Comments

- No comments found

Certain basic investment models are based on just two investment options: a safe asset like US Treasury bonds and a risky asset like a stock-market index fund.

The underlying idea is that you can choose the riskiness of your preferred portfolio by having a larger or smaller share of the safe asset. For example, a person who reaches retirement can decide to take less risk by reducing what share of their portfolio is invested in stocks.

But where corporate bonds fit in this scenario? There is something like $66 trillion outstanding in corporate debt around the world. Some of that debt is highly rated “investment grade” bonds, which in some ways resemble government debt–that is, safe but with lower interest rates. Another part is high-yield debt, sometimes called “junk bonds,” which seems closer to equities in having more risk and higher returns. (A professor of mine used to refer to “junk bonds” as “equity in drag.”) How do corporate bonds fit in the eco-system of finance?

Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh, Mike Staunton offer a long-run view in “Corporate bonds and the credit premium.” It appears in the publicly available part of the UBS Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2024, which is subtitled: “Leveraging deep history to navigate the future.” They begin with a wry comment: “Traditionally, bonds have been seen as boring, relative to stocks. In choosing the name James Bond, Ian Fleming said, `I wanted the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding name I could find.’”

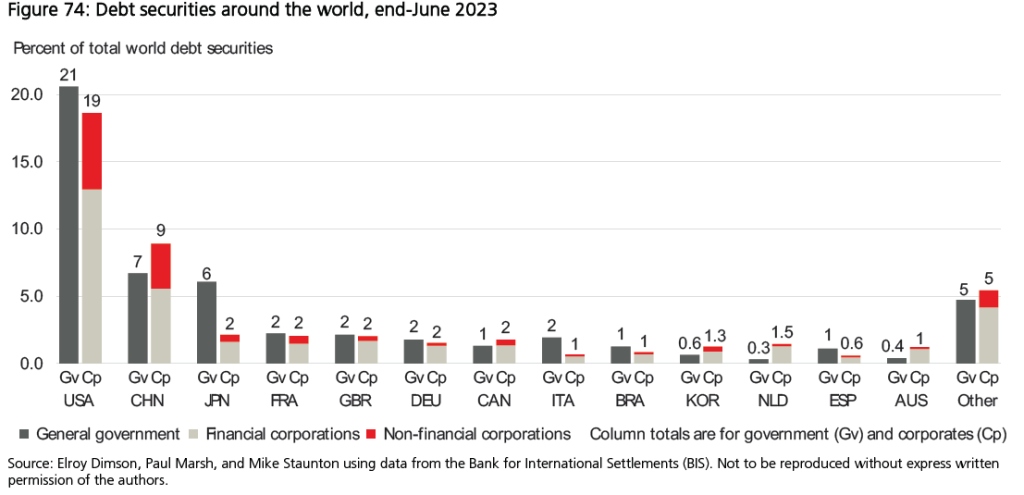

However, there’s big money involved in bonds: “[D]ebt securities worldwide have a value of some USD 136 trillion compared with around USD 100 trillion for global

equities. The debt total comprises some USD 70 trillion in government debt and USD 66 trillion of debt securities issued by corporations. Of this amount, corporate bonds account for around USD 45 trillion, the remainder being other corporate issues.”

Here’s a figure showing the distribution of debt securities around the world. The US dominates corporate bond markets in part because of the sheer size of its economy, but also because of the depth of its financial markets. Also, the role of corporate bonds is different in the US economy than in many other countries. In “bank-centered” economies, corporations often have very close ties (including cross-ownership) to one or several banks, and thus can raise money through those connections. In contrast, US financial markets are more likely to push companies that want to raise money to go “to the market,” and raise funds from outside investors.

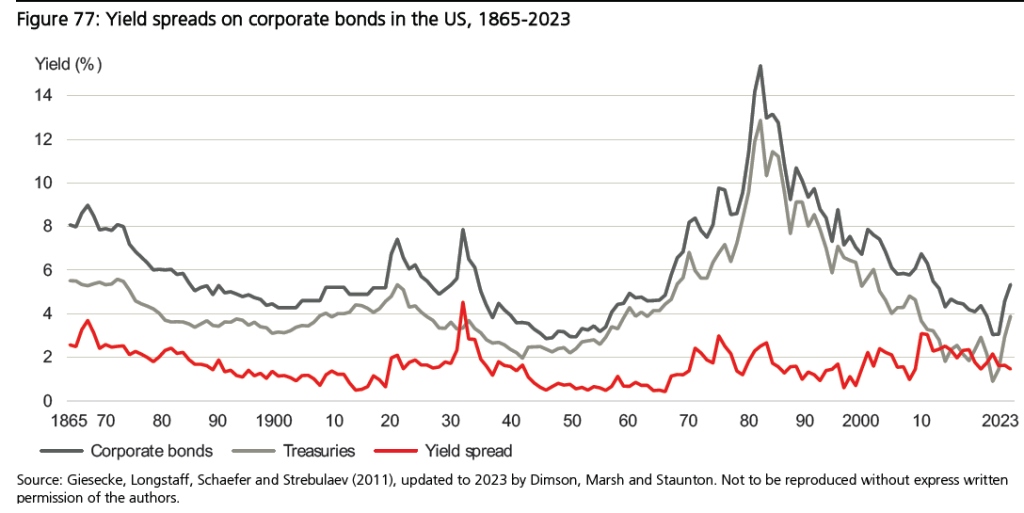

What do returns on corporate bond investments look like over time? The figure shows returns on US Treasury bonds as the light-gray line, and returns US corporate bonds as the dark-gray line. The red line shows the gap between the two: that is, what is the extra return or “premium” that an investor gets for taking on the extra risk of corporate bonds: “”Over the 158 years spanned by Figure 77, the credit spread has averaged 1.58% with a standard deviation of 0.73%. The lowest spread was 0.42% in 1965, while the highest was 4.53% in 1931.”

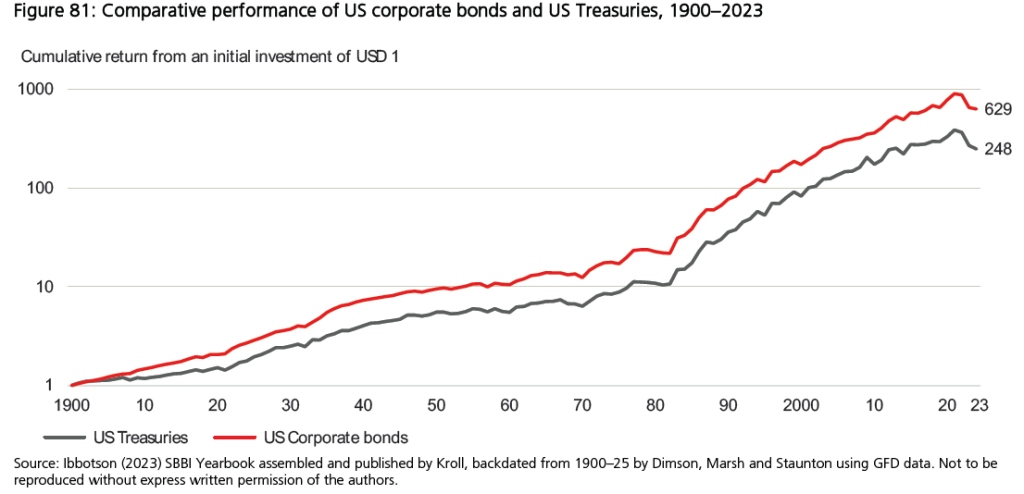

Corporate bonds have higher return, because of their higher risk. As a result, they will outperform safe US Treasuries over the long run

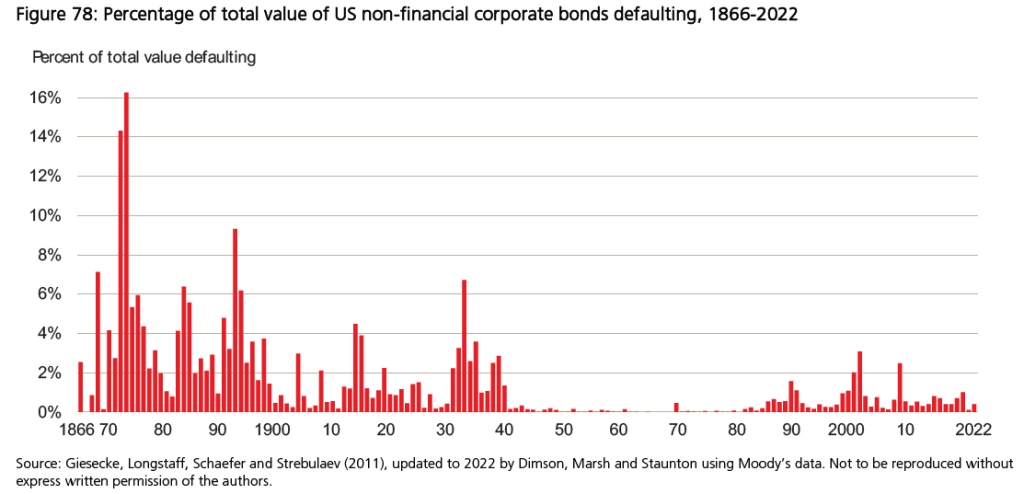

One obvious risk for corporate bonds, as compared to US Treasury bonds, is that corporations are more likely to default than the US government. Of course, a default doesn’t mean that investors lose 100% of the value, but they can often lose half or even more. However, the share of the total value of US nonfinancial corporate bonds ending up in default has been declining over time.

To return to the question at the top, what role should corporate bonds be playing for investors? In a situation with a safe asset like Treasury bonds and a risky asset like stock market index funds, are corporate bonds more-0r-less superfluous? The UBS authors emphasize that they are not offering advice about future investing. Like the advertisements for investing are required to say: “Past performance is no guarantee of future results.”

However, they do cite several studies that looked back in time and calculated what would have been an optimal portfolio if you could choose between government debt, corporate debt, and stocks. Looking back at the past, at least, the optimal long-run portfolio would have included corporate bonds. Indeed, one study found that over the long run, the optimal portfolio from 1936-2014 would have included a larger share of corporate bonds than either government debt or stocks.

What about strategies to make money in bonds short-term? Again, the authors are careful to point out that it’s easy to point to the investments that would have worked in the past. But especially after such strategies have been publicized, there’s no guarantee that the strategy will continue to work in the future. But for completeness, the authors also mention a few limited and intriguing exceptions. One involves “fallen angels,” which is corporate debt that was once highly-rated as investment-grade safe, but now its credit rating has declined to the point that it has become a high-yield “junk bond.” Here’s the dynamic that can unfold:

Most mandates for IG [investment-grade]corporate bond managers require them to sell bonds within a relatively short time-span if they get downgraded from IG to HY [high yield] status (typically bonds being downgraded to BB). These bonds are commonly referred to as “fallen angels”. The need for a substantial number of

investors to divest within a limited window appears to have created price pressures that temporarily reduce prices below their fair values. Historically, it has been profitable to buy these fallen angels. Ben Dor et. al. (2021) analyzed the fallen angels effect and report an extensive pattern of strong price reversals. Their results suggest that investors start selling in anticipation of the downgrade before it happens and continue to sell until around three months after. The price falls are then reversed and fallen angels outperform by a total of 6.6% in the two-years post downgrade. The greater the initial under-performance, the higher the subsequent returns. They conclude that this is due to price pressure rather than an overreaction to the information implied by the downgrade.

This “fallen angel” price dynamic has been noted for some years now even after being published in the literature, but at last check, it does not yet seem to have disappeared. Of course, it could easily disappear in the future.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest