Comments

- No comments found

Psychiatry, as a field, requires functional repairs.

Two recent books “The Mind and the Moon,” by Daniel Bergner and “Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness” by Andrew Scull, as well as “Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness” written a few years ago by Anne Harrington went deep into the history of the field exploring the strangeness of supposed causes, cures and continued deviations.

Serious mental illnesses are said to have biological basis, but biochemical targets have not been as broadly helpful as possible.

There is a complex purview around molecular targets, but first, what really is mental illness? Or simply, what is mental health?

What is mental or say what is mind?

What are the components of both?

These questions may seem too basic, but maybe not seeking out those compounded problems that persist.

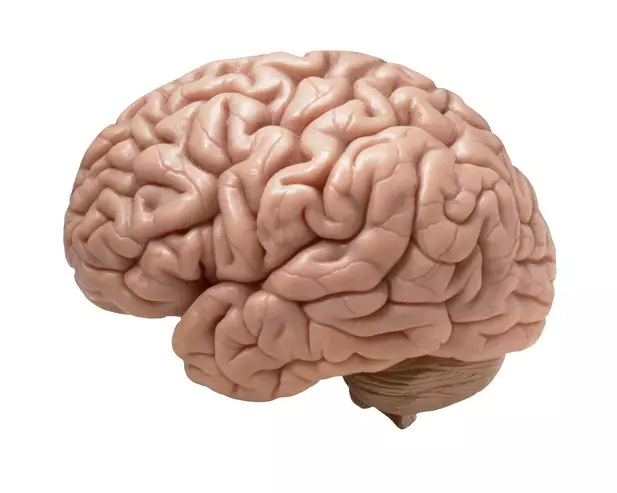

The brain is the host of the mind. The brain has nerve cells—with electrical and chemical signals. The brain has hemispheres. Respective hemispheres have lobes. The brain has white matter, grey matter and so on.

However, where is the mind, in the brain?

There are advanced microscopes that can, in high resolutions, see deep connections in the brain. Functional MRI can explore brain activity while in use. EEG can track brain waves. Brain-computer interfaces can assist motor and speech functions—from cortical areas. Deep brain electrodes can monitor and stimulate electrical impulses.

But where exactly is the mind, in the brain?

This is different from the explorations of consciousness—which is what it means to be and to know, but ignores thought and memory as possible answers, while seeking far afield stuff in the universe, quantum or some abstractions.

What is the mind, as a possession, to an individual? What is the way the mind helps to know about the world?

If someone sees a car, knows the car and understands much about the car, how did that become possible, without first putting the car in the brain?

There are remarks on predictive coding or predictive processing—in neuroscience—of the brain making guesses of the world and correcting prediction errors, but how the brain exactly does this remains unanswered. If the brain were actually making guesses, won’t random slips have led to severe social problems?

A few years ago, the current director of the National Institute of Mental Health, NIMH, Dr. Joshua A. Gordon, was an author in a study, ‘Brain “relay” also key to holding thoughts in the mind’ which explored extra roles for the thalamus.

Another author, Dr. Michael Halassa of MIT, explained thalamic role in complex thought.

A study “The role of the thalamus in sleep, pineal melatonin production, and circadian rhythm sleep disorders” discussed opening of the sleep gate in the thalamus which can be explained as a port that opens for sleep and closes for wakefulness.

It is established—in neuroscience—that there are sensory processing or sensory relay centers in the brain: the thalamus for all senses, except smell, relayed at the olfactory bulb.

There is multisensory integration, exploring what happens to senses in the thalamus before relay, or what happens at a relay center before procession.

The landing decks are the first stop of external stimuli to the brain before transport to the cortex for interpretation.

Why is sensory integration necessary? Or, integration is into what: same as the input quantity or something different?

These are important questions towards tracking the transports of the mind.

The mind [or mental] is two things: thought and memory. Memory is at locations, but thought transports across. Neuroimaging does not see or show thoughts.

Mental health could be healthy transport of thought across memory areas. Mental illness could be ill-transport of thought across the memory, or problems in memory areas.

Cellular and molecular specifics are contributors but their constructs [thought and memory] could be the bigger problem.

Where does thought come from? Where does thought go? After thought emerges, is there somewhere else it finds further transport?

It can be proposed that what sensory inputs become at relay centers are thoughts or a form of thought. It is what gets relayed, for interpretation, which includes knowing, feeling and reaction.

It is also thought or a form of thought that the memory stores.

The car was not put in the head to know, but was a sensory input that was integrated into a form of thought. It is the thought version of the car, house, and so forth that is used to relate with the world.

Knowing is the memory. The memory has groups and stores. Stores can be proposed to be capsules of thoughts in the smallest of units that transport across groups—bearing similarities. It is what groups a store goes that determines what to remember, what to feel-like and so on, before the thought proceeds to the destination for feelings and then reaction—which could be parallel or perpendicular.

There are different studies on beneficial activities for mental health like viewing art, walking, talking, and so on.

How so?

Maybe they became thought versions and went to locations in the memory to compete—for priority—with whatever is responsible for the bad mood.

These, though theoretical, could be a way to converge mental into thoughts [and memory] so that their pathways are displayed for those living with conditions and their loved ones to understand where thought is in an episode, or what the memory knows, or allows.

In a review of Daniel Bergner’s book, there was a quote by Professor Steven Hyman of Harvard that “How people could think that mediocre — important, but mediocre — drugs like the SSRIs could give us any comprehension is beyond me. The logic is like saying, ``I have pain so I must have an aspirin deficiency.”

It is true that serious mental illnesses are hard, but thought and memory are parts of their mechanisms.

Structuring both is not the cure, but knowing where the delivery is before arrival helps.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest