Comments

- No comments found

What paths can high school students take in accumulating hard and soft skills so that they can make the transition to a career and job?

The main answer in US society is “go to college.” But for a large share of high school graduates, being told that they now need to attend several more years of classes is not what they want to hear.

Historically, a common alternative career path was that companies hired young workers who had little to offer other than energy and flexibility, and then trained and promoted those workers. Unions often played a role in advocating and supporting this training, too. But in the last few decades, it seems that a lot of companies have exited the job training business. Their general sense is that young adults aren’t likely to stay with the company, so in effect, you are training them for their next employer. Instead, better just to require that new hires already have experience.

The earn-and-learn career path tries to steer between these extremes. Yes, it involves additional learning, because that’s what 21st century jobs are like, but it seeks to have that learning take place more in the workplace than in the classroom. Also, instead of paying to learn, you get paid while learning. On the other side, firms that participate in this kind of training don’t need to take on the entire responsibility and cost of doing so.

Annelies Goger sketches this framework in “Desegregating work and learning through ‘earn-and-learn’ models” (Brookings Institution, December 9, 2020). She points out the gigantic difference in public support for higher education vs. public support for an earn-and-learn approach.

The earn-and-learn programs under the public workforce system—authorized under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA)—are underused and hard to scale. Publicly funded job training options are tiny overall compared to investments in traditional public higher education or classroom-based job training. Funding for public higher education was $385 billion in 2017-18, compared to about $14 billion for employment services and training across 43 programs. The net result is that higher education is the main provider of publicly funded training for most Americans, and most of the $14 billion for employment services and training goes to services (most of which isn’t training) for special populations such as veterans and people with disabilities.

This difference in public support is even more stark when you recognize that those with a college education are likely to end up with higher average incomes during their lives, so that we are doing more to subsidize the training of the relatively high earners of the future than we are to subsidize the training of the middle- and lower-level earners.

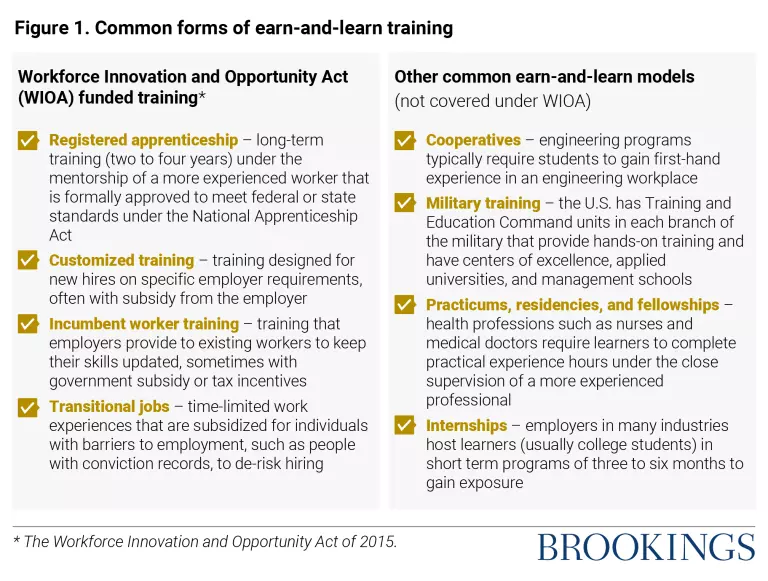

What do the earn-and-learn programs look like in practice? Here’s a graphic:

I won’t try to go through these choices one at a time: for present purposes, the salient fact is that they are all small in size. As long-time readers know, I’m a fan of a dramatic expansion of apprenticeships (for example, here, here, here, and here). But as Goger writes:

For example, the U.S. had roughly 238,000 new registered apprentices in 2018. However, if the U.S. had the same share of new apprentices per capita as Germany, we would have 2 million new apprentices per year; if we had the same share as the United Kingdom or Switzerland, that number would be 3 million.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest