Comments

- No comments found

Claudia Goldin has been awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2023 “for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes.”

Goldin does economic history, but as a different economic historian once said to me: “History starts yesterday.” In a similar spirit, Goldin’s work (with a primarily US focus) ranges across centuries and decades, but also focuses directly on 21st century patterns. As usual, the Nobel committee has published two descriptions of Goldin’s work, which they designate as the “Popular Science Background” (7 pages long) and the “Scientific Background” (38 pages long). With those overviews easily available, I’ll just touch on three themes here.

First, real economic historians like Goldin do serious archival work, often uncovering previously unstudied data or looking at common data in a different way. For one of many examples, Goldin noticed that in the data on “occupations,” married women often had “wife” listed as their occupation. In the past, this designation had been taken to mean that women weren’t working as part of the paid labor force. As the “Scientific Background” report notes:

One of her main contributions concerns the under-counting and omission of female workers, especially in the period before 1940. During this time, it was, for example, common to simply list “wife” in the census when referring to married women. In a modern context, this would imply nonparticipation in the labor market. Yet many married women who were recorded as wives actually engaged in what we would now consider labor market activity. The wife of a small farmer or farm laborer almost certainly worked together with her husband on the farm. The wives of boarding house keepers, and probably many other small business owners, worked in their husband’s business. Combining data from income reports, time budget surveys and census data, Goldin showed that adjusting for the undercounting of women in the agricultural sector raised the female labor force participation rate by almost 7 percentage points in 1890. Adjusting for undercounting in other sectors (mainly boarding house keepers and manufacturing workers) adds an additional 3 percentage points. Most of the adjustments apply to white married women: the corrected female participation rate of that group is five times the official census statistic (12.5% versus 2.5%). The labor force participation rate for married women in 1890, therefore, is similar to that observed in 1940. … Goldin (1990) provided evidence that the undercounting problem is likely greater further back in time, since the occupations of women were not collected in most pre-1890 censuses.

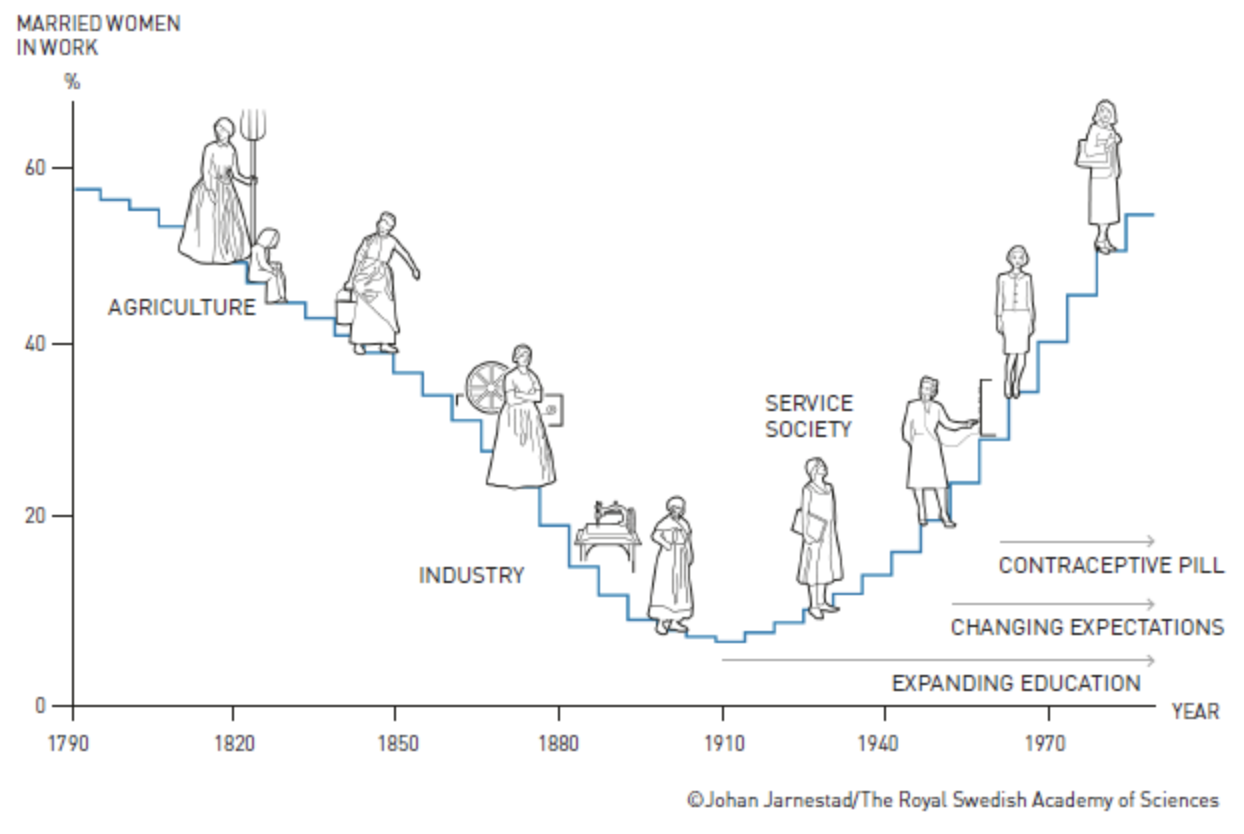

Digging into the alternative US data sources going back a couple of centuries offers a number of insights, but one big takeaways is that the share of women producing output for sale in the market had a U-shape during US economic history: that is, very high levels back around 1800 when many women worked in agriculture, a declining share with the shift from agriculture to industry in the 19th century, and then a rising share with the transition to service industries starting about 1920.

Second, a substantial advantage of a historical approach is that it allows seeking to understand big institutional or technological changes. In a substantial share of modern economic research, the focus is on a particular theoretical model or a particular set of data. In contrast, work by economic historians is often focused on a bigger question, using theory and data as needed to illuminate it. Here are a few examples:

For example, one reason why women were not represented in the paid labor force in the early decades of the 20th century was the growing adoption of “marriage bars,” laws and rules which blocked women from staying in many jobs after they married. In other words, the role of women in the labor force was not just a matter of social convention or choices made within families, but enforced by law. The Nobel committee again:

In the 19th century … women almost uniformly left the labor force upon marriage (and were married for the vast majority of their adult lives). The social stigma and norms driving this exit were formalized into explicit regulations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. So-called marriage bars, which explicitly prohibited the hiring or employment of married women, were introduced. Goldin (1988, 1990) documented two kinds of marriage bars. “Hire bars” banned hiring married women but permitted firms to retain women who got married while already employed.

“Retain bars” were more restrictive and required the firing of women upon marriage. The use of the marriage bars peaked after the Great Depression and were particularly common for positions as teachers and clerical workers. In 1942, 87% of school districts had hired bars and 70% had retained bars. Marriage bars were also more prevalent in large firms. A 1930s survey of firms found that 35-40% of women worked in firms that would not hire a married woman.

For an example of a major technological change, Goldin (along with Larry Katz) considered how the contraceptive pill affected labor market outcomes for women. The Nobel committee wrote:

In the US, the first oral contraceptive was approved in 1960 and made available to married women. But until the end of the 1960s, access was limited for young unmarried women. Single women below the (state-specific) age of majority needed parental consent to access the pill. In the early 1970s, many states reduced the age of majority from 21 to 18 and passed laws increasing access to family planning and contraception without parental consent. Thus, there is state-by-time variation in access to oral contraceptives for young single women. Importantly, the changes in the age of majority were not actually driven by family planning concerns but rather by a desire to reduce the age of conscription for the Vietnam War.

An ongoing theme in Goldin’s work is how changes for broad groups, like “women,” often seem to happen for a cohort (that is, a group born at about the same time) where shifts in conditions combine to change expectations and also behavior.

Finally, I’ll point to one of Goldin’s contributions to women and the labor market in the 21st century. An overall pay gap between men and women remains. There’s solid research that much of the remaining pay gap is a “parental” gap, reflecting the fact that women end up doing more childcare than men. As a result, women find themselves less likely to have an uninterrupted career path, and more likely to end up in jobs that offer more work/life balance.

Goldin pushed this line of thought further. She found that “the majority of the current earnings gap [between men and women] comes from earnings differences within rather than between occupations.” In particular, the pattern in a number of occupations is that those who are most highly paid work long hours: that is, in many occupations the pay per hour is higher for someone working a 50-60 hour week than for someone working a 35-40 hour week or a 20-25 hour week.

As the Nobel committee writes: “[W]omen receive a wage penalty for demanding a job flexible enough to be the on-call parent. Men, on the other hand, receive a premium for being flexible enough to be the on-call employee, i.e., constantly available to meet the needs of an employer and/or client. In jobs where such “face time” is valued, one employee cannot easily substitute for another and part-time work is hard to implement. Nonlinearities in wages emerge as a result: workers willing to work many hours are rewarded with a higher wage.”

Thus, certain jobs like pharmacists have a high level of workplace flexibility, and the wage gap per hour between men and women is relatively low. An ongoing subject for research is whether it is possible to have greater flexibility on hours, perhaps by pushing back on expectations about how the fast-track and high-paid workers must also be those who work the longest hours. But it may be that greater workplace flexibility holds one of the secrets to further reductions in the male/female wage gap.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest