Comments

- No comments found

The US environmental movement has deep historical roots.

As an example, Yellowstone National Park was created by an act of Congress and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1872.

However, the modern era of US environmental policy making is usually dated to a wave of federal laws passed in the early 1970s. Joseph S. Shapiro offers a discussion of “Pollution Trends and US Environmental Policy: Lessons from the Past Half Century” (Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, Winter 2022, 16:1, pp. 42-61).

The basic story is one of policy success: that is, a number of major environmental pollutants have been dramatically reduced, and environmental policy is a prominent cause of those reductions. Shapiro describes some of the trends in environmental pollutants this way:

Indeed, the data indicate that ambient concentrations of some air pollutants have fallen dramatically in recent decades. Between 1980 and 2019, concentrations of carbon monoxide, lead, and sulfur dioxide each fell by more than 80 percent; there have been similar declines in particulate matter, but ground-level ozone concentrations have fallen by only a third … The most common indicators of surface water pollution have decreased substantially since the 1970s. For example, between 1972 and 2014, fecal coliforms (a measure of bacteria associated with human and animal wastes) fell by about two-thirds. Total suspended solids (a measure of the total particles suspended in water), which reflects a wide range of pollutants, fell by about a third over the same period … Data from the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) show sustained and large declines in emissions of many types of toxic pollution to water, air, and land.

Environmental data is admittedly imperfect, but the overall pattern seems clear. The main exception to this pattern of sharp declines in pollution is carbon emissions, which instead has experienced smaller and more recent declines. Shapiro writes:

These data show steady increases in US CO2 emissions through 2008, followed by a gradual decline through 2021 (US EPA 2021d). The decline that occurred immediately after 2008 was likely due to the Great Recession. However, the continued decline has more likely been due to falling US natural gas prices caused by hydraulic fracturing (fracking), which has resulted in the substitution of natural gas for coal in electricity generation

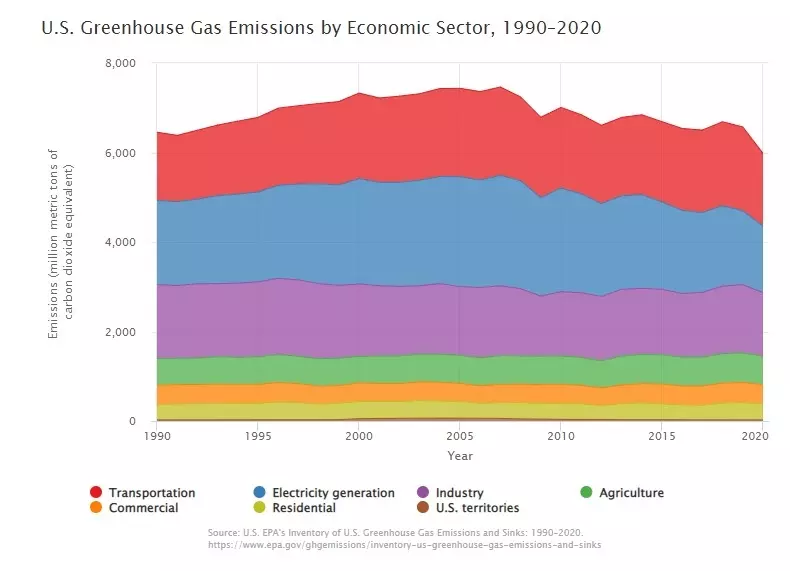

Here’s a figure mentioned by Shapiro from the Environmental Protection Agency on US carbon emissions. Overall, the figure show how US carbon emissions peaked back around 2008 and have declined since. The figure also shows that although public discussions of carbon emissions often focus on transportation (red sector) and electricity generation (blue sector), these two sectors account for only about half of US carbon emissions.

There are a number of possible reasons for the decline in US pollution that have nothing in particular to do with environmental rules. For example, the long-term shift in the US economy away from agriculture and manufacturing and toward services is, overall, less polluting. It may be that some US imports are creating pollution abroad, but reducing US pollution. It may be that overall increases in productivity–fewer inputs needed for the output–would have reduced pollution in some sectors regardless of the pollution rules. However, as Shapiro points out, if one looks at specific emitters of pollution like the US manufacturing sector, or passenger cars, “the evidence appears to support the hypothesis that environmental policy has been the dominant driver of the decrease in pollution.” I would add that construction of sewage treatment plants and rules about wastewater treatment have had important effects in cleaning up surface water, as well.

Have the reductions in pollution been worth it? Economists have sought to itemize and monetize the costs and benefits of environmental rules. The studies can be controversial, as one might expect. In particular, the costs of following an environmental rule can be relatively clear-cut, but the benefits may involve issues like putting a value on human health, or estimating changes in real estate prices (say, whether houses next to a cleaned-up river are worth more as a result), or values of improved recreation activities, or even trying to put a value on people’s preference for the environment to be cleaner.

That said, Shapiro summarizes a recent study in this way: “[O]ne recent review finds that for all [federal] regulations analyzed between 1992 and 2017, the ratio of total estimated benefits to total estimated costs was 12.4 for air pollution, 4.8 for drinking water, 3.0 for greenhouse gases, and 0.8 for surface water policy.” The area with the weakest support involves surface water policy. The issue here is that while improved drinking water has benefits for human health, the benefits of cleaner rivers and lakes are typically based on estimates of changes in real estate values and recreation.

These are averages over a variety of rules, and so it remains likely that some rules have much larger payoffs than others. But in evaluating an area of regulations as a whole, when benefits are a multiple of costs, it’s a good sign. Indeed, it suggests that tightening a number of these environmental rules–especially on air quality–would bring additional benefits.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest