Comments

- No comments found

Economic development at the national level has followed a fairly consistent path for centuries, with some local variations.

A less developed country starts off with most of its workers in agriculture. It first shifts to low-wage manufacturing, then builds the skills and capabilities for high-wage manufacturing, and from there moves into service and knowledge industries.

But there are real concerns over whether this approach can work in the 21st century economy, at least for more than a handful of countries. In many industries, robots can take over manufacturing jobs. For sophisticated manufacturing, a large share of the economic benefit goes to the designers, scientists, and engineers behind the innovation–or to the company that owns the intellectual property–not to the workers on the assembly line. Thus, development economists have been struggling with the question: Can at least some developing countries use digital technologies and the connectedness of the internet to skip past the manufacturing stage and go straight to exports of services in global markets?

In a joint report, the World Trade Organization and the World Bank tackle this question in “Trade in services for development: Fostering sustainable growth and economic diversification” (2023).

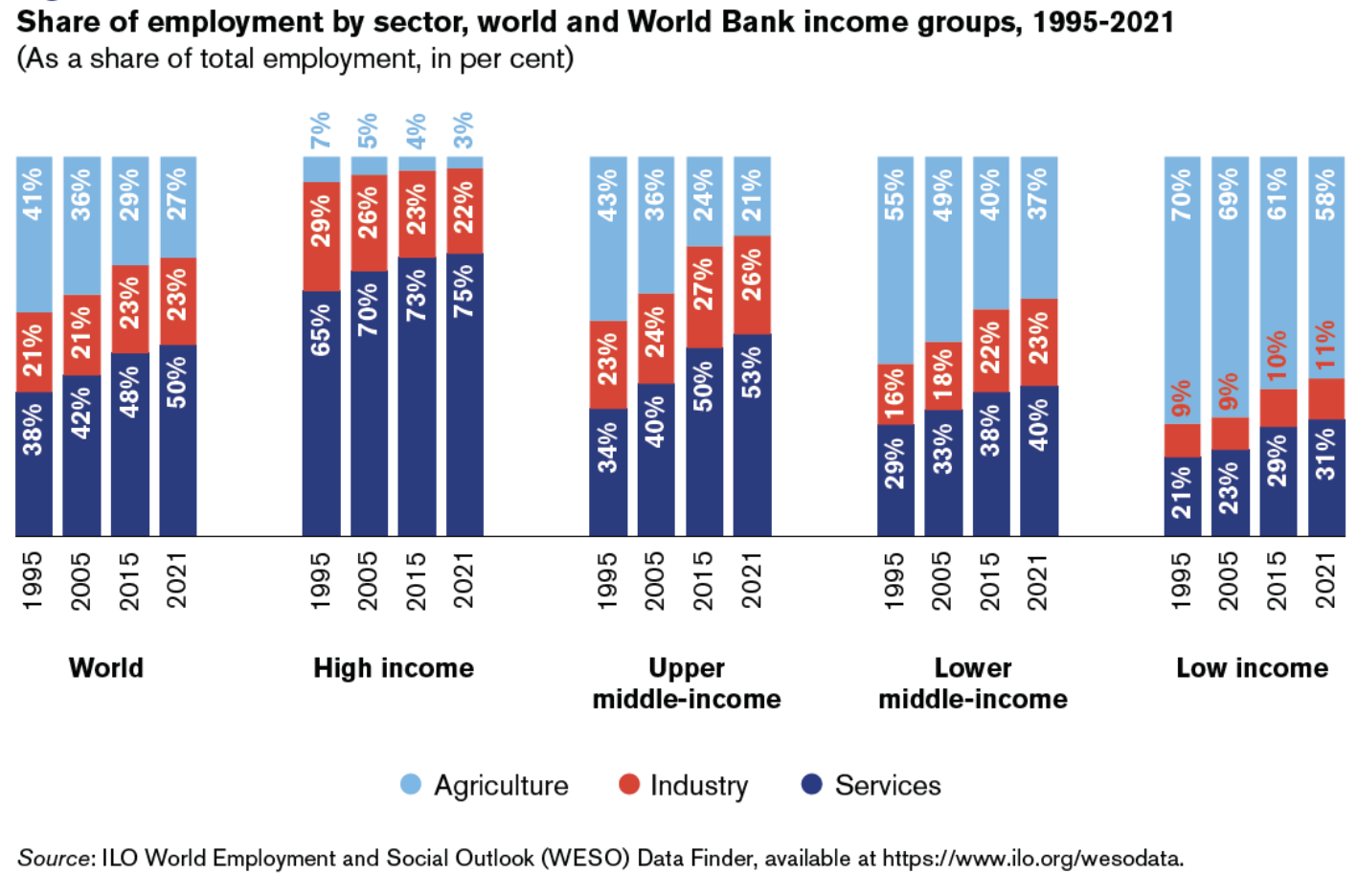

Here’s a figure that helps to illustrate the standard development pattern. Notice that high-income countries have the lowest share of jobs in agriculture, while low-income countries have the highest share. Everywhere, jobs in agriculture are decreasing over time. But the biggest sector for job gains is not industry–which has actually been shrinking as a share of jobs in high-income countries–but rather jobs in services.

The report makes case for optimism about the possibilities of developing countries using trade in services as an engine for economic growth. Here’s some background information:

Services trade has been the most dynamic component of world trade for the last 15 years. Such dynamism provides developing and least-developed economies significant opportunities for export-led growth, economic diversification, inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and integration into global value chains.

Services trade promotes greater inclusiveness, particularly for female and young workers and entrepreneurs as well as micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). In 2021, 59 per cent of employed women worked in the services sector, and 9 out of 10 services firms were MSMEs. Today, the services sector generates half of employment worldwide and two-thirds of global GDP – more than agriculture and industry combined. These changes in the structure of the global economy challenge long-held perceptions of services as a less desirable path to economic growth and development compared to manufacturing. …Fuelled by advances in information and communications technologies (ICT), exports of commercial services almost tripled between 2005 and 2022, with exports of digitally delivered services experiencing the fastest growth, increasing almost four-fold. During the same period, developing economies accounted for an increasing share of global services trade, as least-developed economies’ exports of commercial services grew more than four-fold between 2005 and 2002, while those of other developing economies more than tripled. The expansion of developing economies’ exports is increasingly tied to services supplied across borders through digital means. And developing economies account for an increasing share of non-traditional service exports.

What exactly is meant by “services” in this context? It was conventional wisdom for some time that international trade in services might be difficult, because lot of services are locally provided. For example, you can’t outsource the taxicabs in one city to be provided by drivers in another city. But for that taxicab company, it is possible to do record-keeping, back-office services, and even answering calls with a base in another country. This form of international trade in services is delivered over the web. However, tourism is also counted as a “services export:” for example, when a US tourist visits Kenya, services sold in Kenya are being provided to US buyers.

In the future, services including health care and education may be divided up, with some portion of those services being provided across national borders. If you are using “telemedicine” to contact a health care provider on-line, they don’t need to be residing in your country. If you are willing to travel to a provider in a different location for your medical care procedure, then that provider can be outside the country as well. Here’s a comment from the report on “medical tourism:”

Medical and wellness tourism has expanded significantly in recent decades, propelled by improved telecommunications and transport services. Countries such as Brazil, Cuba, India, Jordan, Malaysia, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates have become major medical hubs, receiving foreign

patients from both developed and developing countries. For example, India has become a popular destination for medical travel, and hosted around 3.5 million foreign patients from 2009 to 2019. Foreign patients from developed countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, as well as from developing countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka, go to India in search of less

costly, high-quality treatment.Thailand is another popular destination for medical tourism. It has developed a large medical tourism sector geared towards foreign patients, with 61 hospitals bearing the Gold Seal of Approval from the Joint Commission International, an organization which assesses hospital standards around the world. In 2019, Thailand received 172,265 international medical tourists, according to estimates by its National Statistical Office. In order to mitigate the internal brain drain risk caused by the expansion of an industry geared towards attracting international tourists, doctors and nurses are required to serve three years in the public system, including in rural areas, prior to working in private hospitals, in return for public funding of their education. The government has also increased the salaries of physicians, nurses and dentists in all community hospitals to encourage these professionals to stay in the public health sector and maintain the quality of public healthcare services.

I do not yet have a good sense as to the role that exports of services can play in broad-based economic development. In part, my problem is that the general area of “services” is almost inconceivably broad, and understanding what kinds of services exports might work well for countries with different locations and strengths is a complex problem. But I do suspect that the old-style route to development via low-wage manufacturing is not as workable as it used to be. In addition, the path to economic development for countries with lower per-capita GDP has typically involved finding ways to trade with countries with higher per-capita GDP.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest