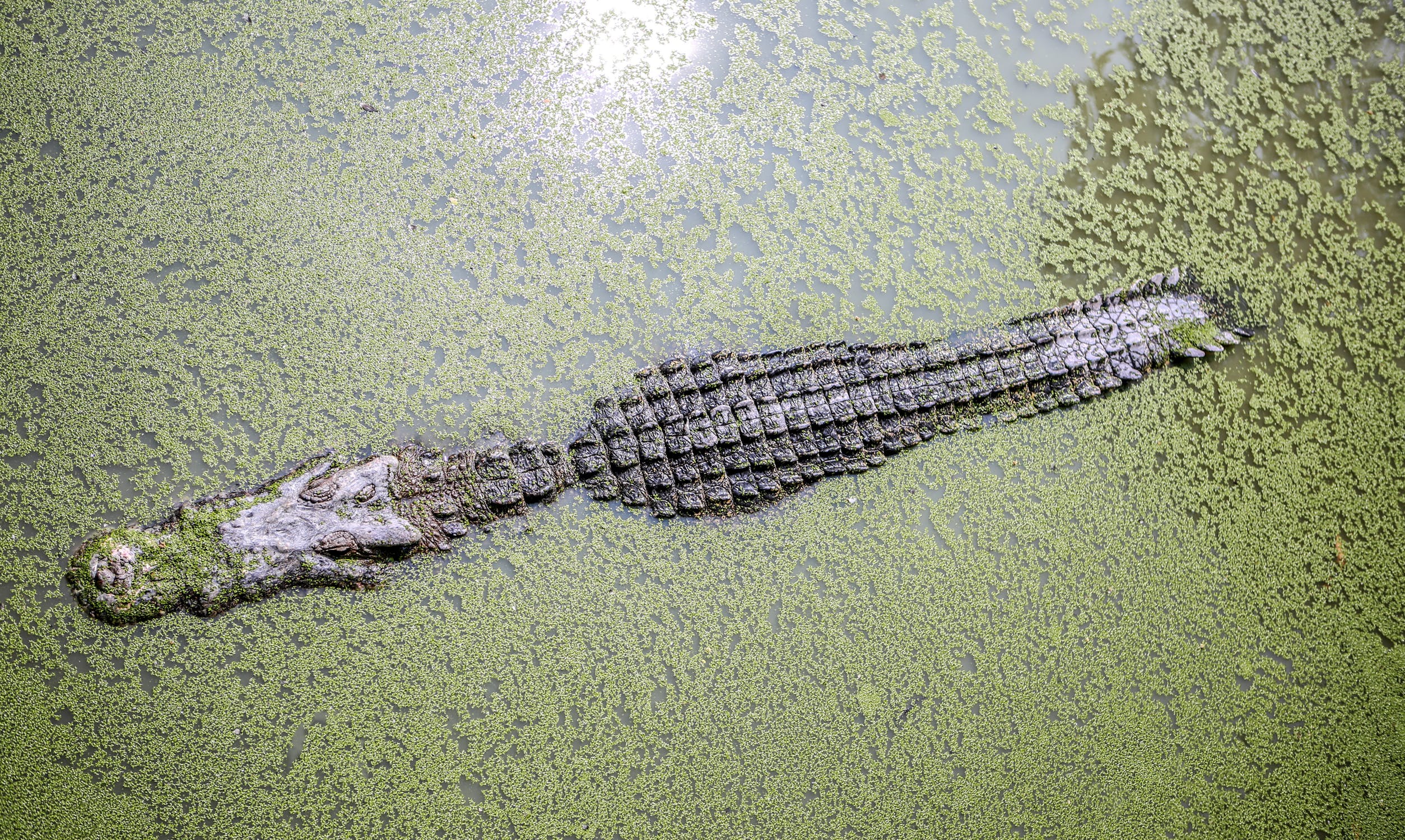

"About half a century ago, the American alligator became one of the original endangered species. Today, there are approximately 1.3 million in Florida alone, and residents routinely call nuisance trappers ... to remove gators from swimming pools, neighborhood lagoons, and pretty much any other body of water they find their way into. For the nuisance trappers across the state, markets and commercialization are part of the foundation that helps manage this now-abundant species."

Tate Watkins describes the situation in "The Gator Traders: Markets help manage alligators in Florida. What can they teach us about managing other abundant species?"published in PERC Reports, Summer 2019, pp. 32-29).

Florida has a hunting season for alligators: "The wildlife commission issued more than 6,000 harvest permits in 2017, when roughly 6,200 alligators were killed. (Each permit allows a hunter to take two gators.) A resident permit currently costs $272 (out of state permits run to $1,022), and the statewide hunt generated about $1.8 million last year." But what happens when you find an alligator in the pond in your backyard, who are you going to call?

The answer in Florida is the Statewide Nuisance Alligator Program hotline, who contacts a "nuisance trapper." "In 2018, the 110 nuisance alligator trappers in Florida harvested 8,139 nuisance alligators from more than 14,000 complaints." The state pays $30 for each nuisance alligator. If the alligator is less than four feet long, it needs to be transported and released back into the wild. But the real incentive is that if the alligator is more than four feet long, the trapper is allowed to harvest the hide and meat and sell them. Without this incentive, the nuisance trappers wouldn't come close to covering their expenses on the state's $30 payments--which come from a fund that usually runs out well before the end of the year, anyway.

In this way, the Florida Statewide Nuisance Alligator Program offers an interesting blend of how to manage an environmental resource using elements of markets. Indeed, one problem for the program is that the price of alligator hides has recently dropped:

A few decades ago, when the market was booming, Florida wild gator hides reportedly sold for up to $35 a linear foot. Now, trappers hope their skins might fetch $7 a foot if they’re fortunate. (Stephens, who has been a nuisance trapper for less than a decade, says he once sold hides for $28.50 a linear foot but now can hardly find a bulk buyer.) Plus, Stephens explains, he and others in the sector fight the perception that “you trappers are getting rich off the hides,” as he says a state politician put it to him once. He showed the legislator his mileage logs for nuisance calls. At a cost of nearly $200 per gator, Stephens says he was much closer to breaking even than getting rich from trapping.

The idea of using market incentives to manage wildlife and game is not especially common, but neither is it unknown. Watkins points out the Australian kangaroo market as another example:

That’s basically the approach that Australia has taken to manage its estimated 50 million kangaroos, which damage crops, forage pastures, and destroy fairways across much of the country. Licensed cullers are permitted to hunt ’roos and sell their game products to processors and distributors. In recent years, the kangaroo market has evolved and broadened, as National Geographic recently reported: “Global brands such as Nike, Puma, and Adidas buy strong, supple ‘k-leather’ to make athletic gear. And kangaroo meat, once sold mainly as pet food, is finding its way into more and more grocery stores and high-end restaurants.” Australia sells kangaroo products to more than 50 countries and earned $29 million in exports from the animal products in 2017.

Market forces are clearly powerful enough to threaten species with extinction: indeed, market forces from hunting to land development are why the alligator nearly became extinct. Another prominent example that I've discussed of market forces driving a species to near-extinction is the American buffalo (see here and here). Clearly, the power of an unregulated and unrestrained market can be environmentally destructive. But the the power of a regulated and restrained market can be a tool for environmental gains (for example, via cap-and-trade pollution permits) and wildlife management, too.

A version of this article first appeared on Conversable Economist.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest