Comments

- No comments found

Men and women tend to sort into different college majors. Even given the same college major, they tend to sort into different jobs.

Carolyn M. Sloane, Erik G. Hurst, and Dan A. Black explore these patterns, and some implications for wage differences between men and women, in “College Majors, Occupations, and the Gender Wage Gap” (Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2021, 35:4, pp, 223-48).

(Full disclosure: I’ve been the Managing Editor at JEP since the first issue in 1987, so I am perhaps predisposed to think the articles are of wider interest. Fuller disclosure: All JEP articles back to the first issue have been freely available online for a decade now, courtesy of the American Economic Association, so neither I nor anyone else get any direct financial benefit if you choose to check out the journal.)

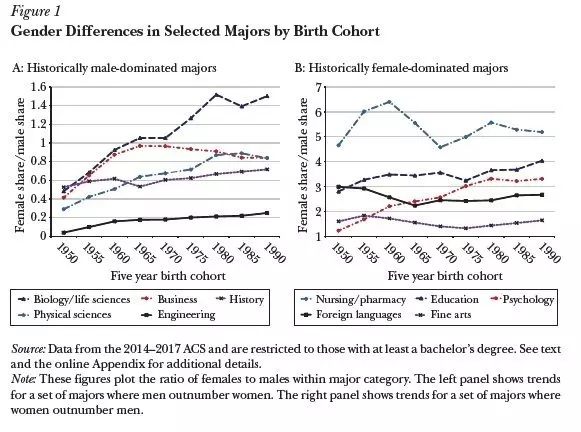

For example, here are some broad groupings of majors that tend to be male- or female-dominated. The left-hand panel shows majors where the female/male share of majors started at less than 1. Biological sciences has risen above one, and is now majority female, but the other majors have changed much less. The right-hand panel shows broad categories majors where the female/male share of majors started above one–in some cases, several multiples above one. None of these areas have switched to majority male: in one area, psychology, the female dominance has become much more pronounced.

Sloane, Hurst, and Black aren’t trying to explain why these patterns arose or why they persist (although that’s an obvious topic for speculation!). Instead, they are interested in pointing out the extent of this difference, its persistence over time, and pointing out that the male-dominated majors on average have higher wages. Their data breaks down the broad major categories into 134 detailed majors: for example, the category of “Engineering” contains 17 different majors. They write:

We find that women are systematically sorted into majors with lower potential wages relative to men. For example, Aerospace Engineering, one of the highest potential wage majors, is 88 percent male, while Early Childhood Education, one of the lowest potential wage majors, is 97 percent female. We also find that such patterns are long-standing and have been slow to converge. Overall, college-educated women born in the 1950s matriculated with majors that had potential wages 12 percent lower than men from their cohort. That gap fell to about 9 percent for the 1990 birth cohort. Even after some convergence in major sorting between men and women during the last 40 years, the youngest birth cohorts of women are still sorted into majors with lower potential wages than their male peers. Intriguingly, much of the convergence in major sorting between men and women occurred between the 1950 and 1975 birth cohorts, with a modest divergence for recent cohorts.

The authors use an interesting method of comparing wages across majors. For every major, they look at the median wages paid to a middle-aged, US-born, white male in that category. Thus, they are not trying to measure gaps between female and male wages, or the extent of discrimination. Instead, they are noting that wages are lower in female-dominated majors even if one just compares white men of the same age with different majors.

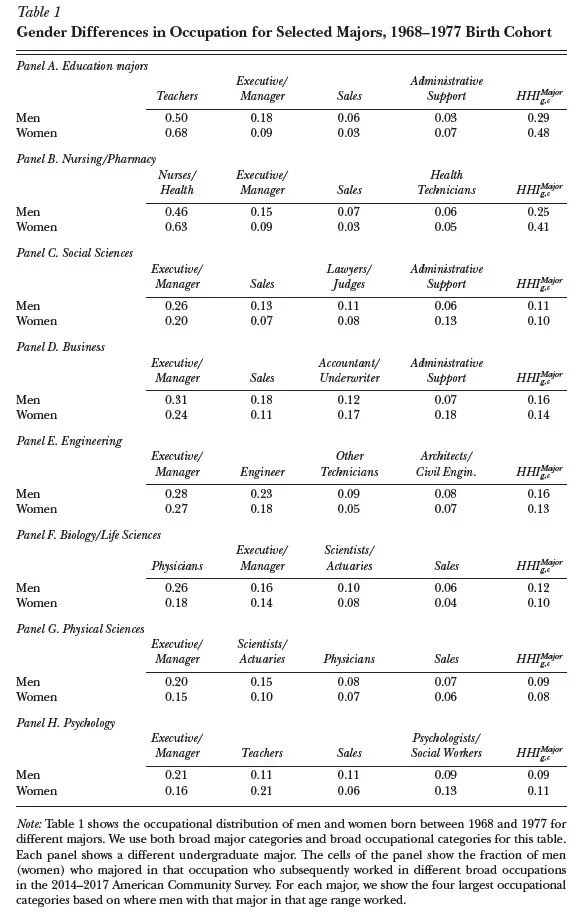

They then take the idea of sorting one step further. Men and women who have the same major tend to sort into different occupations. Here’s a table illustrating this pattern. The top category shows that for education majors, 68% of women end up as teachers, compared with 50% of men. But among education majors, 18% of men end up in executive/manager jobs, compared with 9% of women. Similarly, the next panel shows that among nursing/pharmacy majors, women are more likely to end up as nurses, while men are more likely to end up in executive/manager roles.

{H]ow has occupational sorting conditional on major evolved across generations of US college graduates? We find that while women are sorted into occupations with lower potential wages conditional on major, this gap is closing somewhat over time. For the 1950 birth cohort, for example, women on average sorted to occupations with 11 percent lower potential earnings relative to otherwise similar men with the same majors. This gap narrowed to about 9 percent for the 1990 birth cohort. Almost all of the convergence occurred within highest potential earning majors. For example, women from the 1950 cohort who majored in Engineering—a high potential earning major—sorted into occupations with potential wages that were 14 percent lower than men from the same cohort who also majored in Engineering. For the 1990 birth cohort, however, women who majored in Engineering ended up working in occupations with roughly the same potential wages as their male peers.The authors have data on 251 distinct occupations. They find that when women and men have the same majors, women have historically sorted into lower-paid occupations (again, just noting that this happens, while not investigating the question of how or why). For the effect of this occupational sorting for men and women with the same college major, they write:

Of course, these patterns of sorting by college major and occupation are also taking place against a backdrop of other changes: a rising share of women graduating from college, expansion of the US health care sector, falling birth rates, and so on. But the importance of sorting that happens early in life in college major and occupation has a lasting importance to later wages. The authors find that accounting for sorting by college major, and by occupation given the same major, can explain about 60% of the wage gap between men and women college graduates.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest