Comments

- No comments found

My standard riff on whether the US dollar will remain the world’s dominant currency going forward (for example, here, here, and here) hits some of these themes: It’s useful for world commerce for many transactions to be done in a single currency.

The dominant currency at any given time has a lot of momentum, and shifts in the dominant currency don’t happen easily. At least so far, the leading candidates to displace the US dollar as the world’s dominant currency, like the euro or the Chinese renminbi yuan, don’t seem to be doing so.

But perhaps the shift away from the US dollar will come with a whisper, rather than with a bang. Serkan Arslanalp, Barry Eichengreen, and Chima Simpson-Bell discuss this possibility in “The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance: Active Diversifiers and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies” (IMF Working Paper, March 2022, WP/22/58).

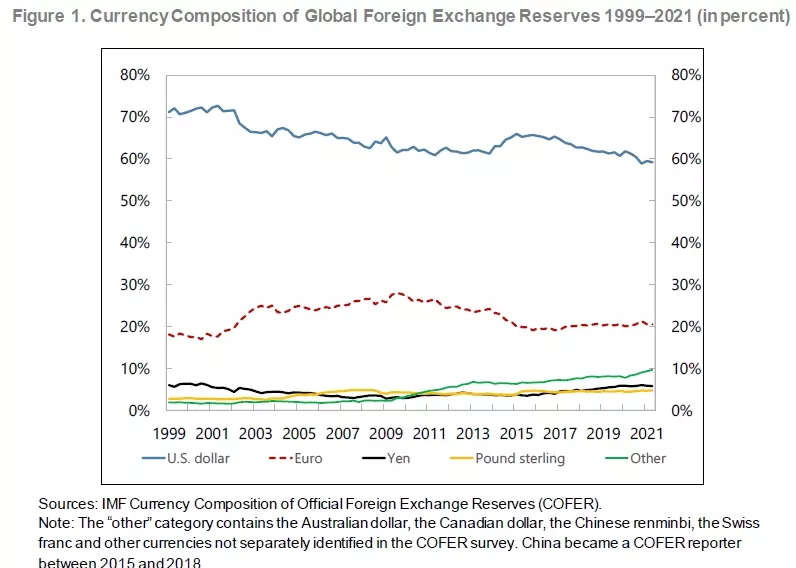

The authors focus in particular on the mixture of currencies that central banks around the world are holding in their foreign exchange reserves. The blue line shows the decline in holdings of the US dollar by central banks from 71% in 1999 to 59% in 2021.

However, the figure also shows that this decline of the US dollar in the foreign exchange holdings of central banks has not been accompanied by a substantial shift to any single alternative currency. The euro, shown by the red dashed line, rose when it was introduced in the early 2000s, but has since fallen back to pretty much the same level. Neither the Japanese yen (black line) nor the British pound (yellow line) has shown much of a rise. Instead, the fall of the US dollar has been accompanied by a rise in the “other” category from 1999. About one-quarter of this increase is the Chinese renminbi. Other currencies playing a notable role here are the Australian dollar, the Canadian dollar, and the Swiss franc.

What is driving central banks to shift their foreign exchange reserves from US dollars to these “other” currencies? The authors suggest several reasons.

First, global financial markets have become much more developed and interconnected in the web-enabled age, making it easier to hold small amounts of “other” currencies. They write: “But as transaction costs have fallen with the advent of electronic trading platforms and now automated market-making (AMM) and automated liquidity management (ALM) technologies for foreign exchange transactions, the savings associated with transacting in U.S. dollars are less. … In addition, the expanding global network of central bank currency swap lines (Aizenman, Ito, and Pasricha, 2021) has enhanced the ability of central banks to access currencies other than the ones they hold as reserves, weakening these links across markets and functions.”

Second, many central banks are holding larger quantities of foreign exchange reserves, which in turn makes it more worthwhile for the central banks to look around at what currencies are paying a higher return. In particular, lower returns on government bonds denominated in the standard reserve currencies (US dollar, euro, Japanese yen, British pound) have made it attractive to seek out and to diversify across other currencies.

These reasons apply more broadly than central banks, of course. It may be that the US dollar is not exactly replaced as the dominant global currency in an abrupt way, but instead is just nibbled away around the edges as it becomes simpler and cheaper to transact in a wide array of currencies.

Here’s one other issue worth considering: Every the United States uses the dominant role of the US dollar in international markets as a policy tool, via economic or financial sanctions, it gives other nations a reason to shift at least somewhat away from reliance on the US dollar as a mechanism for transactions.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest