Comments

- No comments found

The US pharmaceutical industry faces two important goals–which conflict with each other.

One goal is to provide needed drugs at the lowest possible price. The other is to provide incentives for research and development of new drugs, which requires some form of compensation for the risks of undertaking such efforts. The US patent system allows inventors to have a temporary monopoly on their discovery, so that they can charge higher prices for a time. After the patent expires, it then becomes legal for others to produce generic equivalents. The result is a two-part market for US pharmaceuticals: expensive drugs still under patent and inexpensive generic drugs.

William S. Comanor layout some of the patters in his essay, “Why Are (Some) U.S. Drug Prices So High?” which is subtitled, “The Hatch–Waxman Act promotes both pharmaceutical innovation and price competition, confounding simple comparisons of U.S. and foreign drug prices” (Regulation, Winter 2021/2022).

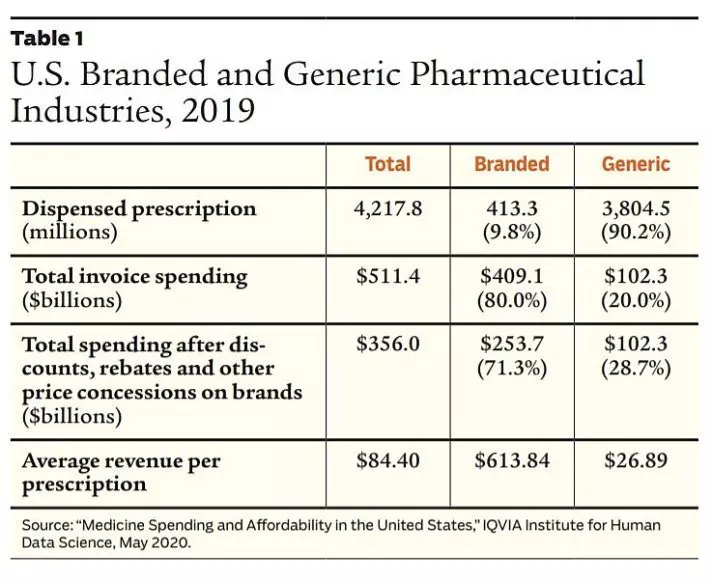

Here’s a table showing how the US pharmaceutical industry has evolved. Notice that about 90% of dispensed prescriptions are generics, accounting for about 20% of total invoice spending, while 10% of prescriptions are branded drugs, accounting for 80% of invoice spending.

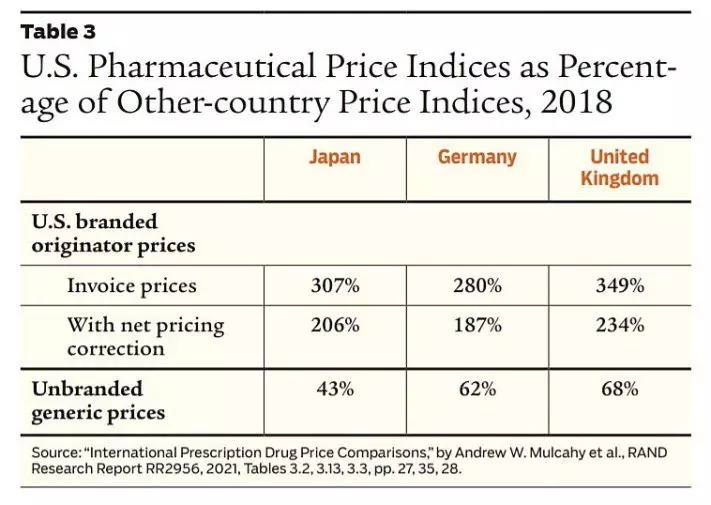

A common complaint about the US pharma industry is that brand-name drugs sell for more in the United States than in other countries, which often impose price controls and other rules on drugs from US firms. What is less-heard is that prices for generic drugs are typically lower in the United States. Here’s a comparison from Comanor. When adjusted for manufacturer discounts (“net pricing correction”), branded drugs cost about twice as much in the US as in Japan, Germany, and the UK. However, generic drugs in the US cost about one-third less than Germany and the UK, and less than half as much as in Japan.

The bifurcated US approach to pharmaceuticals has led to global dominance of US drug companies. Comanor reports:

As disclosed in the RAND report, the United States accounts for 58% of total pharmaceutical sales revenue among nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, whereas the second and third highest counties, Japan and Germany, are 9% and 5% respectively. Moreover, because U.S. branded prices are higher than elsewhere, the United States accounts for approximately 78% of worldwide industry profits. All other countries, in aggregate, account for less than one-third of that amount. Put simply, U.S. profits incentivize global innovation.

Of course, one can imagine a variety of potentially useful ways to tweak the patent rules or the rules for drug regulation. It also seems to me that the goal of profit-seeking drug companies is to develop expensive drugs for extreme conditions that will generate high profits, along with in-demand drugs for conditions like hair loss. There’s an important rule here for government support of R&D to encourage innovating in a ways that the market might not reward very well: for example, a focus on the important but neglected health conditions; a focus on “orphan drugs” for health problems that affect only a few people and might not be very profitable; and a focus on versions of drugs with lower costs or fewer side effects. It would also be nice if the rest of the world would step up and pay a bigger part of the bill for developing new drugs, too. But in some broad sense, the bifurcated US drug market–an outcome of the Hatch-Waxman act passed back in 1984–has actually worked out pretty well.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest