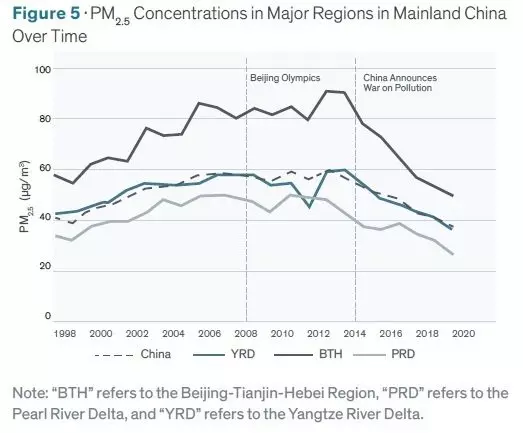

In the years before the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, pollution in China had been sharply climbing. The government responded with quick reforms that temporarily reduced pollution during the games. The reforms, however, only managed to slow the climb in the long run. By 2013, pollution in China had reached record levels. The following year, the same year Beijing applied to host the 2022 Olympic Games, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang declared a “war against pollution” and vowed that China would tackle pollution with the same determination it used to tackle poverty. Seven years later, pollution has declined dramatically by about 40 percent. In Beijing, there is half as much pollution compared to both 2008 and 2013 levels. In most areas of China, pollution has fallen to levels not seen in more than two decades. To put China’s success into context, these reductions account for more than three quarters of the global decline in pollution since 2013. … Due to these improvements, the average Chinese citizen can expect to live 2 years longer, provided

the reductions are sustained. Residents of Beijing can expect to live 3.7 and 4.6 years longer, since 2008 and 2013 respectively.

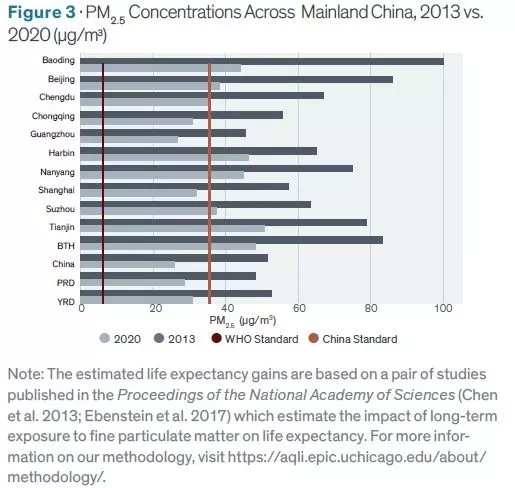

Nevertheless, work remains. While China has met its national air quality standard, pollution levels as of 2020 were still six times greater than the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline. To further reduce pollution, China is taking rapid actions ahead of the 2022 Winter Olympics. If those actions were to allow China to permanently reduce pollution to meet the WHO guideline, the average Chinese citizen could expect to gain an additional 2.6 years of life expectancy, on top of the gains since the war against pollution was initiated. Residents of Beijing could gain an additional 3.2 years.

Here are a couple of figures to illustrate. Pollution is measured here by particulate emissions in the air. This method has the advantage that the data is collected by satellite–not from China’s government. This figure shows how particulate emissions rose in the early 2000s, but have dropped since about 2014.

This next figure shows the change in air particulates in a range of Chinese cities. The black bars are 2013; the gray bars are 2020. The lighter brown bar is China’s pollution standard, which is now being met in many cities; the darker brown bar is the World Health Organization Standard, which is not being met in any Chinese city. As the report notes: “While pollution levels are now on par with its national standards, they are still six times greater than the WHO guideline of 5 μg/m³ as of 2020. Using an international lens, Beijing is still three times more polluted than Los Angeles, the most polluted city in the United States.”

As one might expect, the policy tools used in China to reduce air pollution have lacked subtlety: barring cars from the roads, shutting down industrial plants in certain locations, and so on. The authors note the costs of this command-and-control approach to reducing pollution and the prospect of achieving environmental goals at lower cost with a market-oriented tradeable permit system:

[A]lmost all of the policies come from a “command and control” playbook that generally does not consider how to minimize the costs of achieving their goals. Thus, the Chinese government closed, relocated, and reduced the production capacity of a large number of polluting firms, enforced tighter emission standards across many industries, assigned binding abatement targets to local governments, and sent thousands of discipline teams to inspect local environmental performances. These measures, while being effective in reducing the total emissions in the country, ignored the significant differences in the abatement costs across firms, industries, and regions, and led to large economic and administrative costs in achieving the policy goal. They also led to social media complaints from stakeholders that environmental regulations are too stringent, protests from workers being laid off by the polluting firms, and resistance from local governments for enforcing tighter environmental standards. …

China’s introduction of a national carbon market in July 2021, which upon completion will be the largest such market in the world, positions the country well for the adoption of a particulate pollution and/or sulfur dioxide market.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest