Comments (4)

Paula Brazier

Twitter has confirmed that workers can work from home forever

Tracey Evans

We are heading towards a remote economy

Ash Coburn

Goodbye face to face interactions

Laura Malkin

Good read

Responses to the pandemic have shifted many patterns: online education for both K-12 and higher ed, online health care consultations, online business meetings, and telecommuting to jobs.

It will be interesting to see whether these shifts are only temporary, or whether they are the first step to a more permanent shift. Here are some bits and pieces of evidence.

The word "telecommuting" and the emergence of the idea into public discourse happened in the early 1970s. A NASA engineer named Jack Nilles, who in fact was working remotely, is usually credited with coining the word. He was also the lead author on a 1973 book looking more closely at the idea:

The Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff: Options for Tomorrow.

Before the pandemic, the share of US workers who telecommuted on a regular basis had been creeping up rather slowly over time, and had exceeded 5% of the workforce. From one perspective, this isn't a huge number. From another perspective, it suggest that a lot of workers and employers have some experience with telecommuting over time. And for the country as a whole, the number of telecommuters already exceeded the number taking mass transit on a regular basis.

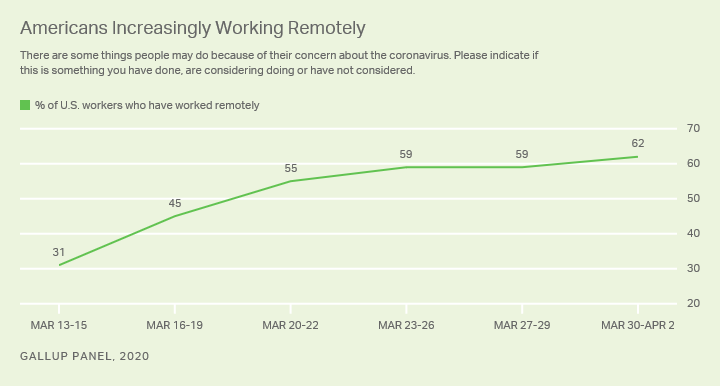

Of course, the pandemic changed telecommuting, along with so much else. A Gallup poll found that in the last two weeks of March 2020, the share of US workers who had ever worked remotely doubled:

There's anecdotal evidence suggesting that for big companies, the shift to telecommuting may be substantial and lasting. For example, a New York Times story suggests "Manhattan Faces a Reckoning if Working From Home Becomes the Norm" (by Matthew Haag, May 12, 2020). The article points out that just three companies--Barclays, JP Morgan Chase and Morgan Stanley--employ more than 20,000 employees in Manhattan and "they lease more than 10 million square feet in New York — roughly all the office space in downtown Nashville."

Before the coronavirus crisis, three of New York City’s largest commercial tenants — Barclays, JP Morgan Chase and Morgan Stanley — had tens of thousands of workers in towers across Manhattan. Now, as the city wrestles with when and how to reopen, executives at all three firms have decided that it is highly unlikely that all their workers will ever return to those buildings. The research firm Nielsen has arrived at a similar conclusion. Even after the crisis has passed, its 3,000 workers in the city will no longer need to be in the office full-time and can instead work from home most of the week.

Manhattan has the largest business district in the country, and its office towers have long been a symbol of the city’s global dominance. With hundreds of thousands of office workers, the commercial tenants have given rise to a vast ecosystem, from public transit to restaurants to shops. They have also funneled huge amounts of taxes into state and city coffers. But now, as the pandemic eases its grip, ... they are now wondering whether it’s worth continuing to spend as much money on Manhattan’s exorbitant commercial rents. They are also mindful that public health considerations might make the packed workplaces of the recent past less viable. ...

Lots of other prominent firms, like Twitter and Facebook, are also announcing that work-from-home will be available to many more employees in the future.

With just a bit of imagination, one can envisage a future where corporate offices have a lot less floorspace. There would be rooms for team meetings, and a number of cubicles or small offices that would be used by whoever was physically present that day. But the idea that most workers have a desk or cubicle or office reserved or them would fad away. One can also imagine a corresponding shift on the residential side of the market. There might be less demand for living near concentrations of urban jobs, and more demand for living near what has been viewed as a vacation destination. (For example, interest in real estate near Lake Tahoe has perked up.) When it comes to choosing a home, more people might go beyond just counting bedrooms and bathrooms and what the countertops are made of, and also looking for a place what has that have a nook or a room designed as at-home workspace.

But what actual evidence bears on the likelihood that such a shift will occur? I'm only aware of one previous example of a relatively shock that led to a very large short-run increase in telecommuting: an earthquake in New Zealand in 2011. Erin Brown explains in an article in Knowable magazine ("Could Covid-19 usher in a new era of working from home?"April 30, 2020).

When a magnitude 6.3 earthquake struck Christchurch, New Zealand, on February 22, 2011, the capital city’s central business district was leveled — and hundreds of essential government workers suddenly found themselves working from home, scrambling to figure out how to get their jobs done without access to the office. Some encountered technical difficulties, others had trouble managing teams. But most found the pros outweighed the cons, and agencies held on to remote work options.

“It was immediate telework,” says Kate Lister, president of Global Workplace Analytics, a consulting firm near San Diego that helps companies set up work-from-home polices. And once it was over, they did not go back.”

On the other side, Brown also points out that not all past experiences with telecommuting have been positive, either from the employer or the employee's point of view. Yahoo! and Best Buy both had work at home policies that they abolished in 2013. More recently, before the pandemic the Trump administration had been reducing telework options for federal employees. Brown writes:

A 2017 look at research on alternative work arrangements, including remote work, in the Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior identified similar benefits. It also documented challenges for remote workers, including feeling lonely, isolated or not respected by colleagues; an increase in work-family conflict due to longer hours and blurred boundaries; and, in some cases, a tendency among workers who are encouraged to maintain work-life boundaries to “be less likely to extend themselves in crunch times, possibly increasing the workload of non-telecommuting coworkers.”

Katherine Guyot and Isabel V. Sawhill offer an essay with links to much of the recent evidence in "Telecommuting will likely continue long after the pandemic" (Brookings Institution, April 6, 2020). They write:

[A] recent paper estimates that only a third of jobs can be done entirely from home. ... Already, nearly one in five chief financial officers surveyed last week said they planned to keep at least 20% of their workforce working remotely to cut costs. ... Cutting commuting is good both for environmental reasons and because it is one of the least enjoyable activities that many adults engage in on a daily basis. ...

It can be a problem when some members of an organization or a team can telework and others cannot. Having more coworkers who telework can result in lower performance, higher absenteeism, and higher turnover among those who do not telework, particularly if team members have very limited face-to-face time. This suggests that telework may create some additional work for onsite workers (for instance, if they have to serve as liaisons for their teleworking colleagues), or that social interaction at work is important for morale. ...

A new study of employees at a U.S. technology services company found that extensive telecommuting is associated with fewer promotions and lower salary growth, but that telecommuters who have face-to-face time with managers or who perform supplemental work outside of normal hours have better outcomes. Supplemental work signals dedication to the job but also blurs the boundary between work and home life, contributing to pressure to be “always on.”

Of course, extrapolating from a pandemic back to (relative) normality is a dicey business. It's plausible that the enormous advances in telecommunications technology would have led to a gradual increase in telecommuting over time. Maybe it will turn out that the pandemic just gave telecommuting a push to move a little faster in the direction it was already headed. Here, I'll just finish with a few thoughts that are dubious about whether a seismic shift in telecommuting has just occurred.

1) For many high-income workers, the option to telework can feel like a way to get some focused work time and also to improve the work-life balance. But if telework is imposed by the employer, and begins to include an expectation of being available for work 24/7, and perhaps especially if it is imposed on low-income workers, the feeling may be quite different. More generally, there may be some workers who are happier heading off to work in an office, with a separation between work and home life.

2) In the pandemic, firms moved people with existing and well-defined jobs into telecommuting for a time. But firms need to evolve over time. Job responsibilities and jobs themselves change. How will hiring and training of new employees happen? How will team-based projects be pursued? How will new directions for the company be conveyed to teleworking employees? How will work be evaluated? The loyalty that workers feel to their employer as unemployment soars in a pandemic may be rather different than the loyalty they feel after working at home for months or years.

3) One of the fundamental questions of urban economics is why economic activity tends to be clumped together in metro areas, and often clumped together in certain parts of urban areas, rather than being spread out more evenly across the landscape. The broad answer is that there are "economies of agglomeration," which is a fancy way for saying that workers who are physically located near each other tend to be more productive, as they share ideas and goals and motivate and interact with each other. There is a large body of empirical evidence on the concentration of economic activity, as well as high productivity and innovation, within specific locations. My suspicion is that the wise and career-oriented telecommuter will still want to find a way to make regular in-person appearances at these locations.

A version of this article first appeared on Conversable Economist.

Twitter has confirmed that workers can work from home forever

We are heading towards a remote economy

Goodbye face to face interactions

Good read

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest