For a lot of people, the idea of negative interest rates sounds as if it must violate some law of nature, like a perpetual motion machine.

Why would any depositor put money into an investment that promised a negative return? Well, starting way back in 2012, a substantial number of central banks around the world including the European Central Bank, the Swiss National Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the Sveriges Riksbank (the central bank of Sweden) have pushed the specific interest rates on which they focus monetary policy into negative territory for the last several years. Luís Brandão-Marques, Marco Casiraghi, Gaston Gelos, Güneş Kamber, and Roland Meeks offer an overview of the experience in "Negative Interest Rates: Taking Stock of the Experience So Far" (IMF Monetary and Capital Markets Department, 21-03, March 2021).

Perhaps the obvious questions about a negative interest rate is why depositors would put money in the bank at all. The short answer is that banks provide an array of financial services to both businesses and individual customers (ease of electronic payments, not needing to hold large amounts of cash, access to credit, and so on). As a customer, you can pay for those services with some combination of fees and lower interest rates. It's easy to imagine a situation where slightly negative interest rates are offset by changes in other fees or contractual arrangements.

It's also worth remembering that the fact of a negative interest rate in real terms is not actually new at all. At many times in the past, people have experienced negative real interest rates on their bank deposits--that is, when the inflation rate is higher than the nominal interest rate, the real interest rate is negative.

Of course, if the bank interest rates became too negative, then depositors would indeed move away from banks and toward cash or other alternative investments. What is the "effective lower bound" for a negative interest rate? The answer will depend on various assumptions about the financial system, including costs of setting up companies that store large amounts of cash, but here's a set of estimates from various studies.

Given that slightly negative bank interest rates are clearly possible, what are their benefits and risks?

On the benefit side, when a central bank acts to lower interest rates, its goal is to stimulate the economy, both to encourage growth and also to raise inflation if that rate is below the desired target level (often set at 2%). Thus, the key question is whether moving the bank policy interest rate below zero does provide some additional macroeconomic boost. The specific effects of negative interest rates aren't easy sort out on their own, because central banks that have moved their policy interest rate into negative territory have also been carrying out other unconventional monetary policies like quantitative easing setting explicit forward guidance for what monetary policy will be in the near-term or middle-term future, or intervening in exchange rate markets. But as this report summarizes the evidence: "For instance, the transmission mechanism of monetary policy does not appear to change significantly when official rates become negative."

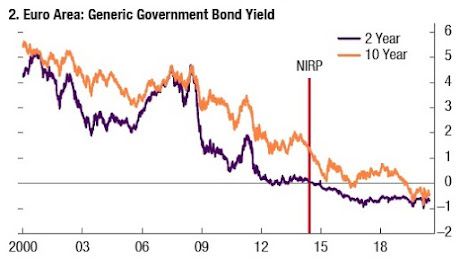

As one example of how negative interest rate policies reduce actual interest rates, this figure shows how the returns on euro-denominated government debt have dipped into negative terms.

On the risk side, perhaps the main danger was that negative interest rates would cause large losses for banks or other major players in the financial system like money market funds. But again, at least so far, these problems have not emerged. The report notes:

Overall, most of the theoretical negative side effects associated with NIRP [negative interest rate policies] have failed to materialize or have turned out to be less relevant than expected. Economists and policymakers have identified a number of potential drawbacks of NIRP, but none of them have emerged with such an intensity as to tilt the cost-benefit analysis in favor of removing this instrument from the central bank toolbox. ... [O]verall, bank profitability has not significantly suffered so far ... and banks do not appear to have engaged in excessive risk-taking. Of course, these side effects may still arise if NIRP remains in place for a long time or policy rates go even more negative, approaching the reversal rate.

However, it's worth noting that the negative interest rates in place have mainly affected large institutional depositors. For households and retail investors, banks have tried to keep the interest rates they receive in slightly positive territory--but have also adjusted other fees and charges in ways that have sustained bank profitability. As the report notes: "Banks seem to respond to NIRP by increasing fees on retail deposits, while passing on negative rates partly to firms."

The IMF report also identifies areas where research on negative interest rates policies has been limited.

The literature so far has largely overlooked the impact of negative interest rates on financial intermediaries other than banks. Although pension funds and insurance companies do not typically offer overnight deposits and thus the constraint on lowering the corresponding rates below zero is not an issue, other non-linearities may arise when market rates become negative. Among others, legal or behavioral constraints to offering negative nominal returns could affect the profitability of nonbanks. Given the importance of these institutions for the financial system, the absence of empirical evidence on the impact of negative rates on their behavior is surprising. ..

Another interesting direction for future research is to further study the determinants of the corporate channel identified by Altavilla and others (2019b). According to this channel, cash-rich firms with relationships with banks that charge negative rates on deposits are more likely to use their liquidity to increase investment. What drives this channel is still unclear. For instance, the role of multiple bank relationships could be investigated. If cash-rich firms can easily move their liquidity across financial institutions (including nonbanks), then negative rates on corporate deposit may simply lead these firms to reallocate their liquidity across intermediaries, without any significant impact on investment. By contrast, frictions that prevent firms from easily establish new bank relationships, and thus move their funds around, could induce a reallocation from corporate deposits to other less liquid assets, such as fixed capital.

In my reading, the general tone of the IMF report is that the negative interest rate policies have been modestly useful, and without worrisome negative side effects--but also that central banks have a number of other options for unconventional monetary policy and while particular option should be in the toolkit of options, it perhaps should not be pushed too hard.

For some additional discussion of negative interest rates, including the previous IMF staff report on the subject back in 2017 and various other sources, starting points include:

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest