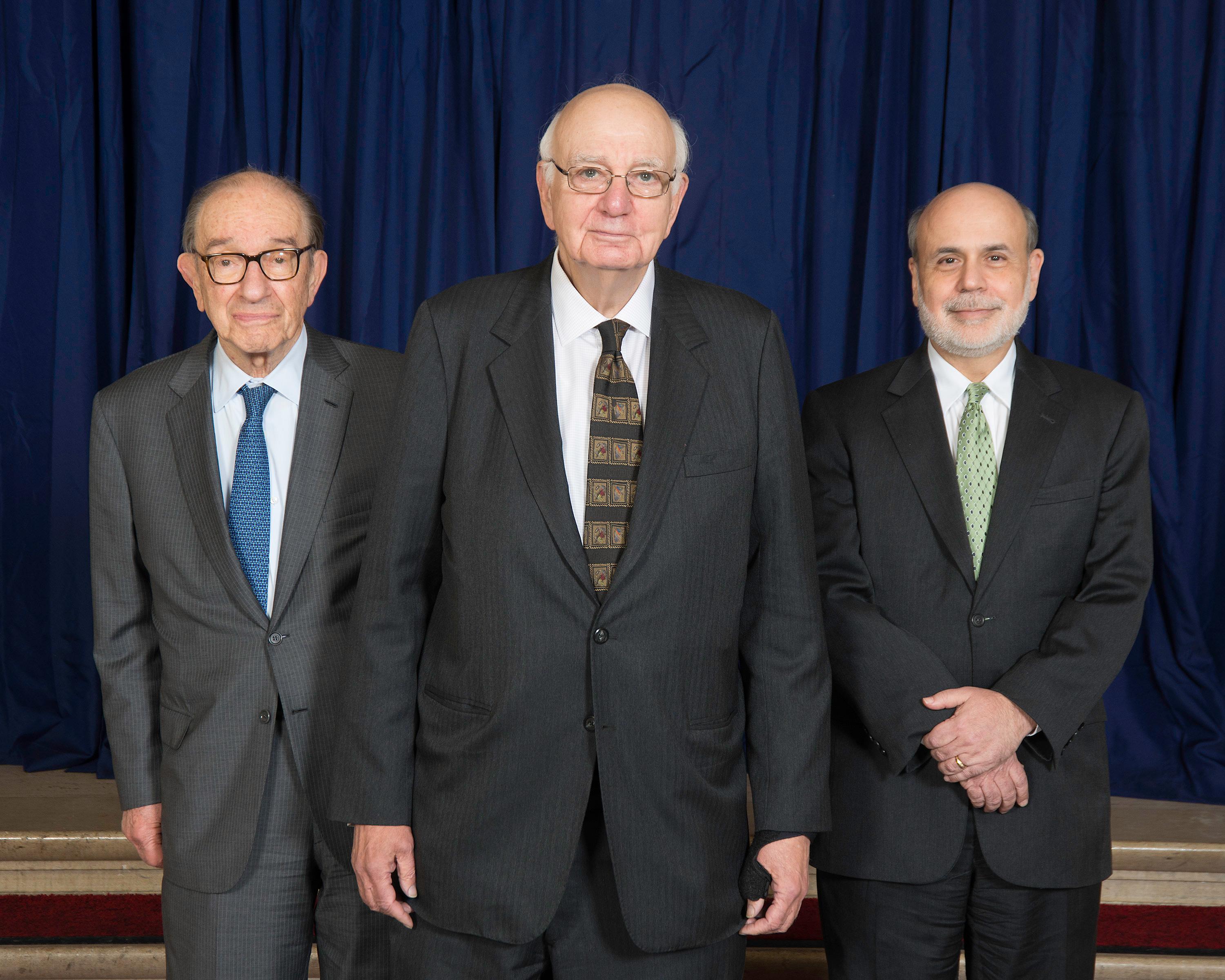

Paul Volcker, who was chair of the Federal Reserve from August 1979 to August 1987 has died. He is generally credited, or in some cases blamed, for the set of monetary policies which both ended the inflationary period of the 1970s but also brought on the very deep double-dip recessions of 1980 and 1981-2. The New York Times obituary is here.

For an overview of those times and how Volcker perceived the choices he was facing, a useful starting point is "An Interview with Paul Volcker," conducted by Martin Feldstein, which appeared in the Fall 2013 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Here's a flavor:

It made a profound impression on me, if nobody else, that Arthur Burns titled his valedictory speech “The Anguish of Central Banking” (Burns 1979). That was a long lament about how, in the economic and political setting of the times, the Federal Reserve, and by extension presumably any central bank, could not exercise enough eserve, and by extension presumably any central bank, could not exercise enough restraint to keep inflation under control. It was a pretty sad story. If you were going to follow that line, you were going to give up, I guess. I didn’t think you could give up. If I was in that job, that was the challenge as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. You inherit a certain challenge ...

The favorite word at the time, which was very popular within the Federal Reserve, but I think popular in the academic community generally, was “gradualism.” I don’t quite remember them saying, “Don’t bring it down at all.”But instead, it was “Take it easy. It will be a job of, I don’t know, years, decades, whatever, and you can do it without hurting the economy.” I never thought that was realistic. The inflationary process itself brought so many dislocations, and stresses and strains that you were going to have a recession sooner or later.

The idea that this was just going to go on indefinitely, and the inflation rate got up to 15 percent, it was going to be 20 percent the next year. One little story (I think of all these stories): Shortly after we began the disinflation, somebody, I think Arthur Levitt who was the head of the American Stock Exchange, brought in some businessmen—they tend to be small businessmen—To talk to me at the Federal Reserve. I had them for lunch, and I gave them my little patter about, “This is going to be tough, but we’re going to stick with it, and the inflation rate is going to come down,” and so forth. The first guy that said, “That’s all very fine, Mr. Volcker, but I just came from a labor negotiation in which I agreed to a 13 percent wage increase for the next three years for the next three years for my employees. I’m very happy with my settlement.” I always wondered whether he was very happy two years later on. But that was symbolic of the depths. He was happy at a 13 percent wage increase.

For context, the US inflation rate as measured by the Consumer Price Index fell from about 13% in 1980 to 3% by 1983.

I'm also reminded of a story that Mervyn King, who for a time chaired the Bank of England, once told about what happens when two of the world's preeminent central bankers try to split a dinner check. King told the story this way:

I first met Paul in 1991 just after I joined the Bank of England. He came to London and asked Marjorie Deane of the Economist magazine to arrange a dinner with the new central banker. The story of that dinner has never been told in public before. We dined in what was then Princess Diana’s favourite restaurant, and at the end of the evening Paul attempted to pay the bill. Paul carried neither cash nor credit cards, but only a cheque book, and a dollar cheque at that. Unfortunately, the restaurant would not accept it. So I paid with a sterling credit card and Paul gave me a US dollar cheque. This suited us both because I had just opened an account at the Bank of England and been asked, rather sniffily, how I intended to open my account. What better response than to say that I would open the account by depositing a cheque from the recently retired Chairman of the Federal Reserve. I basked in this reflected glory for two weeks. Then I received a letter from the Chief Cashier’s office saying that most unfortunately the cheque had bounced. Consternation! It turned out that Paul had forgotten to date the cheque. What to do? Do you really write to a former Chairman pointing out that his cheque had bounced? Do you simply accept the financial loss? After some thought, I hit upon the perfect solution. I dated the cheque myself and returned it to the Bank of England. They accepted it without question. I am hopeful that the statute of limitations is well past. But the episode taught me a lifelong lesson: to be effective, regulation should focus on substance not form.

A version of this article first appeared on Conversable Economist.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest