Comments

- No comments found

A “stablecoin” is a kind of cryptocurrency.

But unlike (say) Bitcoin, the value of a stablecoin is attached to a certain currency–often the US dollar, but in theory some combination of other assets. In other words, no one should be buying stablecoin because they expect its value to rise! By its nature, it can only be used as a store of value or as a means of payment.

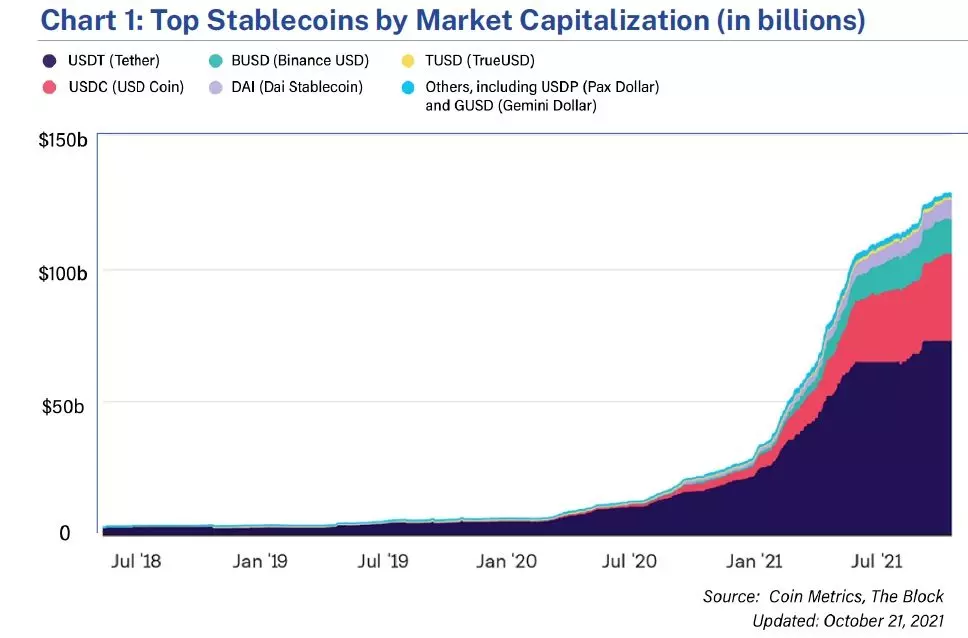

Stablecoin holdings quintuple from October 2020 to October 2021, reaching $127 billion. Thus, the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG), joined by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), released a Report on Stablecoins” in November 2021. Here’s a figure showing the rise in stablecoins, with Tether and USD Coin leading the way.

Why buy stablecoins at all? Imagine that you are someone who wants to buy and sell another blockchain-based cryptocurrency like Bitcoin, or wants to become involved in what is known as “decentralized finance” or DeFi–which the report defines as “a variety of financial products, services, activities, and arrangements supported by smart contract-enabled distributed ledger technology.” In short, you want to live in a blockchain world and avoid dealing in regular currencies like the US dollar, but you also want the fluctuations in value of other cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. Thus, you turn to a blockchain-based stablecoin instead. As the report notes: “At the time of publication of this report, stablecoins are predominantly used in the United States to facilitate trading, lending, and borrowing of other digital assets. For example, stablecoins allow market participants to engage in speculative digital asset trading and to move easily between digital asset platforms and applications, reducing the need for fiat currencies and traditional financial institutions.”

How much should federal financial regulators be worried about stablecoins? As the report points out, there are a number of potential risks. What if the stablecoin is not actually backed with other assets in a way that lets it hold its value? What if payment via stablecoin doesn’t work for reasons ranging from systemic breakdown to honest mistake to fraud?

Because a group of government regulators are writing this report, it is perhaps unsurprising that they recommend a sweeping new set of federal laws to govern stablecoins, with a recommendation that “Congress act promptly to enact legislation to ensure that payment stablecoins and payment stablecoin arrangements are subject to a federal prudential framework on a consistent and comprehensive basis.” This would include steps like: treating all stablecoin companies as insured depository institutions, with standard oversight rules similar to those for banks: regulations for the “digital wallet” companies where people hold their stablecoins for security and financial stability; standard to ensure smooth interoperability between stablecoin platforms; and rules about ownership or affiliation of stablecoin companies with other commercial firms.

But before we try to sweep stablecoins and all other cryptocurrencies under the warm blankets of federal financial regulation, I find myself tempted by more of a “buyer beware” approach. At this stage, the whole idea of blockchain-based payments is in a stage of experimentation. Maybe we should generally let this experimentation play out awhile longer. After all, a government regulatory apparatus offers reassurances that will reduce the risks of stablecoins and other blockchain-related assets–and in this way will tend to encourage use of such assets. It’s not clear to me that it should be an official government policy goal to encourage large chunks of the financial system to migrate to blockchain-related systems.

Right now, in the context of the US financial system as a whole, $127 billion in stablecoins is not a lot. The report notes:

Unlike most stablecoins, the traditional retail non-cash payments systems—that is, check, automated clearing house (ACH), and credit, debit, or prepaid card transactions—all rely on financial institutions for one or more parts of this process, and each financial institution maintains its own ledger of transactions that is compared to ledgers held at other institutions and intermediaries. Together, these systems process over 600 million transactions per day. In 2018, the number of non-cash payments by consumers and businesses reached 174.2 billion, and the value of these payments totaled $97.04 trillion. Risk of fraud or instances of error are governed by state and federal laws …

In addition, if stablecoins or other cryptocurrencies are being used for money-laundering or other illegal transactions, government regulators and law enforcement have shown an ability to break through that anonymity when they have a strong reason to do so. The US Treasury oversees something called the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCen. The stablecoin report notes in its acronym-heavy way:

In the United States, most stablecoins are considered “convertible virtual currency” (CVC) and treated as “value that substitutes for currency” under FinCEN’s regulations. All CVC financial service providers engaged in money transmission, which can include stablecoin administrators and other participants in stablecoin arrangements, must register as money services businesses (MSBs) with FinCEN. As such, they must comply with FinCEN’s regulations, issued pursuant to authority under the BSA [Bank Secrecy Act], which require that MSBs maintain AML [anti money-laundering] programs, report cash transactions of $10,000 or more, file suspicious activity reports (SARs) on certain suspected illegal

activity, and comply with various other obligations. Current BSA regulations require the transfer of certain specific information well beyond what can be inferred from the blockchain resulting in non-compliance. While the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has provided guidance on how the virtual currency industry can build a risk-based sanctions compliance program that includes internal controls like transaction screening and know your customer procedures, there may be some instances where U.S. sanctions compliance requirements (i.e., rejecting transactions) could be difficult to comply with under blockchain protocols.

For now, this kind of financial regulation for stablecoins seems like plenty to me. If you are worried about the other risks of stablecoins and other cryptocurrencies, then you should be figuring out other ways to reduce those risks, not relying on federal regulation to rescue you.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest