Comments

- No comments found

Everyone knows that the economic future belongs to those who put technology and innovation to work.

One part of the formula for economic success for a high-income economy is active research and development, which then offers spillovers that are typically greater for the national economy than for the world economy as a whole. Dan Steinbock offers some additional perspective in ”American Innovation Under Structural Erosion and Global Pressures,”

a report written for the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

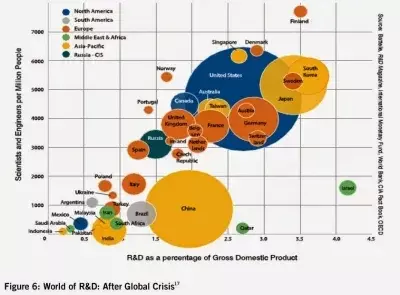

Here’s a picture of the global R&D effort. The horizontal axis shows R&D spending as a share of GDP for various economies. The vertical axis shows scientists and engineers per million people (thus adjusting for population size). The size of the circle for each country is relative to the total number of scientists and engineers: thus, China and India have fewer scientists and engineers per capita, but because of their large populations, the size of their circles is relatively large. The color of the circle shows the region of the world, as given by the key in the upper left of the figure.

Clearly, the U.S. position in global R&D remains fairly strong. But the US lags behind Germany and Japan, among others, in the share of its economy going to R&D. The size of the yellow circles–Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, China, Australia, and India–shows that the region with the largest absolute number of scientists and engineers is now the Asia-Pacific area. The U.S. has had a tradition of leading or being close to the lead in most areas of technology. As technological capacities expand around the rest of the world, the U.S. needs to strengthen its ties to the work being done elsewhere, increase the U.S. R&D effort, or both.

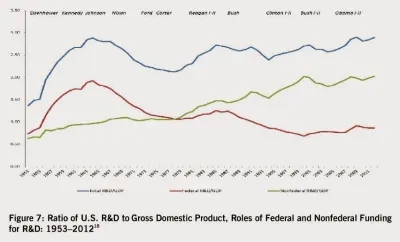

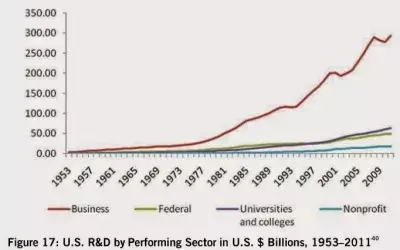

Steinbock lays out a number of trends in U.S. R&D. Here are a few that caught my eye. First, the ratio of R&D spending to GDP hasn’t moved much in the US since the 1960s, hovering around 2.5% of GDP. However, federal support for R&D has been falling by this measure over time, while the nonfederal share has been rising.

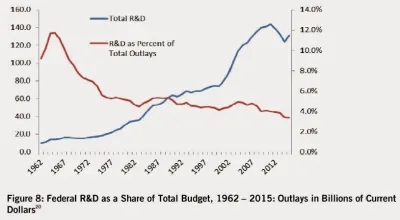

Here’s a figure showing federal R&D spending as a share of total federal spending (the red line). For four decades, while pretty much every politician talks up the virtues and importance of R&D spending, the share of the federal budget going in that direction has been sliding gradually lower–including in the last few years. Clearly, when it comes to political clout, researchers are slowly losing the battle.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest