Suppose that jobs went away. Not all jobs, mind you, but many, perhaps upwards of 90%. Some of those are in hard-manual labor territory, like coal mining. Some are in the services industry such as driving a taxi. Some are in high tech, like programming. Not a few will be in areas such as sales and management, politics or journalism. What happens next?

This is one of the fundamental questions we collectively need to answer as we move into the fourth industrial era. I first posed these questions about twenty years ago, and have found that most of the what I wrote came to pass. The answers haven't become much more obvious, even as the effects that I was observing at the time (and even as far back as the 1980s) have become sufficiently pressing to topple governments, including arguably, in the United States.

Here's the cliff-notes: We're now IN the fourth industrial era, have been for about forty years. We're also IN the third industrial era, the waning of same. There's no clear hard and fast definition, but a good starting point for reference would be the creation of ENIAC in the years after World War II, or perhaps the first transistors in the 1960.

The third industrial era started in the 1890s, when petroleum edged out coal-fired steam as the preferred mechanism for powering horseless carriages - thus creating both gas and the cars that ran on them. It was the era of Bell and Marconi and Farnsworth The second industrial era started with the advent of the steam engine as a commercially viable tool, though it would take the replacement of wood (or charcoal) with mined coal for these to become powerful enough to drive ships, riverboats and trains. Communication there was limited to the telegraph, along with an explosion in printing technology. Prior to that most industry was managed by wind, water and human or animal muscle.

What's notable about this list is, first, how much it is driven by certain types of energy. The fourth industrial age is marked most notably by photovoltaics cells, capable of translating light into electrical energy, but also by the prevalance of stored rather than transmitted energy. It may, possibly, be marked by fusion, though the jury's still out on that one. It most certainly is marked by the introduction of increasing levels of distributed intelligence in everything, that is, giving things the ability to make decisions.

Yet in addition to that is the awareness that the era of muscle power is still present, albeit in very limited fashion, coal still drives many a steam turbine, and gasoline powered cars still dominate the roadway. The fourth industrial age, in that respect, is an overlay, rather than a replacement, of what came before. The future is here, it is just not yet evenly distributed, as science fiction author William Gibson famously once said.

What defines an industrial era? In many respects, it is the nature of work itself. Industrious means productively busy, doing something that achieves a definitive goal. If you dig a hole, then fill it up again, you are not being industrious, you are just being foolish. On the other hand, if you dig a hole, drop a coffin in, then fill it up, you are being industrious. The first has no value, the second does, despite the fact that the actions are (almost) identical.

In the first industrial age, most physical work had value. You dug graves, planted barleycorn, forged swords and plowshares, sewed clothing, fought in battle. There were simple machines that could be used to transfer energy, but they very seldom actually multiplied it any meaningful way. In comparison to the average person today, most people in this era were incredibly strong - they had to be, because this was the only way that most meaningful activity took place.

Wealth was based upon land stewardship, and feudalism was ultimately a system whereby a ruler subdivided territory into smaller units. The ruler was responsible for the overall defense of that territory, and for that responsibility was awarded both the ability to elect vassals and to establish taxes (make a profit) on the goods, food and services being produced. The ruler also reserved the right of seigniorage - the right to mint coinage, with their sign or sigil upon each face. Within a kingdom or province, this let them control the money supply (outside the kingdom, of course, it was usually the weight of the various metals in the coin that determined the value of the coin, so there was always a trade-off for any sovereign about how much they debased their coinage).

Trickle down economics is hardly new - it was in fact the dominant form of economies in feudal times. Peasants and freemen seldom saw coins and usually traded via barter - five chickens for a pig, a space to sleep and meals in the morning for help taking in the crops, and very occasionally the baron buying the dresses your wife and daughters had sewn with coinage that would then be traded as just another barter item. Coinage became more important in cities, where you didn't have the space or means of storage for bartered goods, and it was in those cities where the notion of a labor market began to emerge (especially towards the end of the feudal era).

This all changed with the advent of the second industrial age. Physical labor was still prized, but steam powered engines began to replace first heavy physical labor (such as mills), then highly repetitive tasks (such as sewing or weaving) then tasks that had not been done because they required continuous human intervention (such as pumping out water from mines and later tunnels, which also made getting access to coal much more feasible). Labor went from being seasonal and sporadic to being regular and needing a reliable concentration of workers continuously. This became the rise of the wage economy, because those workers needed to be housed, clothed, fed and kept at least moderately motivated to stay.

The aristocracy that relied upon agriculture watched their revenues plummet, while those who had the means invested in the new factories (places where things were made, literally). Meanwhile, the factory owners and managers became the new rich. One effect of this process was to create a new "working class" that had the same coinage without those coins coming from parsimonious land-owners. For those in early management, this became the ticket to becoming part of a new burgeoning middle class, and these people in turn created new shops to sell these goods to a hungry market. Railways and steamships increased this network dramatically, as did the rise of telegraphs that made it possible to communicate both personal and financial news in minutes rather than days.

The third industrial age came with the harnessing of oil, rather than coal. Petroleum was considered a useless byproduct of harnessing coal, and while it had some value as a lubricant, quite a lot was simply burned off. That all changed as materials engineering made it possible to better fraction petroleum by weight of its various chains of hydrocarbons, which in turn led to the internal combustion engine. Coal powered steam engines were simply too big and required too many people to use for powering personal carriages, but the internal combustion engine was just the right size.

One of the fascinating things about periods of innovation is how so many things all seem to come together at just the right time. More cars required more (and better) highways, which required larger government intervention cutting across boundaries. If coal-filed steam created the modern urban core, oil created the suburbs. World War I was fought primarily as a race to secure the oil-rich regions of the Middle East, which had, until that time, simply been part of the dying Ottoman Empire. With oil, these countries gained huge significance, and a significant portion of World War II ultimately came down to Germany attempting to control (and for a while succeeding) the areas now known as Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Syria and Israel (at the time Palestine). The Japanese expansion was also focused on securing oil assets, primarily in Malaysia. In the end, it was America's position as a major oil producer that ultimately let it effectively take Great Britain's (Coal driven) empire and make it its own.

In the 1930s, most of America was largely agricultural, and the vast majority of all Americans worked either on a farm or in food processing. By the 1950s, there was a massive migration into the cities (and the suburban bedroom communities) as servicemen, coming back from the war, went to work either directly for the petroleum industry or in finance, the military industrial complex, or the new consumer retail sector. The corporations of this era were huge, employing hundreds of thousands of people each and tens of thousands of managers just to coordinate all of these actions. Every transaction generated paperwork, and this meant that someone had to process that paperwork. Corporations looked like the military, partially because that was the organizational model that most people knew and because the military of the day was huge - roughly one person in ten had been in the service in 1944.

The computer and the network changed all that. By the 1960s, computers had replaced humans in the production and processing of bills. By the 1970s, it was beginning to impact design and the automation of factories had gone from being primarily mechanical to having very basic levels of intelligence. By the 1980s, as networks started to build out within corporations and personal computers began to emerge, desktop publishing did away with the secretarial pool, managers were being "consolidated" and those that were left were the ones that had mastered spreadsheets.

By the 1990s, all of these networks were increasingly connected by the Internet, and while a raft of new jobs were created, this largely masked the old jobs going away in publishing, retail, process management, and manufacturing. Supposedly safe jobs like being a lawyer or doctor were beginning to look less safe, and wages remained static. Meanwhile, upper management and investors were reaping a bonanza as companies required fewer and fewer people to run them. That automation dividend did not go to the people who lost their jobs, but rather to the investors who had put the automation into the companies in the first place, while creating the rise of the technical professional class.

The 2000 Tech Recession occurred because the hype about technology exceeded the capabilities of the technology, and for about three years, the field went into seeming quiescence. It did force a lot of people out of IT that were at best only marginally involved with the technical aspect of it, and showed that, unlike in the heyday, while getting rich in IT was still possible, it was hard work. For every Larry Page or Mark Zuckenberg who became astronomically wealthy, there were a thousand programmers who ended up going from job to job, each lasting perhaps eighteen months, as the first people truly in the "gig" economy, making enough to modestly comfortable, but far from wealthy. It was also a period where operating systems became commoditized, expecially as Linux went from being a curiosity in the late 1990s to become the most universal operating system in use (even Windows 10 now has a workable Linux kernel built in, and Android and Chrome systems are all built on it).

These systems in turn supported the emergence of a cloud infrastructure where software (and perhaps more importantly databases) could be run as a service. Couple that with remote point devices (smartphones, which are essentially hand-held computers that include a fairly insignificant calling capability), and you could run a company the size of IBM (100,000 strong at its peak) with a staff of perhaps a hundred people. Note this doesn't mean you had a thousand times the number of companies - there are perhaps ten times as many as there were fifty years ago. Rather it means that there are three orders of magnitude fewer jobs today than there were in 1965.

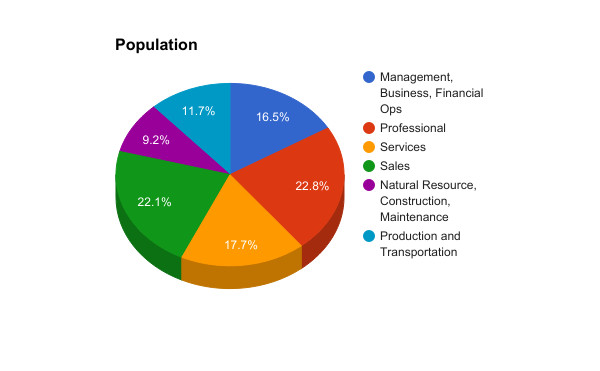

This is huge, but if you look at employment statistics, it is also seemingly erroneous. The US, for instance, is very close to full employment in terms of the number of jobs. However, it's worth looking at where those jobs are. As of 2015, the Bureau of Labor Statistics broke down jobs as follows:

Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey

The professional sector makes up about 22.8% and includes doctors, legal professionals, media creators (including performers), IT professionals, researchers and educators. Sales is only slightly smaller (22.1%), and includes both retail and wholesale (B2B) sales, while management and business support make up 16.5%. Production includes both manufacturing (about 7.5%) and transportation (4.2%).

This is a profound change from even 50 years ago, where professionals made up perhaps 7% of the overall economy, services about 10%, and sales perhaps as much as 30%. Management has also been declining from the mid 20s. Production and transportation has also dropped from 25-30%, and manufacturing in particular continues to decline.

Most of this can be attributed to automation. While there has been a perception that most of the jobs that have "gone away" have been from manufacturing, that's actually a bit misleading - the first stage of the 4th Industrial Era has actually hit management jobs particularly hard, because they were the most readily handled by new communication paradigms. Marketing and sales, which were strong in the twentieth century, have also been hit hard as more and more of the brick and mortar infrastructure becomes virtualized. Malls and "big box" stores are increasingly being shuttered as companies such as Amazon wreak havoc in the physical retail world, and especially in urban areas, the corner grocery store or bodega is being replaced by delivered groceries from online grocers or even ready to eat meals replacing "going out".

This is a boom time for delivery services and transportation services, yet even here there's a massive storm brewing with the rise of autonomous cars (and more importantly) autonomous trucks. There is a distinct shortfall in the current number of available truck drivers in particular, but autonomous, self-driving trucks are in a position to destroy the transportation labor market - and to reshape how we build businesses.

Professionals have benefited from the fourth Industrial Age, but the phenomenal growth for IT in particular has been slowing, and has been shifting away from production of code to data analytics. Education, which emerged in response to a scarcity of available information, has been forced to rethink itself in light of too much information. Entertainment (media production) has been growing, but that is increasingly concentrated in the games sector, which has now eclipsed movies and television in terms of total revenues.

Given the desire (and given the increased evidence that we are undergoing significant climatic change, the need) to reduce the overall pollution that is produced in a petroleum economy, the shift to solar, wind and similar renewables is well underway, and is replacing petroleum era jobs that can be done with a high school education with solar era jobs that require a college education.

These all point to professions "in transition" or even more, "in danger". Most of those dangers come ultimately to areas where artificial intelligence, drone/bots and additive rather than subtractive manufacturing, come to play. Indeed, these three areas, along with alternative technologies, should be seen as hallmarks of the Fourth Industrial Age.

Artificial intelligence (AI) does not mean that computers are "human aware". We are likely still decades away from that particular goal, if ever, but even without human awareness, AIs are forcing us to rethink both economy and society.

An AI is a computer system that is capable of modeling the world, then based upon that model, perform specific actions. This differs from primary programming in that most programs are modeled by humans then react to that world. A facial recognition system is an AI that identifies key biometric points (the position of eyes, location of the nose and chin, and other subtle variations), then performs spacial skews on this in order to generate a given identifier for that purpose if the person is unknown. If the identifier already exists, then a stored set of actions are initiated, if the identifier doesn't, then the data is stored and compared against other data systems. Almost all AIs work on this kind of feedback loop - Resolve, Analyze, Classify, Store, Act. A voice recognition system works this same way, as does an autonomous traffic control system.

The key here is that as the AI classifies and stores, it also changes its model.

In other words, AIs learn.

It is this facet which makes AIs so powerful. AIs can learn to recognize patterns, and having learned them, can take more complex actions without needing to be explicitly programmed. A very simple example would be something like the HVAC controls in a modern car. If I get into the driver's seat, and the temperature is cold, the HVAC system may check first to see if the temperature is below freezing. If it is, then (because this action was established the last time the temperature was that low) it would know first to blow warm air to defrost the windows for about ten minutes before automatically switching over to the blowers in the driver's side of the car, because this was the behavior it observed.

If my wife was in the car, then it would know to lower the louvres (she's smaller than I am) but to turn the temperature on that side of the car up about four degrees warmer (she loses heat faster than I do). If she's not in the car, then it might turn of the blowers on that side once a core temperature was reached. If I change the set-point, then the AI should be smart enough to remember that new set-point, without me explicitly telling it to.

Now, apply this to a business. An AI looks at a number of different market variables, economic indicators, sales figures, new products based upon existing products, needs for hiring or laying of workers and so forth. The AI's purpose is to maximize certain things (shareholder profit) while at the same time staying within specific regulator parameters. At certain points it may look at certain acquisitions (buying up a company, or hiring a new programmer or designer) and will see how they behave). Now most contemporary computer systems are capable of running many years of this model with various input in the course of a few hours, even given a very complex model.

Similarly such systems can buy or sell stocks, or options, and generally optimize for output, often at nano-second speeds. They can (and regularly do) do this now. If you go to most commodity or stock exchanges, you may notice that, where there used to be hundreds of brokers on the floor trading, now there's nothing. The trading floors have gone away, and the traders (the salespeople) have been replaced wholesale by machine-learning experts building AIs. It isn't a one for one trade - two or three such experts may replace a hundred traders, and after they've set up the system, may only be called in to tweak the system to improve performance.

The bulk of all sales and marketing jobs are going away, or are being turned into social media jobs (at a rate of about 5:1 at this point). There is simply not enough value for intermediaries to make a living given the low differential involved. Fewer sales people mean fewer general managers, while technical managers have largely peaked out and will follow within about a decade.

A drone is an autonomous robot capable of mobility, connected to an AI. The drone contains sensors - such as cameras, microphones, GPS indicators, gyroscopes and in some cases even infrared or ultraviolet sensors. A small hoverbot is perhaps the most recognizable drone, but an autonomous car is a drone, an autonomous truck is a drone, even an autonomous building is a drone. Their intelligences are very focused (and in almost all cases there are networks of interacting AIs within each of these), but the effect basically is that the drone is simply the AIs means of interacting with the outside world.

Drones are augmenting window washers, helicopter pilots, building inspectors, and are increasingly performing security work. They will likely make up the majority of all taxi vehicles by 2027) and will likely replace the bulk of all truck drivers by 2030. In the interim, truck drivers will increasingly be passengers, such that a truck may very well drive 24 hours a day while the driver becomes the backup and security agent. Mining is going this same route, with autonomous augers, borers, and transport. Saving mining jobs at this point is kind of pointless - they are disappearing due to automation faster than they are (much faster in fact) than they are due to cheaper coal, steel or other extractive materials.

Additive (or 3D) printing is also contributing to the decline in jobs. Yes, there are likely to be great opportunities if you happen to be a 3D specialist, but most manufacturing will become hybrid systems where you have a mix of mass production with mass customization, allowing you to create a wide number of variations off the same basic template. Again, the limiting factor is the skills of a good 3D designer, but the skills necessary to do video game world development is the same as to do 3D printing. This should kill what little manufacturing labor now exists, in favor of a much smaller cadre of technical professionals.

Databases are the other arena that will radically trim even the professional classes. Some teachers have gone into interactive educational systems, but it is likely that teachers will increasingly become online guides, especially at upper grades. This process is already well underway at the university level. Lawyers are struggling, especially those who are primarily researchers - with too many lawyers being produced given the easy and inexpensive availability of searchable legal codices.

This is not to say that all of these jobs will disappear - there is a lower threshold where you do need people, but it's a lot lower than most people would like to believe. This means fewer hours for work available for vast swathes, people moving involuntarily into the just-in-time gig economy and the not so slow collapse of third industrial age capitalism.

All of this seems like the end of the world, and let's be honest, it is. It is the end of the petroleum age and a way of life that's been in existence for about 125 years. It's the end of life for building massive cities and spending hours a day getting to them so that you could sit in a cubicle and perform repetitive tasks for nine hours a day (who here doesn't usually work through "lunch"). It's the end of life for technology that pollutes the land, the water, the air, that keeps people chained to a desk, and that fails to provide the basics of health care or a decent education for all its citizens. It's the end of wars of conquest for oil, and for many countries, it's the end of a dependency upon that oil that has created some of the most repressive regimes on the planet.

For many people these things will not be missed. Yet it also means the end of a reliable paycheck, and the means by which you pay for goods and services. Indeed, when you get right down to it, what is terrifying about the fourth age is precisely this lack of paycheck. How do you pay for goods and services? How do you "make money"? How do you eat, raise a family, do any of those things that are the positive side of the third industrial age?

To answer that, it's worth going back to the notion of an exchange of value. In our current society, the value of a transaction is determined primarily by an exchange at a personal level. Economists speak of both the buyer and the seller having complete information - that is to say, in setting the price of a good or service, both the buyer and seller will seek an optimal price and have equivalent power to set that price. In reality, however, most transactions are asymmetrical - one side has the right to accept or not accept a job, but the rate being paid is fixed, and tends to be more asymmetric the greater the comparative need is. If you are already wealthy, you have far more bargaining power, if you are not, then you typically have to take whatever job is available.

What the fourth industrial age does is turn that model on its head. One person paying a writer to produce a work (the patronage model) only works when the commissioner is wealthy. Ten thousand people, each spending ten dollars to support an artist (the patreon or kickstarter model), means that artist is clearing $100,000 a year. Each of those micro-patrons, however, is less likely to spend that money when it is going to an intermediary. 4IA economics rewards creators, and punishes go-betweens (whereas 3IA economics did the opposite). In essence, it turns a person (or more precisely a small team of people) into an investment vehicle, where the goal of that vehicle is the commissioning of product.

The same model works with most small, focused professional organizations. The investors are getting tangible results for their money, not necessarily financial returns. You see this in open source software, in government transparency initiatives, in physical remediation of polluted environments, in providing for basic housing, in the funding of research. Much of this used to be done by the government, but that government has reached a point where most of the tax money collected goes either to the payment of debt, a highly bloated defense budget, or increasingly to pointless projects such as a wall across the Mexican border.

At the same time, demand for physical goods - the very things that the third industrial age develops so well - continues to drop, with a shift towards an increase in demand for experiences. Study after study shows that Millennials are buying fewer things, are electing to delay child rearing or opting out entirely, and are far more focused on doing things than buying things- and are increasingly competing with their former producers to do so. This is de-legitimizing the third age institutions, not just governmental ones but corporate, educational, religious and social ones as well. What's replacing them are microcompanies, micro-schools, a shift toward religion as spirituality rather than the megachurches of the 1970s and 80s. It's shifting of power to the local and away from a centralized control system, which in turn has had a profound impact upon politics.

The election of 2016 will likely be seen in retrospect as one of the most significant of the last hundred years. It exposed the growing divide in both American political parties between a fourth industrial age focused population and the more "conservative", still largely third industrial age one. Less than 50% of the eligible population voted, and most were swayed primarily by a barrage of disinformation within the last week of the contest. Most of these people were people who were the most resistant to the changes brought about by the shift away from the Petroleum economy - social conservatives, those who had been "unmoored" when their skills became redundant, those with comparatively minimal education or the ability to adapt quickly enough in the face of that change.

There were more people on Facebook in this country than voted on either side of the election. Many see both parties as being too centralized, with participation largely affected by political committees that are unresponsive to their constituents. This is especially true of Millennials. There are strong indications that the GOP, as the de facto representatives of third industrial age business, are in the process of massive overreach, and will most likely end up unifying those under the age of fifty in opposition. But traditional Democrats are discovering that their constituents are now running dramatically ahead of them, promising primary challenges to those on the Democratic side who aren't progressive enough - not just socially but technologically and fiscally.

This is an indication that the duality of viewpoints that has been the hallmark of politics in the 20th century has become a plurality today, and it is reshaping how politics happens. Political parties are a 19th century, steam age invention. They arose because of limited communications speeds, where only the wealthiest or most desperate had the means to use the new-fangled telegraph, and the newspaper was becoming the dominant form of broadcast communication. Building consensus across a wide array of interest groups was difficult and time consuming, and as such keeping the choices down to two, where the candidates were fronted by different caucus organizations made a great deal of sense.

In the age of radio/television (which, along with the car and gasoline, formed the third leg of the technology triad of the day) the country moved from regional consensus (there were no real national newspapers at that point) to national consensus. One viewpoint represented the side of labor, the other the side of business. In the 1970s, that equation changed, as the conservative Southern Democrats switched to become Conservative Republicans, while many urban, affluent (and increasingly female) coastal Republicans jumped to the Democratic side. This led, forty years later to the Clinton Archipelago and the Trump Heartlands (in a fascinating set of maps as rendered by the New York Times.

What is so fascinating with this is that each of these represents roughly half of the American voting population. The Heartlands are dominated by third industrial age industries and are mostly rural or lightly populated. The Archipelago are dominated by fourth industrial age industries and are mostly urban or are centered around research facilities or universities. The archipelago is racing towards a fourth industrial future, while the heartlands are holding onto the third industrial age with tenacity - and it is this, as much as any factor, that is tearing the country apart.

Automation is fundamentally deflationary. You are producing more goods in less time, which means that eventually you end up creating excess goods. The third industrial age's solution to this was marketing, specifically creating artificial demand. The mantra of this era was consequently one of "growth", growing a market for a product. This process produced a lot of waste product - extraction waste, goods that were never purchased, goods that wore out, production waste.

That changes once things begin to become smart. Intelligence adds to the value of things in terms of performance, but it also adds in terms of being able to gauge (and increasingly to repair) damaged systems. Hardware intelligence - intelligence on chips - gets replaced with software intelligence once processor speeds exceed a certain minimum threshold. Today, most electronics have become consolidated into a form factor that is becoming near universal - the smart phone.

"Smart phone" is a misnomer. The device includes a speaker and microphone for converting analog devices to digital and vice versa, but this is a very ancillary part of the overall device. It is, in essence, a handheld computer connected to a wireless network. Somewhere along the line, we tumbled onto a few form factors that seem to work remarkably well - a screen that also contains the intelligence, a keyboard (probably wireless and detachable), a mouse, a way of connecting headphones and other peripheral devices. The printer went away - it's now accessible as service. Most things are.

That phone is now your stereo, your TV (and/or its controller), your GPS, your music player, your compass, your to-do list, your rolodex, your clock and calendar (and day planner), your blood pressure gauge, flashlight, concierge, restaurant menu, ledger, notebook, radio, geiger counter, and so on. Much of this essay was written on a smart phone, using a Bluetooth keyboard. Office supply companies are going out of business because most people no longer need anything sold there. Chatbots such as Siri or Cortana are becoming "companions" for autistic children, and Siri recently ended up "starring" as a voice actor for a recent movie (the Batman Lego Movie).

Smart cars will ultimately reduce both the number of cars produced and the number of cars bought. Mass customization is already taking hold in the auto industry, building a template, then print as much as you can before going out to your supply chain. You go online, look at a car, then customize it on your phone or laptop, acquire and get approved for the loan during the process, and a day later, it drives itself to your house. Fewer cars need to be produced, fewer cars end up in the fleet or used car lot gathering dust. You need a smaller investment of stock at the front end, hence a smaller overall investment in starting a car company. The economy shrinks, and single big investors hoping for a big payoff get replaced by lots of smaller investors hoping to solve problems or meet needs specific to them.

There is a pattern that is emerging here about the Solar Economy. An economy, any economy, is the means by which needs are fulfilled by the most expeditious means ossible. This is Mazlow's pyramid in its rawest form. People need to be fed, need to be housed, need to be kept relatively warm and safe from harm. Beyond that, they need a purpose, something that moves them to go beyond the lowest tier of that pyramid.

The third industrial era worked on the principal that jobs were things handed out by employers in response to needs. Beyond a certain income, most people in the uppermost income brackets do not have jobs. They may have titles, but in general their wealth comes primarily from gaming the system, and taking advantage of their wealth to invest in virtualizations of companies called stocks or bonds. Indeed, a company's valuation can change overnight; a company could gain millions of dollars overnight over a favorable review or a key test being passed, or could lose that same sum because of scandal or the failure of that test. In reality, this plays very little difference in the actual value that the company may provide.

Consider for the moment Twitter. Twitter does not generate much in the way of revenue; indeed, every attempt to monetize it has brought a fairly strong counter-reaction by its millions of users. Yet Twitter undeniably provides value. Wikipedia works the same way, but also provides a hint about what fourth industrial economies look like. Wikipedia is crowd-sourced not only in its creation but also in its funding. Every month this author sends a check for $25 to help pay for Wikipedia. Patreon and kickstarter are similar. Youtube has become a huge boon to performers, once they got past the realization that their agents and recording companies were imposing a significant surcharge in marketing that they could fill themselves.

Significantly, most of that money is not physical; it's electronic, chits of credit. This is where blockchain and bitcoin come into play. Right now, bitcoin is playing in many of the same spaces as more traditional money, but has an advantage that no other currency does - it only grows slowly, and it is unaffected by policy. It is also fundamentally accountable while being private, and best of all, it is non-destructive. This is important because you do need a way to interface between an electronic and a physical currency, at least for a while.

The Solar economy is still an economy predicated upon the movement of atoms rather than bits, but at a reduced scale. Your need for supply chains drops considerably when you can manufacture those intermediate components in a just as needed basis. Your need for crop production diminishes when you can farm even in urban environments, and more can create texture proteins, fats and carbohydrates synthetically using bioengineering and 3D printing - yes, the first few generations of such will likely be only vaguely palatable, but it is likely that within twenty years we will be seeing synthetic beef that is indistinguishable from beef from live cows. You still need raw materials, but you need fewer of them, and you throw away far less. This means less need for investment, and lower hurdles to achieve crowd-sourced food supplies.

This doesn't replace capitalism, but it does do a lot to reduce speculation, which is the most corrosive aspect of capitalism. Speculation actually exists as a drag to the economy, because it ties up capital in non-performing activity (where non-performing here means moving pots of money around rather than providing tangible physical benefit), and in general chases those investments that will return the largest financial dividend to investors rather than those that are most needed or wanted overall.

It also does a huge amount to reduce wasted taxes. Most taxes go for things that the majority of people may not actually want or need. Today, most people, if asked, would prefer their taxes to go to better school systems, improved roads and bridges, a better (but not overbearing) police presence, hospitals, sanitation systems, parks, research. Most would rather not be funding multibillion dollar weapon systems (though a surprising amount might). By creating funding buckets and categories, you end up with a system where you balance between popular allocation and the ability of decision makers as to how best to optimize priorities within those buckets.

So this leads to the big question? How do people get the basics? This is where there's disagreement, though most are moving towards some form of Basic Living Income, or BLI. The following is just one potential implementation:

The BLI would be a regular, monthly renewable floor of income that could be adjusted by region, probably managed at the state (or more properly regional) level. It covers an estimate for living expenses per person (with children and the elderly getting a higher amount). It is also, unlike current welfare systems, not tied to income. This would also be separate from healthcare and education, each of which would also be paid up to a specific level. There would also be a secondary tier of "tax" spending, in which each person has a certain fixed amount of credit that they can allocate to categories of government spending.

Finally, on top of that, you have private, government and crowd-sourced jobs. People can create corporations to fill a certain need and can solicit crowd-sourced funds to fund these. Profits go to the participants (which means that if you want to make money from a company, you would have to provide some sweat equity into it as well). You can be a broker, but brokerages are taxed. Corporations are also taxed, in proportion to the overall profits that are made, and are taxed on their own waste production.

IP Protections can be applied, but different industries would have different periods of exemption, most not exceeding ten years. Taxes are made on purchases, not income, and are collected at the time of the transaction. Crowdsourcing productions result in reduced costs for crowd-sourcers for physical items. Tuition (and accreditation) is free, but physical facility costs are not (though schools, up to and including universities would have to make all classes accessible). Healthcare is single payer and compulsary.

Corporations can be formed to do anything from building cars to building roads to providing educational services. Tiered services are possible - this is simply another form of crowdfunding. A person can be a corporation (this would have a huge effect upon the economy, by itself).

There's more along these lines, but in the end, what emerges out of this is an economy that is generally more efficient, more sustainable, and more productive. Automation in general handles more and more of those tasks that are simply not of value for a person to do, while enhancing the capabilities of people to do their own jobs and contribute meaningfully.

One way of putting this - do people like flipping burgers? In some cases yes - cooking is one of those activities that many people enjoy doing, and take pride in doing well. Working a fast food job for minimum wage because you have to pay the rent with something? That's a different issue. In general, in those places where the fourth industrial age is most prevalent, the rule has been for greater job growth, partially because there is more latitude for doing meaningful work that adds tangible value. Health care costs are down, because more people can get real coverage (and costs can be reined in while limiting the power of insurance companies) and the quality of life in general is higher.

It also means that people can explore entrepreneurial behavior outside of traditional circles. A weapon's smith or costumer provides value in a medieval recreation group, and by removing the overall worry about making ends meet can actually build a successful business in a global market. Writers are actually beginning to make a real living again, but would be able to do so even more if they could concentrate on their writing rather than taking a nine to five job to pay the bills, people could volunteer more, and charitable organizations could better support their core missions.

What of those left behind? These actually fall into two distinct camps. The first are those whose employment is fundamentally tied to third age activities. There will still be a need for petroleum engineers and drillmen and explosives experts. The third age economy still underpins the fourth and likely will for many years to come, though that will diminish over time. Automobile production will decline somewhat in the solar era, but not so much that one can't get a job in that field.

What changes, though, are individual skills. To put together an autonomous electric vehicle requires a number of different skills than running a production line in a more traditional plant. These skills can be learned, but they require retraining, and they mean that skills that have been learned are not directly applicable. That's the price for admission to fourth industrial era jobs. Expecting that the skills you learned from thirty years ago will see you through the rest of your life is unrealistic at the best of times, and is even more true now. It also may mean relocating to where the jobs are. This is a harder barrier to cross, and it is one that many currently in the fourth economy know well.

This hits older workers disproportionately, especially those who've already entered into management. There are simply fewer management jobs, and that trend will continue as organizations become more automated, as critical business functions become subsumed in online "* as a service" platforms, and as work-forces become more distributed.

There are also fewer line jobs, and that too will continue. Mass production itself has become mass customization, which puts more reliance upon design and technical acumen and less on mechanical skills. Indeed, contemporary manufacturing in almost any sector looks far more like any other computer driven activity than it does factory work.

This is even true in areas such as agriculture and packing. Traditional manufacturing can (and has for a while) been used in fast food production to take protein slurry and generate food in just about any shape (that is in essence what boneless chicken really is). Most food producers now are hiring experts in food synthesis to shape taste, texture and color such slurries, and with the advent of synthetic production and 3D printing and scaffolding, the whole pre-industry of growing animals for meat production will go away.

Expectations are shifting as a consequence. If you grew up eating real meat, the idea of eating synthetic is likely revolting. If you're a millennial, it's likely to be less of an issue, and within the next fifteen years or so, its likely that a generation will grow up that have never eaten butchered beef or chicken. And this is the point with most of the shift.

The Fourth Industrial Era is already well underway, and will continue, regardless of any efforts on the part of a retrenchent government to stop it. The primary opposition to such a transition that have emerged have come from areas where companies have left because there has been no investment in education by government or by companies, and where there is very little to actually keep the young from leaving. When you look at the migration paths of Millennials - those thirty five and under, most are moving out of these areas precisely because the governments in those areas have done nothing to strengthen that work force. Companies there are instead moving to where the Millennials are, seeking young, adaptable, skilled and still relatively inexpensive labor.

Automation plays a part, but the automation isn't happening magically, nor is it by itself a panacea for replacing skilled labor. That day may come, but human beings are remarkably inventive in finding ways to stay relevant. Given this, it's perhaps more realistic to look at those who are fighting the transition as those who are too heavily invested in a fading age, living in a past that, in reality, never existed. These are not the workers, but the politicians and third era robber barons, the ones who seek to keep things the way they are, even as they move further and further behind technologically.

My expectation is that the United States in particular will become three countries in practice - not South vs North, but Inner vs. Coastal, GenXers and Millennials vs. Boomers and and more to the point of this article, Petroleum era vs Solar. I say three countries because the East and West Coast have been moving more or less in synch technologically, but culturally they have been drifting apart - without the middle to glue them together, they will eventually becoming distinct nations.

This has been a particularly difficult conversation to have right now. We've created echo chambers that reinforce our beliefs, not just on the Internet, but between the Internet and third era broadcast media. There is no longer agreement about what constitutes authority and truth, which is the foundation upon which a culture exists. That may be another side-effect of the move to the Solar economy - it has created a cultural divide that is insurmountable, and caused a two hundred and forty year Republic to finally, irreparably, shatter.

Is it possible to repair this divide? I don't know. It would likely involve either the country as a whole accepting that we have transitioned, or giving up computers, the Internet, the array of technological and medical marvels that have taken place since the 1960s. I just don't see that happening.

One final point. I’m not trying here to sugarcoat this vision. It has its downsides, some significant. I think we’ve passed the tipping point where this future is inevitable some time back, maybe as much as by forty years. Human social behavior tends to change in the aggregate only very slowly, but once a deep trends has begun, it will play out regardless of the amount of opposition put up against it, until it has run its course.

I believe, though, that we need to look beyond the definition of jobs, especially once those get decoupled from the need to get beyond the basics, and concentrate on the fact that the fourth industrial age is far less destructive over all than the third.

Our ocean biospheres are dying at a terrifying rate. We are witnessing the re-emergence of land from under ice that hasn’t seen the light of day in millions of years. We have gone from less than three billion people on this planet a century ago to seven billion today, with demographic trends suggesting that we will hit ten billion people by 2050. The planet can support that population because it currently does, but there are clear indications that we are straining the ability of the planet at current levels let alone where those levels will be in thirty years.

To address these, we need to change our economy, need to be better at being more efficient with our energy usage and need to cut our extreme dependency upon non-renewable resources. We need to better account for our waste production as well, capturing as much of that which can be recycled back into the economy. It is here, especially, where automation proves to be beneficial, where science proves to be beneficial.

I personally do not think that the US will end up being the leader in this. We’ve ceded that authority, likely forever. Instead, we will continue to see a cult of ignorance and hypocracy at work trying to justify a status quo that increasingly does not make sense for most of its participants, where you’ll see islands of the archipelago doing everything they can to prepare, to push forward.

The stakes are simple — survival. Those islands in theory will become islands in reality as sea levels continue to rise (and they are, quite demonstrably rising), with at least half of this country living within a three meter rise in sea levels. We will see storms of increasing severity, will see droughts in the midwest, inland deep south and the plains (and in the far west as well), droughts that will only hasten things such as the depletion of potassium in the soil so necessary for plants to grow. By 2050, the likelihood is very high that the farm-belt will be like Oklahoma or western Kansas — sere, prone to dust storms, and unable to support the growing of food. Water will be at a premium.

We either figure out how to make the fourth industrial work, or we are at risk of reverting to the first.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest