One of those things that "everyone knows" is that continued technological progress is vital to the continued success of the US economy, not just in terms of GDP growth (although that matters) but also for major social issues like providing quality health care and education in a cost-effective manner, addressing environmental dangers including climate change, and in other ways. Another thing that "everyone knows" is that research and development spending is an important part of generating new technology. But total US spending on R&D as a share of GDP has been nearly flat for decades, and government spending on R&D as a share of GDP has declined over time.

Here's a figure on funding sources for US R&D from the Science and Engineering Indicators 2018. The top line shows the rise in R&D spending in the 1960s (much of it associated with the space program and the military), a fall in the 1970s, and then how R&D spending has bobbed around 2.5% of GDP since then. The dark blue line shows the rise in business-funded R&D, while the light blue line shows the fall in government funding for R&D.

One underlying issue is that business-funded R&D is more likely to be focused on, well, the reasonably short-term needs of the business, while government R&D can take a broader and longer-term perspective,

One signal of this dynamic is that the share of patents which rely on government funding is on the rise. L. Fleming, H. Greene, G. Li, M. Marx, and D. Yao describe the pattern in "Research Funding: Government-funded research increasingly fuels innovation" (Science, June 21, 2019, pp. 11139-1141).

Of course, the relationship between R&D spending and broader technological progress is complicated. Translating research discoveries into goods and services isn't a simple or mechanical process. Other important elements include the economic and regulatory environment for entrepreneurs, the diffusion of new technologies across firms, and the quantity of scientists and researchers. For an overview of the broader issues, Nicholas Bloom, John Van Reenen, and Heidi Williams offer "A Toolkit of Policies to Promote Innovation"in the Summer 2018 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives. They explain the case for government support of innovation:

Knowledge spillovers are the central market failure on which economists have focused when justifying government intervention in innovation. If one firm creates something truly innovative, this knowledge may spill over to other firms that either copy or learn from the original research—without having to pay the full research and development costs. Ideas are promiscuous; even with a well-designed intellectual property system, the benefits of new ideas are difficult to monetize in full. There is a long academic literature documenting the existence of these positive spillovers from innovations. ...

As a whole, this literature on spillovers has consistently estimated that social returns to R&D are much higher than private returns, which provides a justification for government- supported innovation policy. In the United States, for example, recent estimates in Lucking, Bloom, and Van Reenen (2018) used three decades of firm-level data and a production function–based approach to document evidence of substantial positive net knowledge spillovers. The authors estimate that social returns are about 60 percent, compared with private returns of around 15 percent, suggesting the case for a substantial increase in public research subsidies.

Along with pointing out some advantages of government-funded R&D, Bloom, van Reenen, and Williams also point out that when it comes to tax subsidies for corporate R&D, the US lags well behind. They write:

The OECD (2018) reports that 33 of the 42 countries it examined provide some material level of tax generosity toward research and development. The US federal T&D tax credit is in the bottom one- third of OECD nations in terms of generosity, reducing the cost of US R&D spending by about 5 percent. ... In countries with the most generous provisions, such as France, Portugal, and Chile, the corresponding tax incentives reduce the cost of R&D by more than 30 percent. Do research and development tax credits actually work to raise R&D spending? The answer seems to be “yes.”

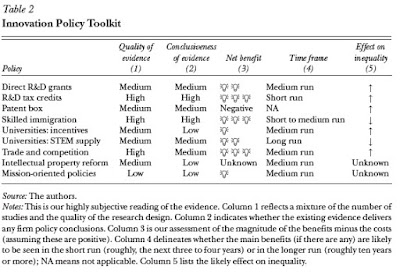

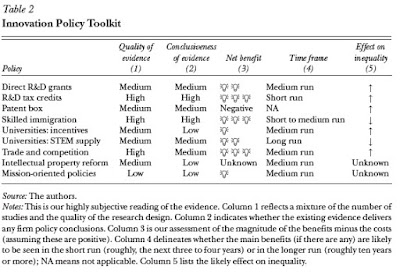

Here's their toolkit of pro-innovation policies, with their own estimates of effectiveness along various dimensions.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest