Comments

- No comments found

Being more attractive is associated with having a higher income.

What one chooses to make of this fact can be a source of controversy. But the fact itself is well-established. Ellis P. Monk Jr., Michael H. Esposito, and Hedwig Lee discuss the topic in “Beholding Inequality: Race, Gender, and Returns to Physical Attractiveness in the United States” (American Journal of Sociology, July 2021). For example, they describe some of the earlier research in this way (citations omitted):

While a one-standard-deviation increase in ability is associated with 3%–6% higher wages, attractive or very attractive individuals earn 5%–10% more than average-looking individuals. Another study even finds that returns to perceived attractiveness unfold over the life course and are robust to a wide array of potentially relevant controls, such as educational attainment, parental background, personality traits, IQ, and so on.

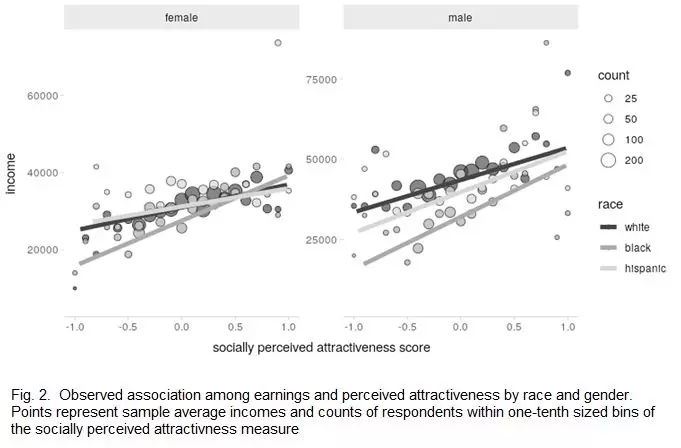

Of course, some obvious questions in this line of research include who is deciding what is “attractive,” and whether “attractive” is primarily a marker for other categories like race/ethnicity or gender. For example, if one compares within the category of, say, black women, is there still a positive association between attractiveness and income? How is the benefit of attractiveness distributed across groups, and it is larger for some groups than others? The authors describe their results in this way (references to figures omitted):

[W]e must emphasize, however, that perceived physical attractiveness is a major factor of inequality and stratification regardless of one’s race or gender. In fact, our analyses suggest that the magnitude of the earnings gap among White men along the perceived attractiveness continuum rivals that of the canonical Black-White wage gap and the attractiveness earnings gap among White women actually exceeds, in real dollars, the Black-White wage gap.

This, however, is not at all to say that race and gender do not matter. Quite the contrary. We find that while the returns to perceived physical attractiveness are similar for most race-by-gender combinations, the slope of the returns to perceived physical attractiveness is steepest among Black women and Black men. The returns to attractiveness among Black women, for instance, are so immense, that the earnings of the most attractive Black women appear to converge or even overlap those of white women of similar levels of attractiveness. Notably, the returns to perceived physical attractiveness, in terms of real dollars, are similar between White males and Black females even though Black females make significantly less than White males on average. Similarly, the returns to attractiveness among Black men are quite substantial as well, though not enough to see a convergence or cross-over with white men. Among Black women and Black men, the wage penalties associated with perceived physical attractiveness are also so substantial that, taken together, the earnings disparity between the least and most physically attractive exceeds in magnitude both the Black-White wage gap and the gender gap.

Here’s a figure to illustrate some of the results. The horizontal axis is a measure of attractiveness. The vertical axis measures income. The lines on the graph are three shades of gray: the darkest line is the white population, the in-between gray is the black population, and the lightest shade of gray is the Hispanic population. For all groups the lines slope up: that is, those who are more attractive have higher income. But the slope of the “attractiveness” line is especially steep for black women and men.

An obvious question in this kind of research is what data was used, and how “attractiveness” was defined. The data is from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, which is “an ongoing, nationally representative survey of a group of individuals who were in grades 7–12 in 1994.” The original sample included more than 20,000 individuals from 132 schools across the country, and the survey was an in-depth home interview. There were four waves of surveys, in 1994-95, 1996, 2001-2, and 2007-8. They focus on the 9300 people who were in all four waves.

The survey asked the interviewers to evaluate the physical attractiveness of the respondent, but did not give them any guidelines for doing so. However, one can compare attractiveness rankings given by male and female interviewers, and across black and white interviewers. The short answer to these questions is that while it is hard to define “attractive,” people tend to know it when they see it. The authors write:

Overall, then, there seems to be overwhelming consensus on ratings of attractiveness across interviewers regardless of race/ethnicity and gender. Furthermore, our analyses reveal virtually no evidence of same-race bias in their attractiveness ratings. Thus, taken together, even though these measures are subjective and there is some variation, interviewers exhibit consensus, which is in line with the findings of research on judgments of attractiveness …

One can hypothesize about the possible reasons for a link between attractiveness and income. For example, perhaps attractiveness is more likely to get certain people hired or promoted, even if those people have otherwise identical skills. Alternatively, perhaps attractive people are more likely to have better skills when entering the workplace, perhaps because when they were younger or going through school their attractiveness meant that they got more attention and support. Or perhaps being “attractive” is in part the result of a set of soft social skills and behaviors–say, ability to notice and follow social cues about what attractiveness means, together with disciplined patterns of diet, exercise, and other personal habits–which are correlated with skill-sets that are desired in the workplace. Or perhaps the bias arises in part because potential customers in certain industries are more likely to give their eyeballs or their spending power, or both, to more attractive people.

The authors do not discuss the topic of how society might respond to attractiveness bias, and I will follow their example and sidestep the subject here. But at a personal level, it is worth being aware that when you are responding to other people–whether as a co-worker, a customer, a manager, a loan officer, or just someone you walk past on the street–it is likely for most of us that attractiveness bias is shaping our responses.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest