Comments

- No comments found

In the big-picture long-run sense, US fertility rates haven’t changed much in recent decades.

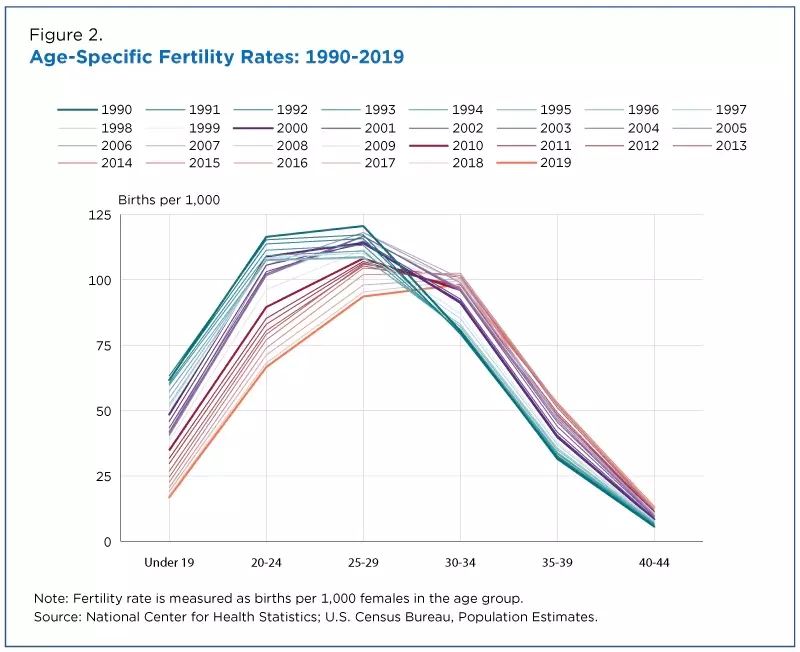

Here’s a figure from Anne Morse of the US Census Bureau in “Stable Fertility Rates 1990-2019 Mask Distinct Variations by Age” (April 6, 2022).

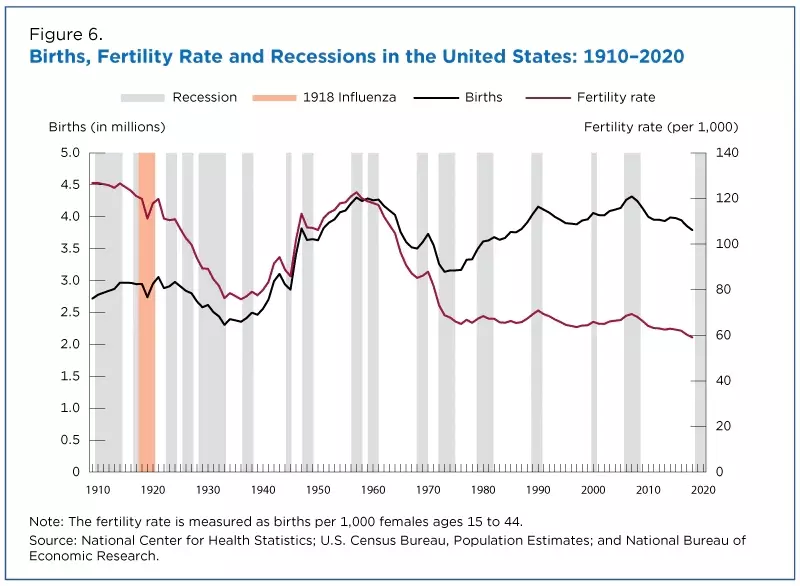

The black line shows total births in the US; the red line shows the fertility rate. For the fertility rate, you can see the plunge in US fertility rates early in the 20th century, the low fertility rates of the Great Depression in the 1930s, the jump in fertility rates in the post-World War II “baby boom,” and the following decline in fertility rates. As the figure shows, US fertility rates have been fairly stable since the 1970s, albeit with what looks like a small drop after 2008 or so and the experience of the Great Recession.

The patterns of fertility by age are also shifting. In this figure, the blue line shows patterns of fertility by age in 1990, and then each line shows the pattern in the following year up to the orange line for fertility in 2019. Birth rates for those under age 19 have been falling fairly sharply; however, birth rates for those in their late 20s and older are higher in 2019 than they were in 1990 (which for this topic really isn’t all that long ago).

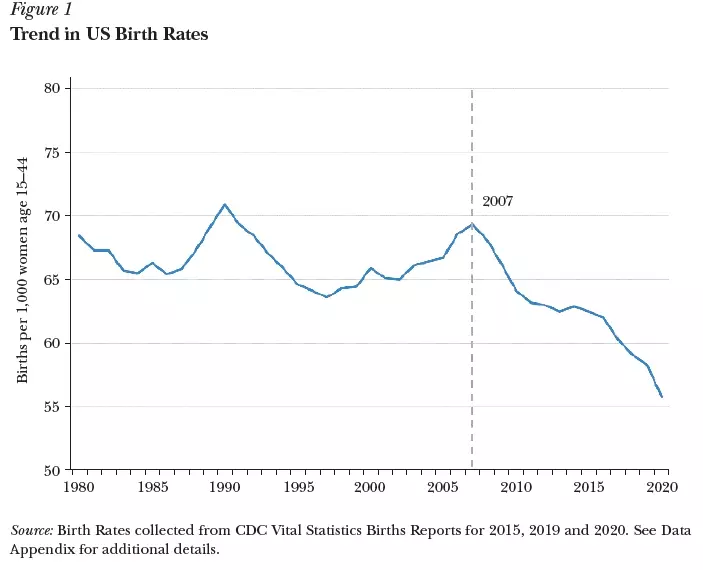

But although US fertility rates have by no means fallen off a cliff, are we seeing the beginning of a decline? Melissa S. Kearney, Phillip B. Levine, and Luke Pardue consider this topic “The Puzzle of Falling US Birth Rates since the Great Recession,” in the Winter 2022 issue of he Journal of Economic Perspectives. (Full disclosure: I’m Managing Editor of this journal. All articles in the JEP, back to the first issue, are freely available online compliments of the American Economic Association.) The authors focus in particular on birth rates from the mini-peak in 2007 up through 2020.

Part of what’s happening here is that birthrates tend to decline in recessions (as can also be seen in the longer-term figure above). But that explains less than half of the decline. The drop in 2020 is mostly not pandemic-related–after all, most of the children born in 2020 were conceived before the pandemic started. But pandemic also tend to reduce birthrates (as shown in the top figure with regard to the influenza epidemic of 1919), so birthrates are likely to drop lower in 2021 and this year.

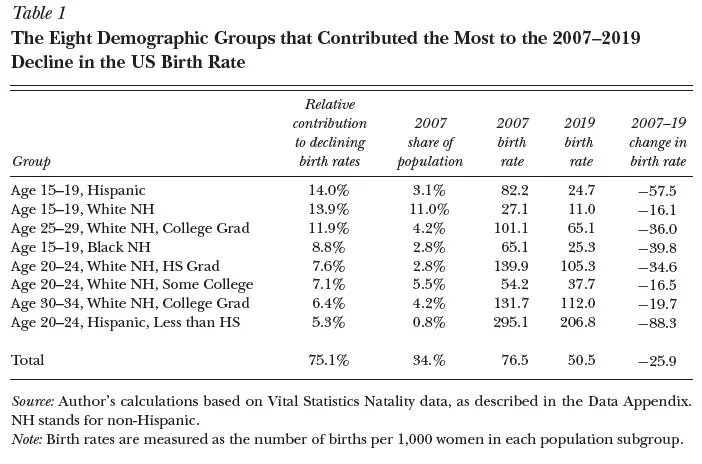

One way to get some insight into the patterns here is to divide up the groups that contributed to the decline in US birth rates by age, education, and ethnicity. When Kearney, Levine, and Pardue do this, here’s what they find:

Overall, three-quarters of the fall in birth rates can be attributed to these eight groups. Three of the four biggest drops are for those in the age 15-19 bracket–which should probably be considered as overall good news. Also, four of the eight biggest drops are for white non-Hispanics of various education levels.

One factor here seems to be that birth rates for Hispanic women rose in the early 2000s and then fell. Morse of the Census Bureau puts it this way: “While fertility rates broadly declined in the United States from 1990-2019, there was a mini baby boom in the early 2000s. This increase was driven by foreign-born Hispanic women. This mini baby boom to foreign-born Hispanics ended in 2007, just before the Great Recession began later that year. … It is not clear what portion of the fertility decline to foreign-born Hispanics can be attributed to the economic downturn since the decline began before the Great Recession started. This decline may partially be due to the end of the mini baby boom for foreign-born Hispanic women and a return to long-term downward fertility trend.”

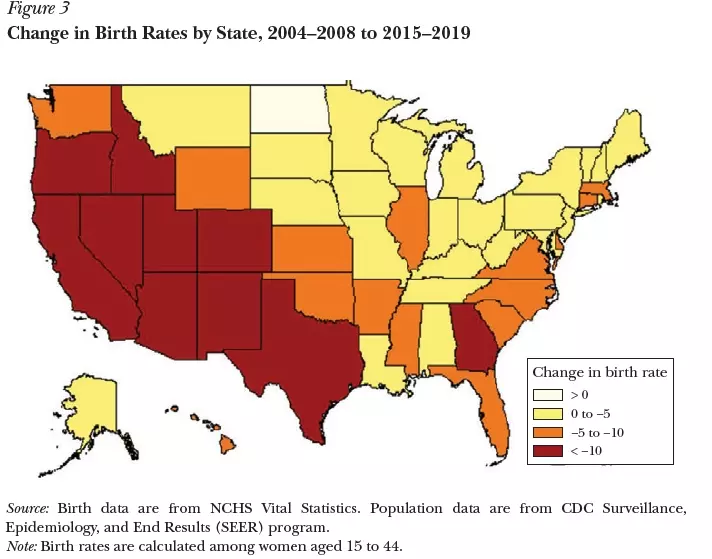

Similarly, in looking across US states, Kearney, Levine, and Pardue find that the states with the biggest drops in birth rates tend to be in the southwest, where Hispanic populations are generally higher.

Kearney, Levine, and Pardue argue that perhaps the most plausible overall explanation for the fall in birthrates is also the simplest: younger cohorts of women are growing up with a different idea of what they want from life.

It is unlikely that career aspirations or parenting norms changed exactly in or around 2007. Note, though, that women who grew up in the 1990s were the daughters of the 1970s generation and women who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s were daughters of the 1950s and 1960s generation. It seems plausible that these more recent cohorts of women were likely to be raised with stronger expectations of having life pursuits outside their roles as wives and mothers. It also seems likely that the cohorts of young adults who grew up primarily in the 1990s or later—and reached prime childbearing years around and post 2007—experienced more intensive parenting from their own parents than those who grew up primarily in the 1970s and 1980s. They would have a different idea about what parenting involves. We speculate that these differences in formed aspirations and childhood experiences could potentially explain why more recent cohorts of young women are having fewer children than previous cohorts.

However, it’s also interesting that US women are having fewer children than they say, in survey data, that they would ideally desire.

Some nationally representative surveys ask women about their expectations or desires for childbearing. On this point, the number of children that women report wanting to have has been dropping slightly. Hartnett and Gemmill (2020) report that data from the 2006–2017 National Survey of Family Growth shows that the total number of children women intend to have declined (from 2.26 in 2006–2010 to 2.16 children in 2013–2017) and that the proportion of women intending to remain childless increased slightly. Women also tend to end up having fewer children than they say would be ideal and that gap has been growing(Stone 2021). One interpretation of this discrepancy is that it offers prima facie evidence that constraints or costs are playing a role in depressing birth rates. An alternative interpretation is that women report they want, say, two or three children, but when faced with actual trade-offs associated with having more children, they choose differently.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest