Comments

- No comments found

The idea of a “tax expenditure” dates back to Stanley Surrey, who was Assistant Secretary of the US Treasury for Tax Policy back in the 1960s.

He pointed out that certain government programs could be implemented either through direct spending or through the tax code: for example, the government could either cut checks to subsidize research and development by firms, or it could offer them a tax credit for doing so. The first list of tax expenditures was produced in 1967; it’s been an official part of the federal budget since 1974.

Just to be clear, calling something a “tax expenditure” is not meant to carry a positive or a negative connotation. There can be good and sensible reasons why some policies operate through the tax code and others do not. But there had been concern that enacting a policy through the tax code could make it appear “free”–because after all no direct spending was involved. Instead, it seemed useful to at least be aware of the dollar magnitude of tax expenditures, as a starting point for a reasonable discussion of whether they were sensible policies.

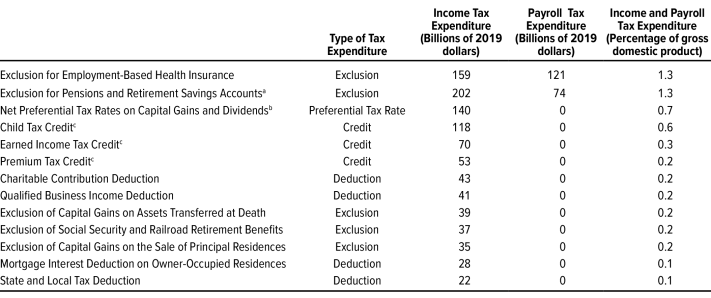

The Congressional Budget Office has just published The Distribution of Major Tax Expenditures in 2019 (October 2021). This report evaluates tax expenditures along just one dimension: who receives the benefits by income group? Here’s the list of the major tax expenditures by dollar amount:

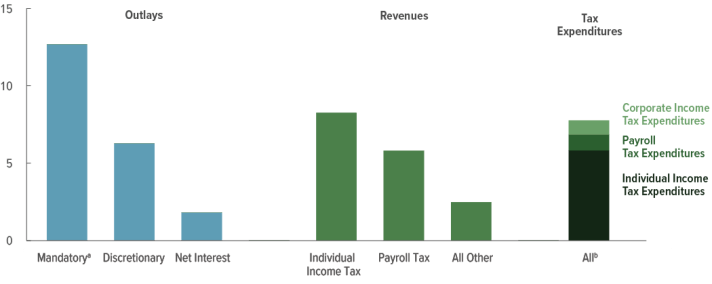

To give a sense of perspective, here’s a graph showing the total of these major tax expenditures relative to some other main categories of spending and taxation. The total for tax expenditures is higher than for federal discretionary spending, and almost as much as revenues from the federal income tax.

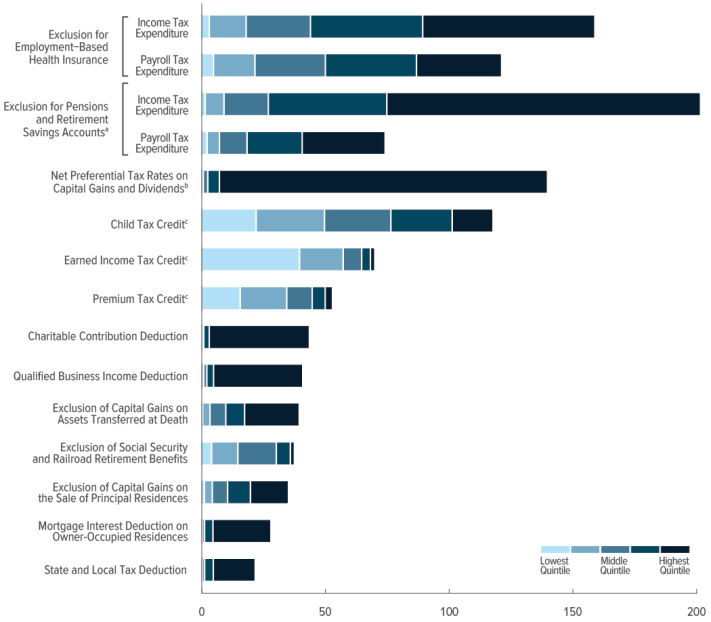

As you look through the list of major tax expenditures , you may notice that the distributional effects of these provisions are likely to be greater either at the top or at the bottom of the income distribution. If you look at the top couple of provisions, which involve employer-provided health and retirement benefits where the value is excluded from taxable income, these provisions will always tend to be more valuable for those with higher incomes, who would have been paying higher tax rates, than for those with lower incomes who would have been paying lower tax rates. On the other side, the Child Tax Credit, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Premium Tax Credit all are focused on those with relatively low income levels and phase out as incomes rise.

This figure shows the distribution of tax expenditures by income quintile. The darkest bars refer to the top income quintile; the lightest bars to the lowest income quintile.

The result of this pattern is that if you look at these major tax expenditures in dollar amount, most of the benefits flow to the top quintile of income–and indeed to the upper part of the top quintile.

However, if you look at these tax expenditures as a share of income, it turns out that they are more important to those with lower income levels.

Each of these tax expenditure provisions is worthy of individual examination. In my own mind, for example, employer-provided health insurance should be taxed as income, because the benefit is directly received in that year. However, I don’t have a problem in general with excluding payments to retirement accounts from taxation, as long as that income is taxed when it is actually received in the future. But the main theme here is just to bring these tax expenditures, and their distributional consequences, out into the light.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest