Comments

- No comments found

World War II did cause some short-term disruptions and shortages in the US economy.

There’s a conventional story that World War II was a boost for the US economy, both providing a burst of aggregate demand that ended the Great Depression, and also establishing the basis for several decades of postwar prosperity in US manufacturing. Alexander J. Field begs to differ. He lays out his case in “The decline of US manufacturing productivity between 1941 and 1948” (Economic History Review, published online January 16, 2023).

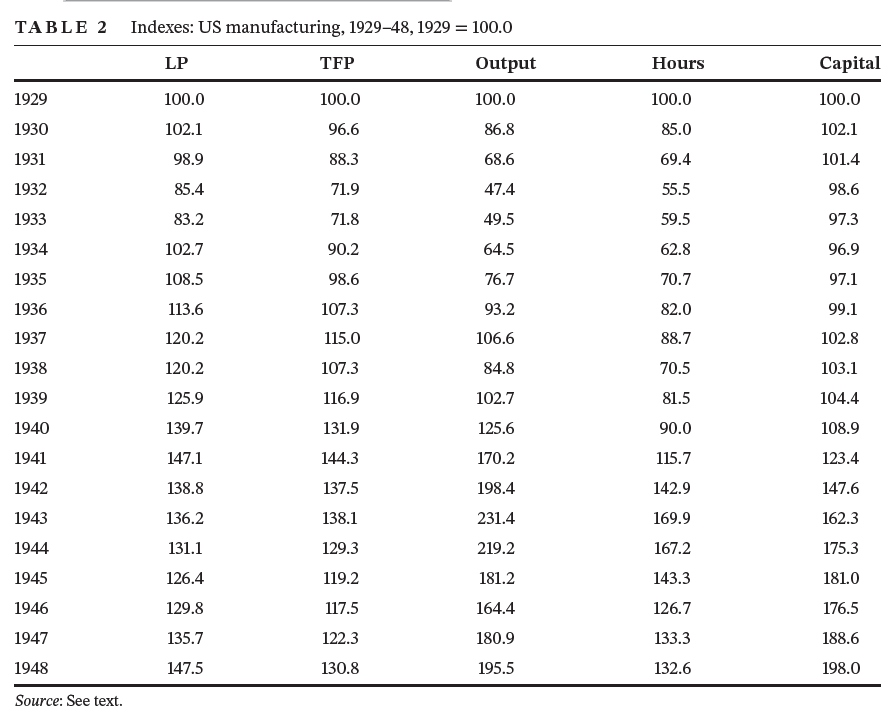

Of course, total manufacturing output did rises substantially during World War II, but “productivity” for economists doesn’t refer to total output. Instead, productivity refers to output per hour worked–or more generally, output relative to given inputs of labor and capital. With that in mind, you can get some of the flavor of the larger perspective of Field’s argument by taking a look at this data on the US manufacturing sector form 1929 to 1948. As you see, everything is expressed relative to 1929: that is, the level of all the variables is set at 100 for 1929. The first column is labor productivity, or output per hour. The second is “total factor productivity,” a more complex (although by no means truly difficult) calculation that is output per combined inputs of labor and capital. The third column is total manufacturing output; the fourth columns is hours worked in the manufacturing sector, and the last column is stocks of capital in the manufacturing sector.

Before looking at the World War II years, just run your eyes over the 1930s for a moment to get a sense of how this works–and perhaps to reset your perceptions of what happened during this time. Manufacturing output falls by half during the Great Depression from 1929 to 1933. The stock of capital equipment doesn’t fall by much during this time: after all the equipment may have been less used or unused, and some of it would wear out, but the equipment itself was mostly still there. Hours worked in manufacturing falls 40% from 1929 to 1933, which is less than the fall in output. Thus, output per hour worked, as shown in the first column falls substantially from 1929 to 1933.

There is a common perception that the Great Depression lasted throughout the 1930s, before the economy was jolted out of the Depression by World War II spending. The table shows that this perception is untrue. Manufacturing output doubles from 1933 to 1937. The economy is then jolted by a sharp increase in interest rates by the Federal Reserve leading to a steep recession in 1937-38–and then followed by a doubling of manufacturing output from 1938-1941. Readers will remember that while there is certainly fear of war in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the actual entry of the US into World War II doesn’t happen until Decemer 1941.

As the US scrambled to reshape its economy to a wartime footing, output rises substantially. But there are also substantial jumps in labor and capital inputs. Thus, both labor productivity (output per hour worked of labor) and total factor productivity (output per unit of inputs including labor and capital) start to decline. Field described the underlying process this way:

The [productivity] declines in 1942 reflect, above all else, the chaotic conditions associated with the changes in the product mix. Productivity took a huge hit as machinery to produce peacetime products made way for newly designed machine tools, and labour and management struggled to become proficient as they moved from making goods in which they had a great deal of experience to those in which they had little. Shortages, hoarding of inputs, and production intermittency plagued the war effort. The positive effects of learning by doing are evident in the change in both labour productivity and TFP growth between 1942 and 1943. They were nevertheless insufficient to compensate for the sharp drop during the previous year. Productivity resumed an accelerated decline in 1944, as a secondary round of major product changes kicked in, and was even more negative in 1945, due in part to the disruptions associated with demobilization. Partial recovery between 1945 and 1948 still left the TFP level in US manufacturing substantially below where it had been in 1941.

There is a conventional narrative about World War II that it was at least “good for the economy,” but that seems imprecisely put. It’s true that the US economy, with its high level of technical skills and extraordinary flexibility, was very good indeed for winning the war–which was clearly the highest priority at that time. But the war led to multiple dramatic disruptions in the US economy: restructuring to wartime production in multiple ways and times, labor shortages, supply shortages, and then a dramatic restructuring back to a peacetime economy.

Field offers a reminder that much of the capital investment made during World War II was useless at the end of the war.

With the temporary exception of B-29 bombers, most of the aircraft produced during the war were, at its conclusion, deemed surplus: obsolete or unneeded. Tens of thousands were flown to boneyards in Arizona: air bases such as Kingman and Davis-Monthan. … Some aircraft were flown directly from the factory gate to Arizona for disassembly and recycling. Many aircraft operating overseas were never repatriated. It was simply not worth the cost in fuel and manpower to fly them back to the United States so they could be scrapped. Similar fates befell Liberty ships (scrapped and recycled for the steel), tanks, and other military equipment including field artillery. …

There was indeed a huge investment in plant and equipment by the federal government. But the mass production techniques that made volume production of tanks and aircraft possible in the United States relied overwhelmingly on single- or special-purpose machine tools, and most of these tools and related jigs and frames were scrapped with reconversion. The United States did use multipurpose machine tools, which could more easily be repurposed, but this was principally in the shops producing machine tools. Already in 1944, the country confronted serious

surplus and scrappage issues. By early 1945 disposal agencies had surplus inventories of roughly $2 billion – equivalent to the entire cost of the Manhattan Project. By V-J Day that had risen to US $4 billion, and ultimately to a peak of US $14.4 billion in mid-1946. …

Both public and private capital accumulation in areas not militarily prioritized had been repressed.Wartime priorities starved the economy of government investment in streets and highways,

bridges and tunnels, water and sewage systems, hydro power, and other infrastructure that had played such an important role in the growth of productivity and potential output across the

Depression years. These categories of government capital complementary to private capital grew at a combined rate of 0.15 per cent per year between 1941 and 1948, as opposed to 4.17 per cent per year between 1929 and 1941.81. Portions of the private economy not deemed critical to the war effort also subsisted on a thin gruel of new physical capital. Trade, transportation, and manufacturing not directly related to the war are cases in point. Private nonfarm housing starts,which had recovered to 619 500 in 1941, still 34 per cent below the 1925 peak (937 000), plunged to 138 700 in 1944, barely above the 1933 trough of 93 000. All ‘nonessential’ construction in the country was restricted beginning on 9 October 1941, almost two months before the Japanese attack.82

Of course, the US economy suffered a terrible loss of workers as a result of World War II. “As for labour, the immediate post-war impact of the war on potential hours was clearly negative: 407 000 mostly prime-age males never returned. Most would have been alive in the absence of the war. …There were another 607 000 military casualties. The 50 per cent wartime rise in female labour-force participation largely dissipated during the immediate

post-war period.

What about new technologies developed during World War II? As Field points out, the ability to run extraordinary assembly lines for making planes and ships was not a useful technology after the war ended. More broadly, he argues that World War II was more about taking advantage of technologies that had been developed earlier, not about the invention of technologies that would have lasting benefits in peacetime.

What of more general scientific and technological advance? Kelly, Papanikolaou, Seru, and Taddy digitized almost the entire corpus of US patent filings between 1840 and 2010, and analysing word counts, identified breakthrough patents: those that were novel at the time and influential afterwards. Such patents had low backward similarity and high forward similarity scores … Their time series of such patents shows a peak in the 1930s, particularly the first half of the decade, and a noticeable trough during the war years …

Much of what occurred during the war represented the exploitation of a preexisting knowledge base. In 1945, Vannevar Bush published Science, the endless frontier, a work often viewed as distilling the lessons and achievements of the war into an actionable blueprint for post-war science and technology policy. However, as David Mowery noted, ‘the Bush report consistently took the position that the remarkable technological achievements of World War II represented a depletion of the reservoir of basic scientific knowledge’...

It is of course impossible to re-run history and see what would have happened if the economic trends of the late 1930s had continued without the interruptions, costs, and material and human losses of World War II. But it is surely possible that the US have had a stronger economy in 1950 if it had not suffered losses of a million killed and wounded, and had not needed to scramble its outputs first to a wartime and then to a peacetime footing, and had been able to pursue non-war science and technology. Field goes so far as to speculate: “From a long-run perspective, the war can be seen, ironically, as the beginning of the end of US world economic dominance in

manufacturing.”

Given this kind of evidence, why is the belief in the economic benefits of World War II so deeply rooted? Field quote Elizabeth Samet’s argument that there is “pernicious American sentimentality about nation” and that “we search for a redemptive ending to every tragedy.” There is surely some truth in this, but perhaps a simpler truth is that the losses and costs of World War II are too staggering to contemplate.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest