I am privileged to serve as a (uncompensated) science advisor to a young company named InsideTracker, positioned in the vanguard of the “personalized medicine” movement. With some help from my friends at the company (special thanks to Gil Blander, PhD), here’s an introductory overview.

But before getting to those particulars, a brief, contextual preamble. Two powerful currents in modern culture- the advent of healthcare consumerism, and the intense focus on customization in the digital age- are creating an irresistible vortex in the health and wellness domain. There is intense demand for highly personalized approaches to health promotion, and the inevitable supply-side responses. The high-profile allocation of $30million by Campbell’s to fund the nutrigenomic company, Habit, is illustrative. The era of personalized medicine is well established.

Or, at least, the marketing collateral would have it so. The reality is rather different. As so often happens when demand and profits beckon, marketing has gotten far out ahead of the science. While nutrigenomics has considerable market cache, the most definitive recent study of the matter, called DIETFITS, found that genetic markers could not predict responses to specific dietary assignments. Good diets were generally good for health, and genomic profiling did nothing to change that view from altitude.

But this doesn’t mean personalization lacks promise; it simply means that to date, false promises have prevailed over real ones. Nothing personal- that’s just how it is.

There could yet be a genie in the bottle, but if so, the putative magic of personalization requires looking beyond just genes. There are many aspects of personal health to measure- from biomarkers to behaviors. A clear view of the power to personalize may require peering deep inside many nooks and crannies of human physiology, and then compiling those dots into a cogent, holistic picture. In other words, at present, we should be spending a lot of time looking around asking questions- and develop answers cautiously, humbly, and empirically based on what we see. That is the mission InsideTracker has been advancing for the better part of their first, developmental decade.

With a bit of blood and information from you, InsideTracker starts to assemble a composite picture of a comprehensive individual health profile. With information from thousands of participants, there is a unique opportunity to see how dots connect not just in one of us, but also in general, and then apply those insights in the next iteration of health tips. By mining the data of thousands of users who vary by age, gender, ethnic backgrounds, behaviors, preferences, and fitness levels, InsideTracker is able to explore health connections that at times affirm, and at times challenge common beliefs about what’s healthy and what’s not.

Takeout or Restaurant Meals

Everyone’s heard it before: if you want to keep healthy and trim, dine in, not out. This holds true for a myriad of obvious reasons, ranging from portion and ingredient control, to one’s environment and psychological state while consuming food. But, just how far-reaching is the effect of takeout food on a generally healthy person’s biomarkers?

When people identified themselves as consumers of takeout or restaurant meals at least once per day, compared to people who said they rarely or never do, the usual biomarker suspects were significantly affected: Glucose, inflammation and liver enzyme levels were higher, as were levels of “bad” cholesterol (LDL), triglycerides and of course, BMI. Their InnerAge™ – aka biological age – was also on average about 2 years older than their non-takeout scarfing peers.

What the average person may not consider, though, is the fact that frequently consuming takeout or restaurant food actually lowers some biomarker levels, too… just not in a good way. Compared to people who never or rarely consume takeout, those who did so regularly, had lower levels of vitamin D, vitamin B12, folate, and even HDL, the “good” cholesterol. Less is not always more, when it comes to these mighty markers. Low levels of B12 can contribute to exhaustion and poor cognition, while low folate is a risk factor for pregnant women and those looking to conceive; vitamin D is something nearly everyone wants more of in the winter months, and contrary to popular belief, you do want more cholesterol when it comes to HDL.

Alcohol Use (Drinks per Week)

The knowledge that drinking alcohol detrimentally affects the body is about as common as things come. But there are still surprises to be found when it comes to how regular consumption of alcohol affects biomarkers. When InsideTracker compared users who identified as drinking less than one alcoholic beverage per week, to those who said they drink 7 or more per week, they confirmed that the usual suspects were affected – elevated glucose, elevated liver enzymes (GGT), higher triglycerides, higher total and LDL (bad) cholesterol – but there was one interesting surprise. HDL, or “good” cholesterol, levels were lower in those people who did not regularly consume alcohol. Higher HDL (within an appropriate threshold) is healthier. Interestingly, users who said they drink 7 or more alcoholic beverages per week had HDL levels about 5 points higher than their non-drinking counterparts. Current research indicates that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with elevated HDL levels, which is in turn linked to lower incidence of cardiovascular disease. While the reasons for the connection to an increase in HDL are not yet well-studied, the evidence for a correlation exists nonetheless. It is important to keep in mind, however, that moderate alcohol consumption is linked to more negative effects overall on biomarkers than positive ones... so, don't take this as a daily free drink ticket!

Multivitamin Supplementation

If you ask the average person whether they think a multivitamin is beneficial to them, the answer is most likely to be yes (whether they take one or not). This speaks to the power of marketing: for decades, we’ve seen ads, commercials and everyone from actors to athletes hawking the broad-spectrum benefits of multivitamin supplements… to the point where we begin to take their claims as scientific fact. The truth is, there’s plenty of science disproving the broad claims of supplement manufacturers.

When comparing users who identified as taking a multivitamin to those who said they did not, some of their biomarker levels were improved – specifically vitamins D, B12, and folate. However, those same multivitamin takers had higher liver enzyme levels (GGT, ALT and AST), suggesting that the liver has to work harder to detoxify the supplement, and higher BMIs than the people who indicated they did not take multivitamins. One hypothesis as to why this is, is that people who rely on multivitamins may be using supplementation to compensate for suboptimal nutritional and lifestyle habits – or that the one-a-day supplement offers a false sense of security. Additionally, the supplement industry is an unregulated one, and quality and dosage can easily vary across brands, as well as from bottle to bottle. That’s important to keep in mind when taking any supplement, but especially supplements as widely sold and produced as multivitamins.

Avoidance of Supplements

Here’s where things take another interesting turn. InsideTracker looked at biomarker differences in users who said they do not take any supplements at all, versus those who said they do. The prevailing view among the general public is that supplements are helpful for overall health as well as for a variety of conditions, needs and goals. The truth, as the data shows, is somewhere in between. Not all supplements are created equal in quality, as mentioned previously. And, not all conditions or goals can be safely or efficaciously addressed with supplements. With that in mind, a look at InsideTracker’s data reveals that people who do take supplements, compared to those who don’t, had on average higher and healthier levels of folate, testosterone, HDL, B12 and vitamin D, while having lower levels of triglycerides. Those are all good things, within the specified ranges. But here’s the interesting part: people who did not take supplements had lower levels of liver enzymes (ALT, AST), which is a good thing – but higher WBC count (and higher levels of 3 specific white blood cell types: neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes), which is not necessarily a positive thing, depending on the context.

Dietary Preference: No Diet Preference vs. Diet Preference

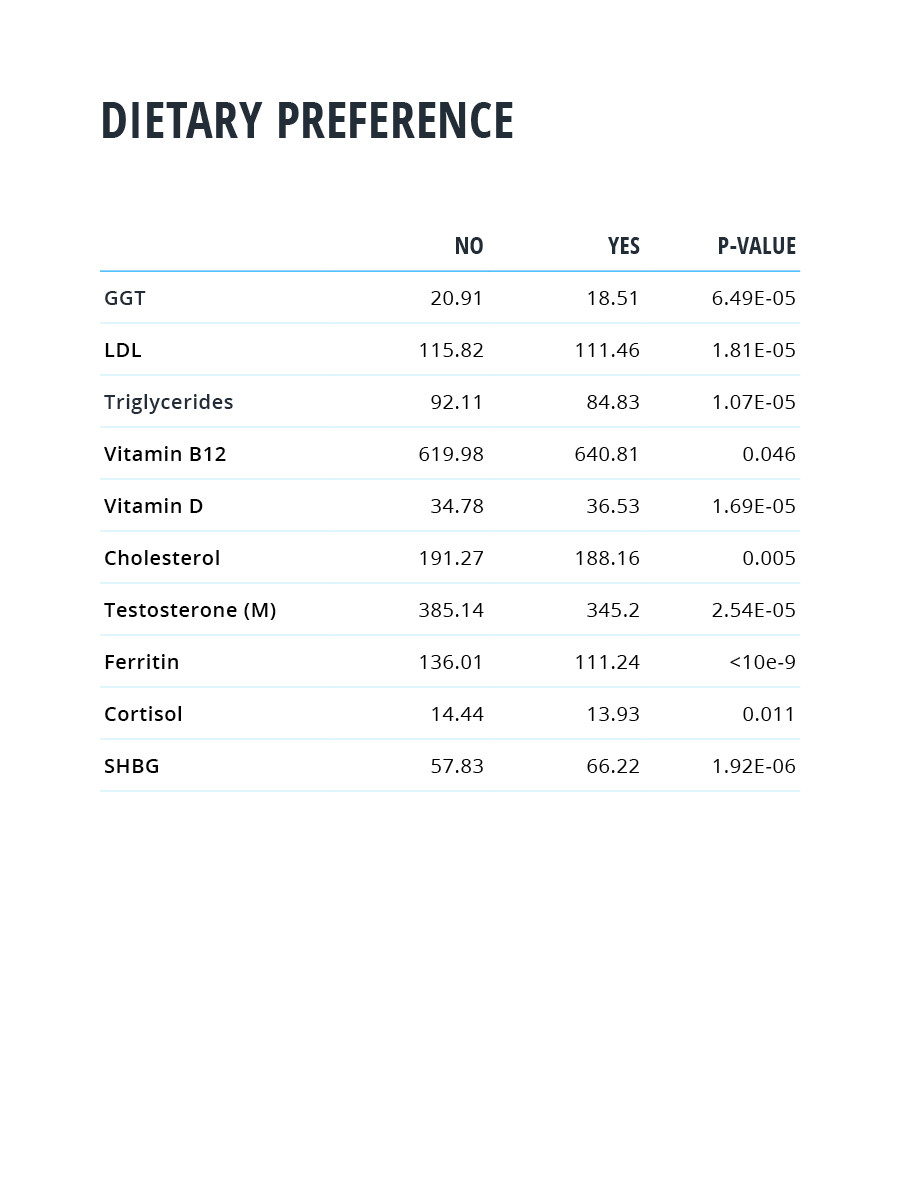

Everyday, it seems there’s another new diet trend: consumers are trained to believe that if an “expert” on TV or their favorite blog is touting a fad, that fad is worth considering. While that couldn’t be farther from the truth (caveat, emptor), it is worth noting that when it comes to the effect of diet choice on things like cholesterol, cortisol, vitamins D and B12, and inflammation, it may well be worth making a specific choice – with approval from your physician, of course (See Figure 1). A review of InsideTracker user data compared people who set no dietary preference at all, against those who indicated that they followed any specific diet (ranging from vegan to paleo and even narrower options). Statistically significant takeaways showed that compared to those who followed no diet, people who followed a specific diet on average had lower levels of total cholesterol, LDL (bad) cholesterol and triglycerides, lower cortisol, lower liver enzymes (GGT), and higher levels vitamins D and B12. However, those same diet-followers also had lower levels of ferritin (iron storage), lower levels of testosterone, and higher SHBG (which binds testosterone), than those who did not follow any restrictive diet.

Figure 1: The variation in some biomarkers based on whether one does, or does not, try to adhere to some specific kind of diet. The sample size is in the thousands.

Granted, there is more nuance within each diet type (the definitions of which often vary widely across the population) to be considered for further analysis. But it seems reasonable to hypothesize that perhaps those people who followed the guidelines of a generally healthy, specified diet, made more conscious choices about eating, selected less processed foods, or prepared their own meals more often, due to dietary restrictions. Simply being more aware of what one puts into one’s body on a daily basis can have far-reaching benefits on a myriad of wellness and performance outcomes. The act of restricting entire food groups can also have negative effects – as noted in the diet-follower group’s lower levels of ferritin, testosterone, and elevated SHBG.

This is just a quick and very simplified overview of what InsideTracker is doing. With dozens of DNA, biomarker, and behavioral measures, the company can explore an almost infinite array of associations. These are not always meaningful; some are just flukes. But over time, and with large numbers, the associations that truly matter can be separated out. As that list grows, so does the potential to deliver on the promises of personalized health promotion.

Marketing hype and false promises about personalizing medicine got here, inevitably, well ahead of evidence, and true understanding. Informed by the big picture inside each of us, that understanding is now catching up.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest