Comments

- No comments found

It’s not a big shock that those who get a PhD tend to have parents who also had a higher level of education.

If your parents have some knowledge about how to navigate the tangled forests of academia, along with the financial resources to help you along, you are more likely to get that advanced degree. But what is surprising, at least to me, is that this connection between parental education and getting a PhD is stronger for economics than for most other fields.

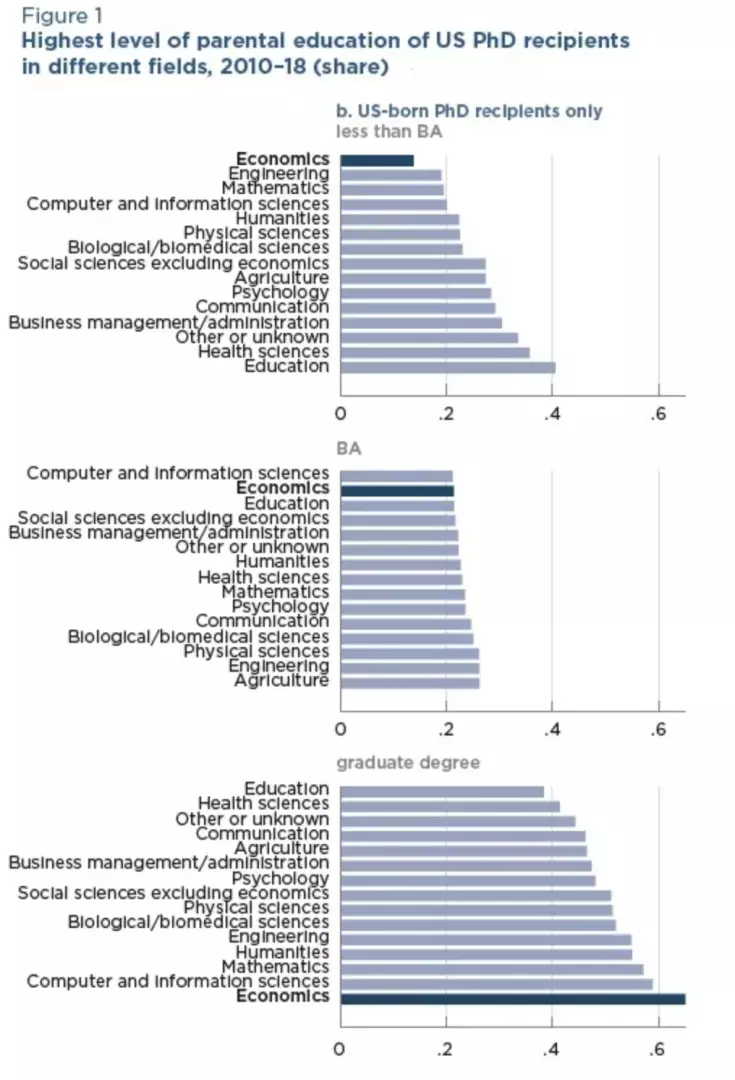

Robert Schultz and Anna Stansbury provide the facts in “Socioeconomic Diversity of Economics PhDs” (March 2022, Peterson Institute for International Economics, WP-22-4). This figure shows some of the background. The first panel shows, in each field, what share of those with PhDs have parents who did not complete a college degree. Economics is the lowest. The second panel shows what share of those with PhDs in a given field have parents who completed a college degree, but not an additional degree. Economics is near the top. The third panel shows what share of those with PhDs in a given field have parents who completed a graduate degree in some field (not necessarily the same one).

One possible concern here is that many PhD programs at American universities have a large share of international students. Perhaps the patterns would be different if we focused only on US-born PhDs? Not really. Here are the same figures, this time with only US-born PhDs. As you can see, US-born economics PhDs are least likely to have parents without a BA degree and most likely to have parents with an advanced degree. It’s true that economics PhDs don’t look different in the middle graph of those with only a BA degree, but it’s also true that the differences in that middle graph across different PhD fields are relatively small.

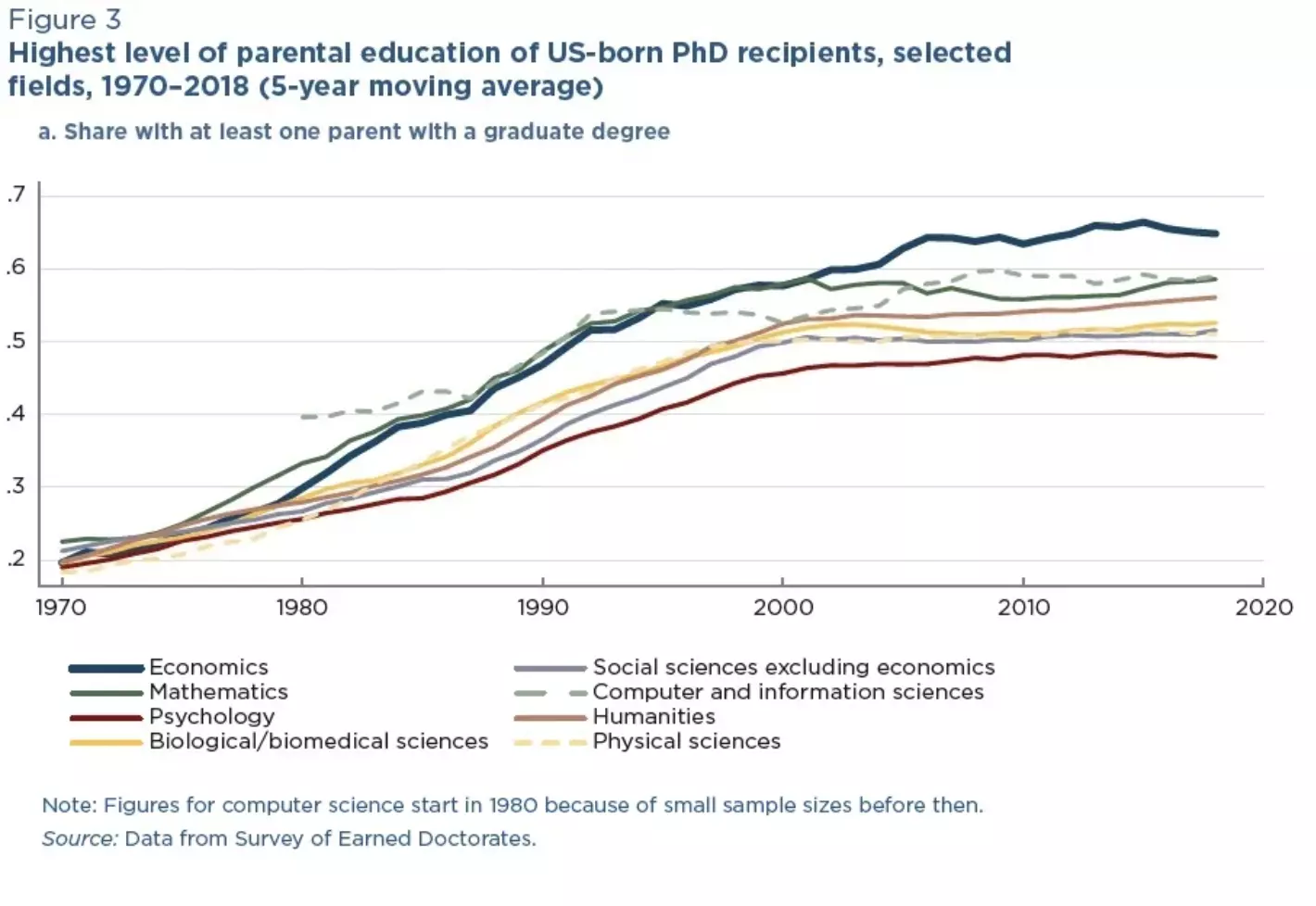

This distinctive pattern of economics PhDs seems to have emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, and remained that way since then. This graph shows the connection between whether a parent has an advanced degree and an individual’s likelihood of getting a PhD. The overall pattern here is interesting: across many fields, those who get PhDs are more likely to have parents with advanced degrees. For many other fields, this pattern has flattened out in the last couple of decades: in economics, not so much. There is a broader social issue here, which is that higher education has become a way for the well-off to give their children a socioeconomic boost as well–an intergenerational social mechanism that is probably much more important for most families than the size of any purely financial inheritance. But my focus here is on the pattern for economics PhDs, where this overall pattern is strongest.

Why does economics stand out from other subject areas in these comparisons? The answer isn’t obvious. One possibility is that the gap between a BA degree and PhD study is large in most fields, but maybe largest in economics. In most economics programs, it’s possible to get high grades in all your required classes and your senior project, but if you have not taken an additional heavy dose of math and statistics beyond those requirements, or if your undergraduate department hasn’t prepared you for graduate school expectations in other ways, you are less likely to be admitted and to succeed in an economics PhD program. Perhaps parents with graduate degrees are more aware of these issues, and so their children who go on to enter an economics PhD program are better prepared.

Another theory is that there is something in the way economics is commonly presented or taught at the undergraduate level which makes it less appealing to students whose parents do not have graduate degrees.

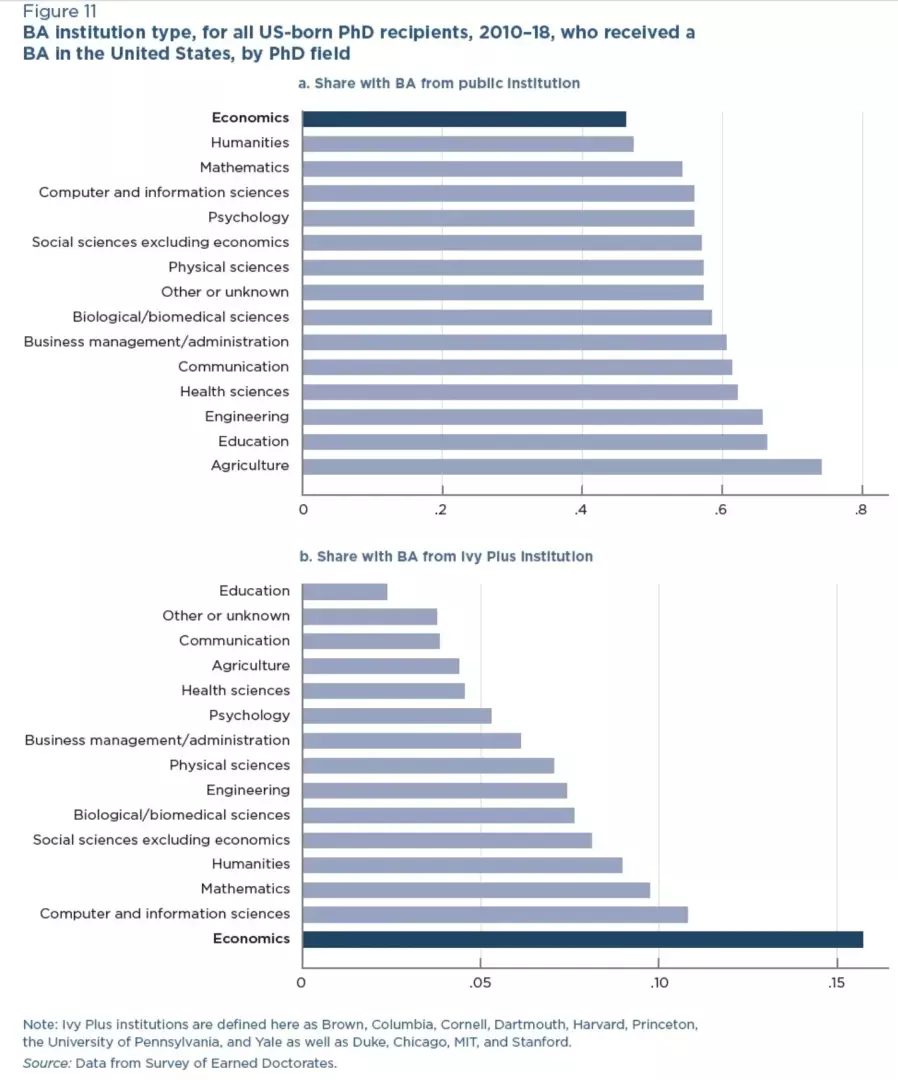

A related insight from Schultz and Stansbury is to look at the share of economics PhDs who graduated from what they call the “Ivy Plus” category–that is, the eight Ivy League schools plus Stanford, MIT, the University of Chicago, and Duke. The focus here is on US-born PhD recipients from all fields. The top panel shows that among US-born PhDs in all field, those in economics are least likely to have received their undergraduate BA from a public institution; the bottom panel shows that among US-born PhDs in all field, those in economics are much more likely to have received their undergraduate BA from one of the “Ivy Plus” institutions. (Moreover, if one included some of the more selective public universities like University of California-Berkeley and Michigan in the “Ivy Plus” category, these gaps would appear wider.)

I won’t try to draw big-picture conclusions here about “what it all means about economics.” But the picture that emerges is that PhD programs in economics seem notably less open to the range of parental backgrounds than other fields. Moreover, that lack of openness is being enforced and replicated by admissions committees in economics PhD programs.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest