There's one event that very often turns college enrollment into a poor financial decision with a negative payoff: not completing a degree. Then that happens, the student has spent both money and some years of time in a program that not only offers little financial payoff, but may also leave them saddled with student loans to repay for years to come. More broadly, society's investment in higher education isn't paying off. Two DC think-tanks, ThirdWay and the American Enterprise Institute, have published a set of five readable papers on the subject:

Bridget Terry Long offers a nice overview of the problem she writes:

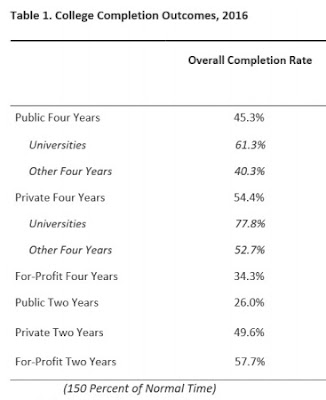

"The conventional way to measure graduation rates is to examine how many students complete a degree within 150 percent of the expected completion time—that is, six years for a bachelor’s degree and three years for an associate degree. Using this metric, research suggests that about only half of students enrolled at four-year colleges and universities graduate within 150 percent of the expected completion time, and the completion rate is even lower for students enrolled at two-year colleges."

Here's a table from her paper showing college completion rates across different types of institujtions by this measure.

Sarah Turner's essay offers some additional in-depth background. On the horizontal axis, these graphs show spending per student. On the vertical axis, they show completion rates (again, as measured by completing a degree within 150% of the expected time) Each dot is a college or university. The central insight is that there is a very wide range of completion rates across schools in the same category that spend much the same amount per student.

Turner writes:

"In 43 four-year public schools, the three-year cohort default rate is greater than the completion rate. This is also the case for 147 four-year private nonprofit schools and 98 for-profit schools. In other words, students in these schools who borrow face a greater likelihood of defaulting than completing a degree. It would seem, then, that college attendance at these schools leaves many students worse off—lacking a degree, defaulting on a student loan, or both."

The papers tend to be stronger on describing the problem than on providing clearly workable solutions, but that's the nature of this issue. College completion rates have been low for a long time, but with the cost of college now having climbed so very high, the issue has a new relevance. For example, Destin looks at how improvements in the psychological environment at a school, including elements of teaching and campus life, can help. Chingos emphasizes that students need preparation to be ready to do college-level work. Turner discusses the pros and cons of linking college completion rates and the levels of state support and financial aid. Schneider and Clark summarize reforms that have improve completion rates at certain schools.

One challenge here is to remember that the ultimate goal isn't to punish schools with low completion rates (although that may be necessary in some cases). It's to have fewer students falling off the path to college completion.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest