Comments

- No comments found

When it comes to the social media, everything you see is nothing more than an illusion.

The generation growing up now has never known social life without screens.

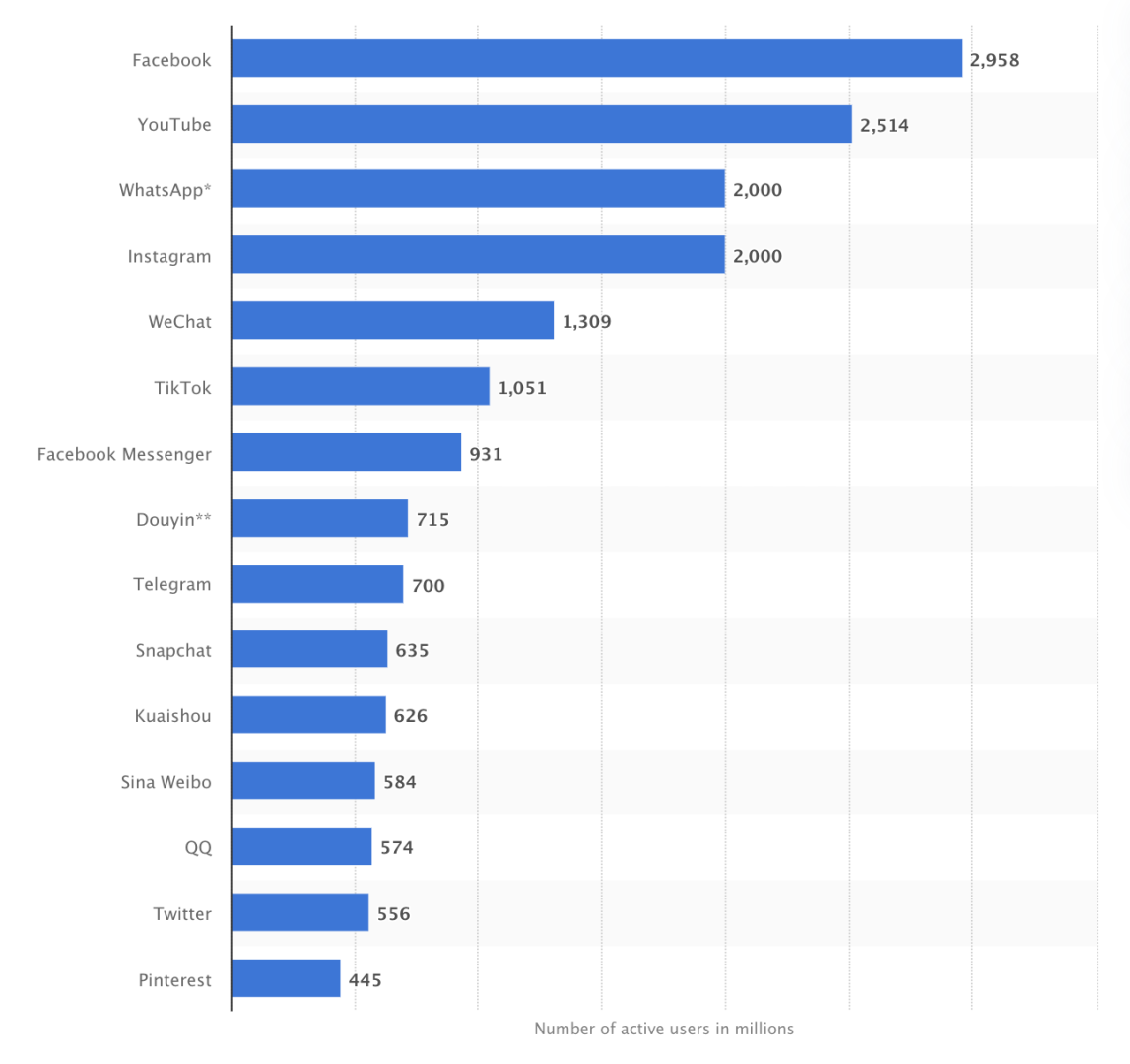

Most popular social networks worldwide as of January 2023, ranked by number of monthly active users | Source: Statista

At least one of the peculiar aspects of social networks is the manner in which a group of ideas, images, or messages can easily disperse like wildfire while, at the same time, others which appear equally appealing or captivating, hardly sink in.

The material, in itself, can not be the root of this discrepancy. Rather, there needs to be certain attributes of the network that transforms in order to enable some concepts to disseminate but not others of equal merit.

This is how I understood the term that the authors of a paper entitled "The majority illusion in social networks" label "the majority illusion". In any social network, Facebook being the mightiest of them all, most of the members will have a fairly similar number of friends. For the time being, take this premise as valid; I will go into it in greater detail in the succeeding paragraphs. There will be a few outliers who will have a much greater number of friends, usually several fold of the average. This is the source of what is known as the "friendship paradox". Most of the members hover around a fairly constant number of friends but the hugely connected stars skew the average upward, thereby making all the others come out as below average. If, somehow, you can take these super stars out of the calculation, then your ego will be magically restored.

If these relatively rare but well connected members possess some characteristic – say owing an iPhone or thinking that some YouTube cat movie is five star – the majority illusion kicks in. All other low-powered members, when they look around amongst their friends will see that the majority have that specific characteristic. If, on the other hand, the characteristic under evaluation is possessed only by the hoi polloi, then the rest of the group, looking around, will rarely see it in their friends. This is the majority illusion: the local impression that a specific attribute is common when the global truth is entirely different. Now you know why LinkedIn looks for and celebrates its Influencers and why your posts have very little chance of going viral and being the next Baby Shark Dance with its 9 billion plus views.

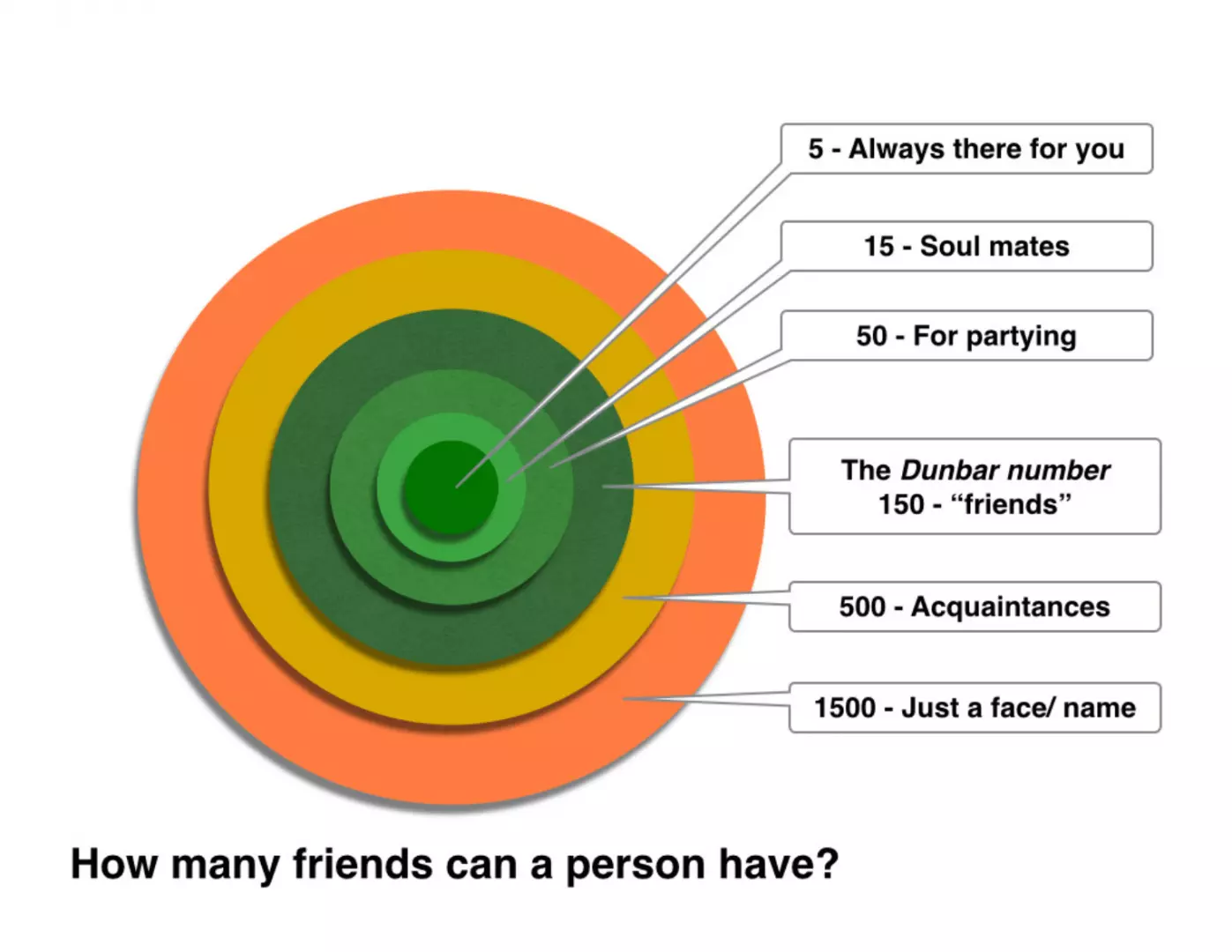

Now to the statement that the average number of friends is remarkably constant. Your first reaction is that it can't be. If nothing Facebook and Co. have vastly increased our capability to reach out and touch someone. Turns out that we are wrong. Several decades ago, a prescient anthropologist, Robin Dunbar, researched social behaviour in terms of brain volume of primates and stated that the number of people the average person could have in a social group was around 150: the Dunbar number. The figure has remained remarkably resilient over time. He also showed that this number breaks down in a fairly consistent rule of thirds. The first third — 50 — is the number of close friends most of us have — people you might invite for a large dinner or party. A third of that — 15 — the ones you can count on for sympathy and whom you can confide in for most things.

Finally, the last third — 5 — the ones you need when it gets really down and dirty. Expanding outwards: 500 is the limit for acquaintances and 1500, absolute tops for those whom you can put a name to a face. While the constituents of each fraction may vary — people falling in and out with each other — the number remains constant.

Studies show that the Dunbar number holds up in a wide range of situations that occur in society, over a remarkable span of history. Guess what? There is strong evidence that supports this distribution on Facebook. Hence, the strength of the premise for the majority illusion.

Arjun has spent four decades as a surgeon, educator and medical administrator. Fellow, Royal College of Surgeons of Canada and Member, Association of Surgeons of India, he has been associated with Sundaram Medical Foundation as the Medical Director since its inception and opening to the public in 1994. He did his residency training in General Surgery from the Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Illinois. After a 22-year stint as Trustee, Medical Director and Head, Department of Surgery at Sundaram Medical Foundation, he handed over the reins of the hospital but continues to provide advice and insights as Advisor and Trustee. Following his retirement from active practice, he has now embarked on a wider mission of forming a community of people, from all spheres of activity, who are interested in these three areas: thinking, teaching and talking.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest