Comments

- No comments found

There was a time, not so very long ago, when discussions of international trade focused on global talks held through the World Trade Organization.

But the so-called “Doha round” of global trade that started back in 2001 seemed almost dead even a decade ago, and it hasn’t jolted back into life since then.

James McBride, Andrew Chatzky, and Anshu Siriparapu recently updated their “Backgrounder” article for the Council of Foreign Relations on “What’s Next for the WTO?” (June 14, 2021). As they point out, the main multilateral success for WTO in the last decade was a Trade Facilitation Agreement back in 2015 to speed up and coordinate customs for imported products. They also point out that the WTO has shifted from worldwide “multilateral” agreements to “plurilateral” agreements among smaller groups of interested countries focused on a specific set of products. For example, 14 countries pursued an Environmental Goods Agreement about liberalizing trade in products like wind turbines and solar panels and 19 countries are signed on to a Government Procurement Agreement which tries to assure that governments will consider buying imported products when that would benefit taxpayers, rather than just funneling their purchasing power to domestic producers.

The broader shift is that international trade agreements used to be focused on reducing explicit barriers to trade, like tariffs and import quotas. The new wave of regional trade agreements is focused on agreements about assuring common regulations and standards throughout an industry, which can then facilitate global supply chains. These kinds of rules go far deeper than just reducing tariffs and import quotas. For example, imagine the set of health and safe rules that applies if ingredients for a pharmaceutical product are going to be made in different countries and traded across borders, or the set of regulations that applies if insurance or banking services are going to be internationally traded.

These “deep trade agreements” seem both necessary for trade in a modern global economy, and also necessarily more controversial. They are increasingly necessary because world trade is less and less about basic commodities like oil or timber, or basic goods like clothing, and more and more about complex goods and services. But of course, the more a country agrees to detailed agreements for trade, or demands such detailed agreements as a condition for trade, the greater the likelihood that the agreed-upon rules will not actually be about advancing trade, but instead will be about domestic firms and various special interests trying to piggyback their own agendas on to the trade agreement. Or to put it more simply: The analysis of changing tariffs or import quotas is fairly straightforward; the analysis of hundreds of pages of detailed regulations governing trade is messy.

In a recent e-book, Ana Margarida Fernandes, Nadia Rocha, and Michele Ruta have have edited an e-book of essays on these topics titled The Economics of Deep Trade Agreements (CEPR Press, June 2021). Many of the essays provide readable overviews of the key findings of recent research, and I’ll provide a full Table of Contents for the book below. But as example, here are a couple of thoughts from the essay “Lobbying on Deep Trade Agreements: How Large Firms Buy Favourable Provisions,” by Michael Blanga-Gubbay Paola Conconi, In Song Kim, and Mathieu Parenti.

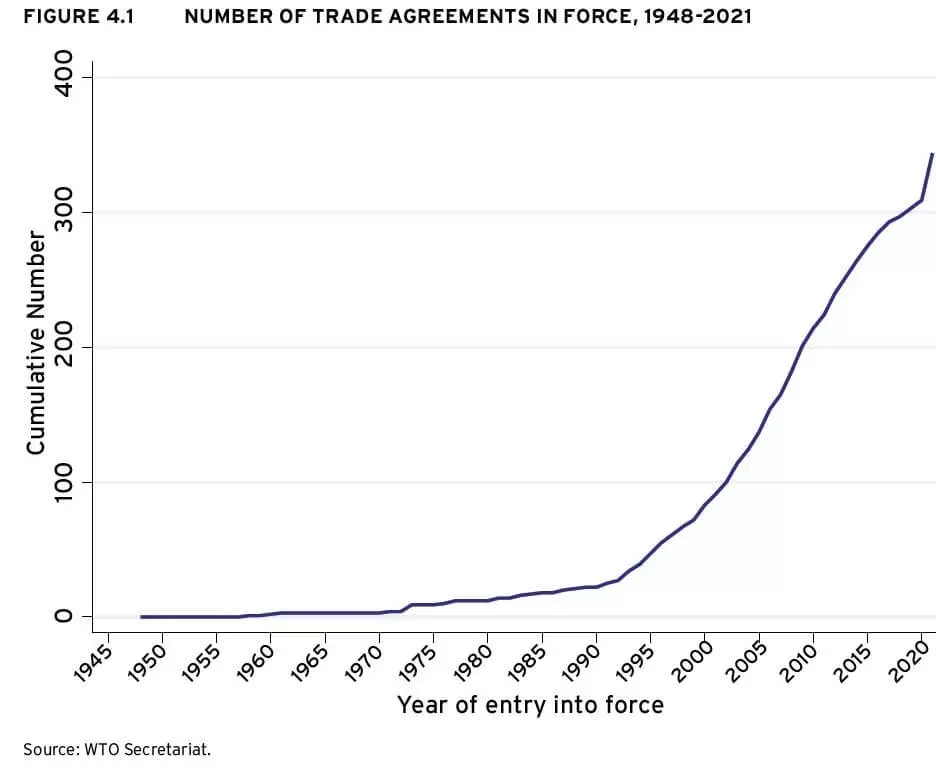

The authors point to the sharp rise in the number of regional and bilateral trade agreements in the last 25 years:

The authors point to a recent data set that contains detailed information on the provisions of current trade agreements in 17 areas. As they write:

Some of these deep trade issues are related to trade policies: Export Restrictions, Rules of Origin, Trade Facilitation and Customs, and Trade Remedies. Others concern non-trade policies: Intellectual Property Rights, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, Technical Barriers to Trade, Public Procurement, Subsidies, Services Investment, Movement of Capital, Visa and Asylum, State Owned Enterprises, Competition Policy, Environmental Laws, and Labour Market Regulations.

In addition, several of the essays point out, the question of how (or whether) the rules will be enforced is of key significance: Domestic courts in the exporting or importing country? Arbitrators? International tribunals? The authors also refer to an essay by Dani Rodrik in the Spring 2018 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives (where I work as Managing Editor).

To illustrate the increase in depth of trade agreements, Rodrik (2018) compares US trade agreements with two small nations, Israel and Singapore, signed two decades apart. The US-Israel agreement, which went into force in 1985, is less than 8,000 words in length and contains 22 articles and three annexes, mostly devoted to trade issues such as tariffs, agricultural restrictions, import licensing, and rules of origin. By contrast, the US-Singapore agreement, which went into force in 2004, is nearly ten times as long, taking up 70,000 words and containing 20 chapters, more than a dozen annexes, and multiple side letters. Of its 20 chapters, seven cover conventional trade topics, while the others deal with behind-the-border topics. For example, provisions on intellectual property rights take up a third of a page (and 81 words) in the US-Israel agreement; they occupy 23 pages (and 8,737 words) plus two side letters in the US-Singapore agreement.

_____________

Here’s the full Table of Contents for the book:

“Introduction: The economics of deep trade agreements,” by Ana Margarida Fernandes, Nadia Rocha, and Michele Ruta

The economic impact of deep trade agreements

1 “The enduring role of international integration in development,” by Pinelopi Goldberg and Tristan Reed

2 “Quantifying the impact of deep trade agreements: A general equilibrium

approach,” by Lionel Fontagné,Nadia Rocha, Michel Ruta, and Gianluca Santoni

3 “Using machine learning to assess the impact of deep trade agreements,” by Holger Breinlich, Valentina Corradi, Nadia Rocha, Michele Ruta,

João. M.C. Santos Silva, and Tom Zylkin

Political economy and design of deep trade agreements

4 “Lobbying on Deep Trade Agreements: How Large Firms Buy

Favourable Provisions,” by Michael Blanga-Gubbay, Paola Conconi, In Song Kim, and Mathieu Parenti

5 “Global value chains and deep integration,” by Leonardo Baccini, Matteo Fiorini, Bernard Hoekman, Carlo Altomonte, and Italo Colantone

6 “Pro-competitive provisions in deep trade agreements,” by Meredith A. Crowley, Lu Han, and Thomas Prayer

Protectionism at the border and beyond

7 “The impact of preferential trade agreements on the duration of antidumping protection,” by Thomas J. Prusa, and Min Zhu

8 “Trade facilitation provisions in deep trade agreements: Impact on Peru’s exporters,” by Woori Lee, Nadia Rocha, and Michele Ruta

9 “Heterogeneous impacts of sanitary and phyto-sanitary and technical barriers to trade regulations: Firm-level evidence from deep trade agreements,” by Ana Margarida Fernandes,Kevin Lefebvre, and Nadia Rocha

Services trade and state intervention

10 “Scoping services trade agreements: What really matters,” by Ingo Borchert and Mattia Di Ubaldo

11 “Trade barriers in government procurement,” by Alen Mulabdic and Lorenzo Rotunno

12 “The spillover effect of deep trade agreements on Chinese state-owned enterprises,” by Kevin Lefebvre, Nadia Rocha, and Michele Ruta

Non-trade issues in trade agreements

13 “How preferential trade agreements with strong intellectual property provisions affect trade,” Keith E. Maskus and William Ridley

14 “Deep integration in trade agreements: Labour clauses, tariffs, and trade flows,” by Raymond Robertson

15 “Trade agreements with environmental provisions mitigate deforestation,” Ryan Abman, Clark Lundberg, and Michele Ruta

Conclusion

16 Why deep trade agreements may shape post-COVID-19 trade,” by Aaditya Mattoo, Nadia Rocha, and Michele Ruta

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest