Comments

- No comments found

As the population ages, it seems plausible that more people will rely on long-term care.

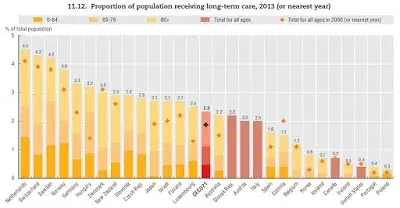

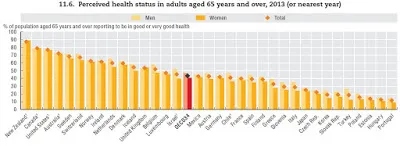

Such care could be delivered in a variety of ways: for example, within their own home, or a specialty adapted house where care is available 24/7, or or in an institutionalized setting, and by some mixture of paid providers, volunteers, and family members. Compared with other high-income nations of the world, the US is something of an outlier when it comes to long-term care: spending less, fewer recipients of long-term care, as a result a healthier over-65 population. The figures below come from the OECD data book published a couple of years ago.

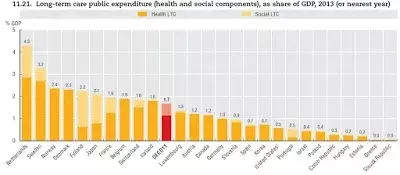

Here’s a figure showing public spending on long-term care as a share of GDP. The OECD average is 1.7% of GDP. The US spends 0.5% of GDP. The other countries that spend this little tend to have lower GDP per capita than the rest of this comparison group.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest