Comments

- No comments found

Part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) signed into law by President Trump on March 27, 2020, was a national moratorium on evictions.

However, the moratorium was scheduled to end on July 24, 2020–although it effectively required an additional 30 days beyond that date before landlords could file notices to vacate. Congress did not vote to extend the moratorium. However, the Centers for Disease Control then announced a national eviction moratorium to start on September 4, 2020. The US Supreme Court held in August 2021 that the CDC lacked the power to make this policy decision without the passage of a law through Congress and signed by the president. Of course, the Supreme Court decision was not about whether the eviction moratoriums were good policy or had beneficial effects. Here, I set aside the legal questions and focus on what we know about the outcomes.

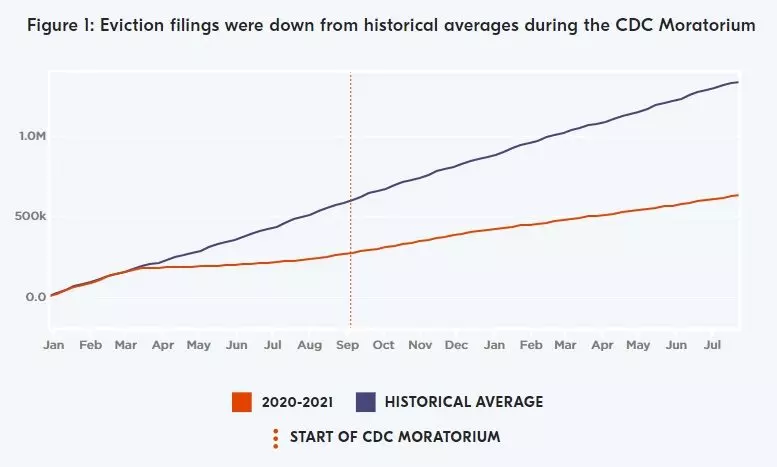

It’s worth saying at the start that data on rental evictions is not nationally centralized, and is not up-to-the-minute. Every study has its own sample. However, certain patterns do seem to emerge across studies. Jasmine Rangel, Jacob Haas, Emily Lemmerman, Joe Fish, and Peter Hepburn at The Eviction Lab at Princeton University provide evidence on overall eviction patterns in “Preliminary Analysis: 11 months of the CDC Moratorium” (August 21, 2021). Their project collects data from 31 cities and six full states, representing about one-fourth of all the renters in the country. Here’s their estimate based on the sites they trask of how the total number of evictions would have evolved starting in January 2020, compared to what actually happened. Evictions fall by about half starting in March 2020 , and the gap between expected and actual evictions continues to expand after the CDC moratorium is enacted in September 2020.

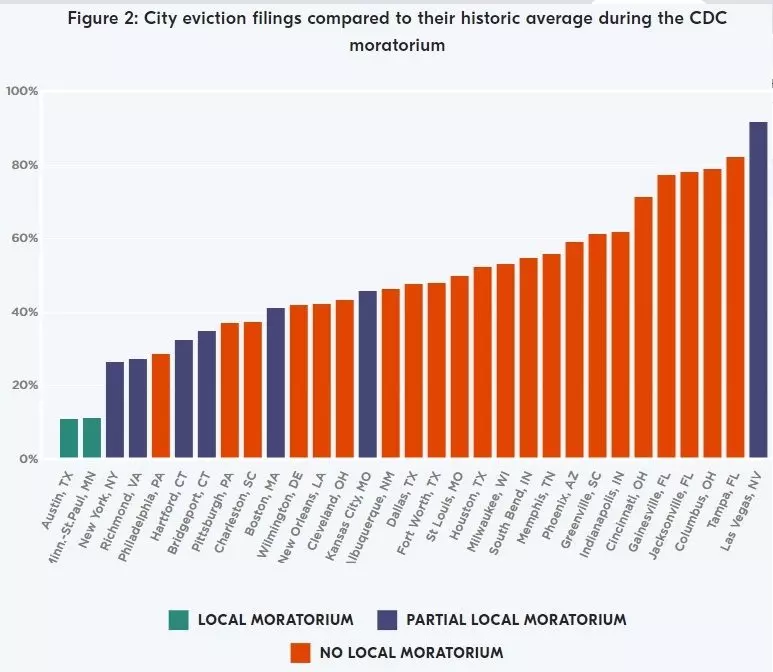

This drop in evictions has considerable local variation, in part because some states and cities enacted new eviction restrictions of their own. For example, here’s a figure showing the pattern across cities.

The researchers at the Eviction Lab also use data on the sites they track, together with historical data from the rest of the country, to make some overall estimates. They write: “In total, we estimate that federal, state, and local policies helped to prevent at least 2.45 million eviction filings since the start of the pandemic (March 15, 2020).” However, as far as I can tell, this estimate assumes that without the moratorium, evictions would have remained at pre-pandemic levels even after the pandemic started, which isn’t obvious. One can imagine that factors other than the moratorium made a difference, too.

What were some of the benefits of the eviction moratorium? The US Department of Housing and Urban Development published a magazine called Evidence Matters, with the Summer 2021 issue devoted to several articles on the theme of “Evictions.” The articles are heavily footnoted with references to published studies. The first article is titled “Affordable Housing, Eviction, and Health.”

The HUD article point out that the most recent national evidence from 2016 suggest that about 8 of every 100 renters got an eviction notice that year. It’s not clear how the number of official eviction notices translates into actual evictions: evidence from some cities suggests that informal evictions are more common than formal ones; evidence from other cities suggests that only about half of eviction notices lead to an actual eviction. Both of these confounding factors can be true, of course. The article notes (footnotes omitted):

Nonpayment of rent is the primary reason for eviction, which itself can arise from various causes, including rising rents combined with stagnant income growth and persistent poverty, job or income loss, or a sudden economic shock such as a health emergency or a car breakdown. Other reasons include lease violations, which can be technical in nature; property damage; and disruptions, such as police calls. Landlords, for their own reasons, may force tenants to move, either informally or through a legal “no-fault” eviction. Renters often are evicted over relatively small amounts of money — in many cases, less than a full month’s rent. … These studies built on the findings of local investigations. The Milwaukee Area Renters Study found higher rates of eviction for African-American, Latinx, and lower-income renters and renters with children. Neighborhood crime and eviction rates, the number of children in a household, and “network disadvantage” — defined by Desmond and Gershenson as “the proportion of one’s strong ties to people who are unemployed, addicted to drugs, in abusive relationships, or who have experienced major, poverty-inducing events (e.g., incarceration, teenage pregnancy) to increase his or her propensity for eviction” — are factors associated with an increased likelihood of eviction.

During the pandemic, some evidence suggests that the eviction moratorium, by keeping households in place, helped to limit the spread of COVID.

Eviction is a particular threat to health during a pandemic because, as Benfer explains, “we know that eviction results in doubling up, in couch surfing, in residing in overcrowded environments, in being forced to use public facilities, and, at the same time, not being able to comply with pandemic mitigation strategies like wearing a mask, cleaning your PPE [personal protective equipment], social distancing, and sheltering in place.” Epidemiological modeling under counterfactual scenarios comparing results with a strict moratorium against results without a moratorium suggests that evictions increase COVID-19 infection rates significantly. …

By studying COVID-19 incidence and mortality in 43 states and the District of Columbia with varying expiration dates for their eviction moratoria, Leifheit et al. found that “COVID-19 incidence was significantly increased in states that lifted their moratoriums starting 10 weeks after lifting, with 1.6 times the incidence…[and] 16 or more weeks after lifting their moratoriums, states had, on average, 2.1 times higher incidence and 5.4 times higher mortality.” The researchers conclude that, nationally, expiring eviction moratoria are associated with a total of 433,700 excess COVID-19 cases and 10,700 excess deaths. Another study estimates that, had eviction moratoria been implemented nationwide from March 2020 through November 2020, COVID-19 infection rates would have been reduced by 14.2 percent and COVID-19 deaths would have been reduced by 40.7 percent.

A certain amount of the literature on the eviction moratorium focuses so intensely on the outcomes for renters that it barely mentions landlords, although when it comes to understanding rental markets, this is like discussing the yin without the yang. But there are some exceptions. Elijah de la Campa, Vincent J. Reina and Christopher Herbert published “How Are Landlords Faring During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Evidence from a National Cross-Site Survey” (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, August 2021), based on a national survey of landlords carried out from February to May 2021. The research group at JP Morgan Chase recently published “How did landlords fare during COVID?” (October 2021), which is based on Chase customers who are small business owners and who have indicates that they own a residential property that is rented out, or customers who have a mortgage from Chase on a multifamily or investment property. Both sources of data have their limitations, as noted above. But some overall patterns do emerge.

The studies both find that many landlords experienced real disruptions of income during the pandemic. The Harvard study found: “The share of landlords collecting 90 percent or more of yearly rent fell 30 percent from 2019 to 2020. … Ten percent of all landlords collected less than half of their yearly rent in 2020, with smaller landlords (1-5 units) most likely to have tenants deeply behind on rental payments.” The JP Morgan Chase study finds that “in the spring of 2020 … rental revenue for the median landlord was down about 20 percent relative to 2019.”

On the other side, for many landlords the eviction moratorium wasn’t as bad as it might have been. Many renters were receiving substantial payments from the government, and some of those flowed through to landlords. Some landlords who had mortgages on their rental properties were able to take advantage of policies to push back those payments for a time. Both the Harvard and the JP Morgan Chase studies find that many landlords also reduced or postponed their spending on maintenance. Others put their rental properties up for sale. The Harvard survey found: “The share of landlords deferring maintenance and listing their properties for sale also increased in 2020 (5 to 31 percent and 3 to 13 percent, respectively)…”

The federal government did allocate funds to help renters, and thus landlords, but that particular problem never really got off the ground. The JPMorgan study puts it this way (again, footnotes omitted):

Between the Emergency Rental Assistance Program and the American Rescue Plan Act, $46.5 billion of rental assistance has been made available by the federal government for states and localities to distribute. As of the end of September [2021], less than a quarter of the funds have been distributed. The distribution of these funds has been hampered by onerous paperwork requirements for both tenants and landlords to prove that tenants meet strict requirements to qualify for assistance, including matching information from the renter and the landlord. Among the many challenges, many of the most vulnerable tenants are not part of the formal rental market (e.g., subletting, renting illegal units, striking informal agreements, etc.) and are not able to provide the leases or other paperwork that is required of them to receive aid. Government officials have altered the rules of the program over time (e.g., allowing for self-attestation of need, providing advances while paperwork is processed, increasing flexibility for what the funds can be used for, etc.) to accelerate the process for getting assistance to needy families when it became clear that paperwork had become too much of a bottleneck. Such flexibility will be key to helping landlords as the pandemic drags on and keeping tenants in their homes as the expiration of various eviction moratoriums rapidly approaches. This need is especially acute for smaller landlords as they are more likely to supply affordable rental housing and rent shortfalls during the pandemic has caused more of them to sell their rental properties. Helping these landlords helps to preserve our supply of affordable housing.

Renters tend to haver lower income than landlords, and renters suffered more in financial terms during the pandemic than landlords. But given that the US rental housing markets are fundamentally based on private-sector rentals, the ability and willingness of landlords to be provide affordable rental housing in the future is important .

The issue of what rules should govern rental evictions existed before the pandemic, and will be a perennial topic moving ahead as well. Whatever the case for a national moratorium as a short-term or even a medium-term step, it surely can’t be a permanent policy. The HUD publication goes into these issues and discusses various local programs, although I don’t have a strong sense of what localities have rules that work better or worse. The HUD also offer some interesting evidence that evictions tend to be highly concentrated in certain areas and even among certain landlords in those areas. As the report notes: “Among the implications of these findings is that interventions targeted at the neighborhoods, buildings, and landlords responsible for significant numbers of evictions can have a profound impact.”

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest