Comments

- No comments found

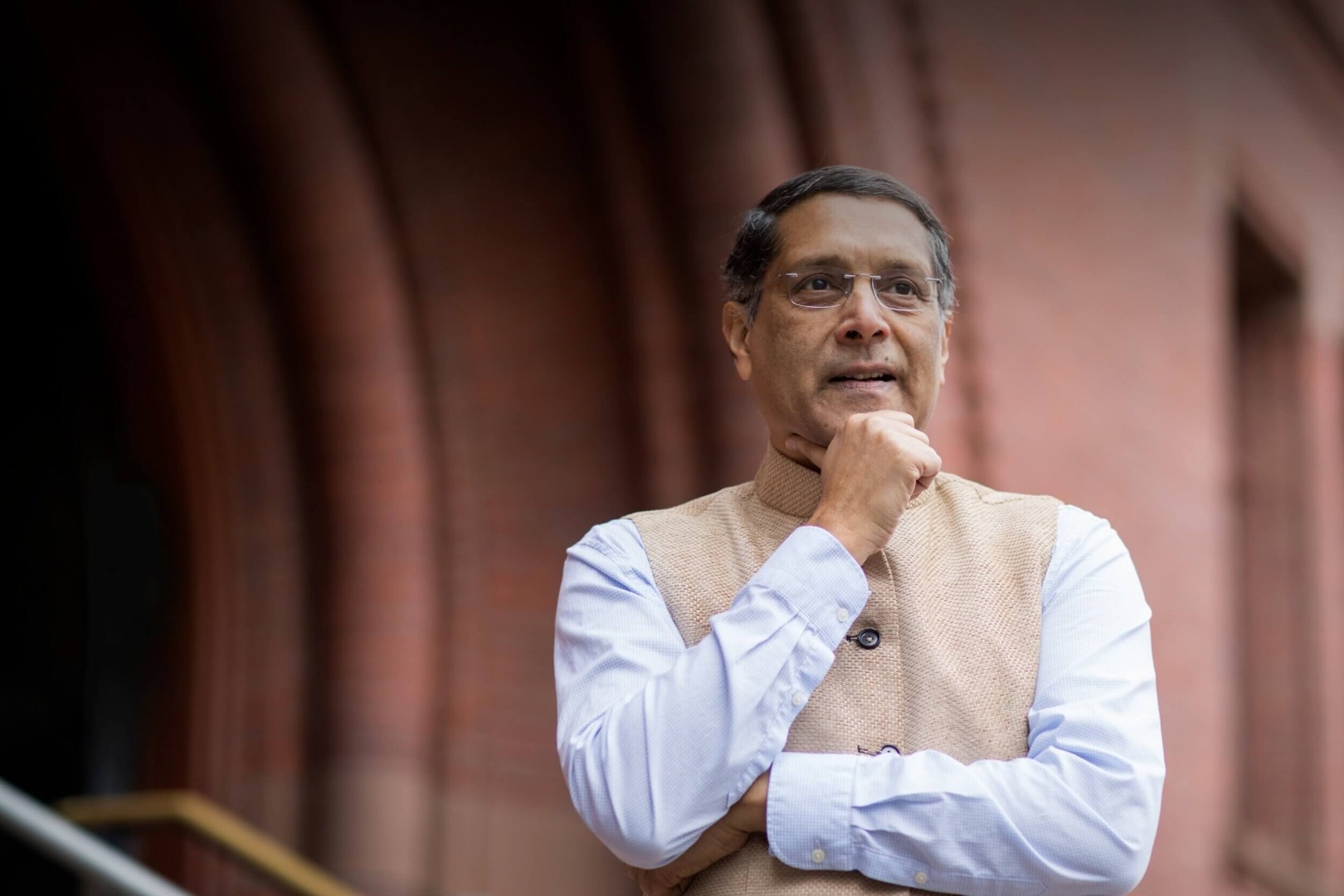

Noah Smith serves as interlocutor in “Interview: Arvind Subramanian, former Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India” (Noahpinion, April 1, 2022).

The interview is subtitled “Everything you wanted to know about India’s economy,” and it makes a strong bid to fulfill that promise. I was of course very pleased that Subramanian refers to the papers published in the Winter 2020 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives (where I work as Managing Editor) in a “Symposium on the Economics of India”:

“Dynamism with Incommensurate Development: The Distinctive Indian Model,” by Rohit Lamba and Arvind Subramanian (pp. 3-30)

“Why Does the Indian State Both Fail and Succeed?,” by Devesh Kapur (pp. 31-54)

“The Great Indian Demonetization,” by Amartya Lahiri (pp. 55-74)

Here are some tidbits from Smith’s interview with Subramanian, but the interview itself goes into greater depth. I’ll start with Subramanian’s overview of India’s economic development in recent decades.

India had more than 3 decades of really rapid growth beginning, late 1970s-early 1980s. Per capita GDP growth averaged close to 4.5 percent and as I wrote in a JEP paper (co-authored with Rohit Lamba: https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.34.1.3), India’s dynamism was quite remarkable by cross-country standards. Poverty rates declined, access to goods and services increased sharply, public infrastructure improved. And dynamism was especially marked for close to a decade between 2003 and 2012 when India may have grown even faster than China. The India Brand Equity Foundation had a even coined a catchphrase—“the world’s fastest growing, free-market democracy”—as its way of encapsulating the world’s admiration, even astonishment, as India seemed to vault effortlessly from a nation mired in poverty into a modern high-tech, car-owning middle-class society. China was the world’s factory but India was going to be its back-office. That was the expectation.

In the decade after the global financial crisis (GFC), especially after 2011, growth slowed considerably. Of course, there were exogenous factors as the world economy slowed down and globalization went into retreat. But India’s growth slowdown was sharper than for other countries, reflecting India-specific factors.

Initially (2011-2014), it reflected macro-economic mismanagement, corruption and decision-making paralysis which led to the near-crisis of the 2013 Taper tantrum. Later (post-2014) it reflected the inability of the government and central bank to address India’s Twin Balance Sheet challenge: over-indebtedness of corporates and the counterpart rising NPAs in the banking system which had financed much of the infrastructure boom of the oughties. This was a classic Japan-style problem that India did not really solve (and truth be told, did not even really embrace as diagnosis). Private investment and credit growth have been virtually flat in the last decade. And export growth was weak too. … As India emerges from the pandemic, the big challenge is: how do you revive private investment and trade (the long-run engines of growth) and in a manner that creates jobs?

India has become internationally known as a supplier and competitor in information technology markets. However, an ongoing concern has been that this emphasis doesn’t do much to offer jobs for low-skilled workers, and thus is an unbalanced strategy for economic development. Here’s Subramanian:

Great strides have not just been made in physical but digital infrastructure. In 2015, I coined a term JAM which represented the coming together of financial inclusion (the J from the Hindi “Jan Dhan”), biometric identity (the A for “Aadhaar”) and telecommunications (the M for mobile). The government has used this trinity for a variety of purposes, including making direct cash transfers to the poor. In addition, a public-private partnership has created a digital, non-proprietary platform called the Unified Payment Interface (UPI) which is driving a lot of private dynamism and innovation in a number of sectors–finance, tourism, e-commerce, software solutions etc. I like to joke that India is creating unicorns roughly at the rate that it is creating chess grandmasters. While cause for cheer, this dynamism, based on skill- and technology-intensive factors of production, cannot drive structural transformation because that requires creating jobs for India’s vast, relatively less skilled labor force. And India’s job situation, especially after the pandemic, is sobering.

Which leads to your question about why India has not really managed to achieve scale in its manufacturing operations and why Indian capital is reticent in doing so. I suspect, although I am not sure, that there is again a lot of path-dependence here. For a long time under the license Raj [a term for India’s heavy-handed economic regulations in the decades before the 1980s], domestic entrepreneurship was penalized. And there was a particular aversion to size, fearing the economic and political power that large firms could wield. … So, paradoxically, labour feels vulnerable to the power exercised by large firms but equally capital does not feel protected by the state either. So, we are in a bad equilibrium that favors small over big.

How does the Russian invasion of Ukraine affect or offer opportunities for India?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has, of course, thrown up new challenges. One would expect the Indian government and business to scent significant opportunities here. One expects that responses (sanctions) to the Russian invasion will increasingly force investors to be more sensitive to the nature of political regimes where they operate, intensifying already-existing pressures to shift production out of Russia today and possibly China tomorrow. Similarly, access to foreign markets for goods exported from such regimes has also become more uncertain.

Against this background, a democratic India should be, and see itself as, more attractive to the fleeing investors. Surprisingly though, there is growing concern that India itself might be targeted in the future for similar actions by the West. The argument is that if the US can act against Iran or Venezuela or Russia for geo-strategic reasons, pretexts can always be found for freezing Indian assets in the future or raising barriers to Indian goods and services. Talk has therefore begun about indigenizing payments systems to reduce reliance on the dollar-based system, diversifying foreign exchange reserves and negotiating barter trade agreements.

Such costly deglobalizing actions would be in keeping with and even reinforce the government’s inward turn. In the last few years, India has raised tariff barriers, implemented selective industrial policy and stayed out of integration agreements, especially in dynamic Asia. Freer trade and more intensive economic engagement with the world now risk becoming serious casualties of recent developments. …

Since sanctions against Russia are raising concerns that India could be targeted in the future, the US must work toward convincing India that there is more opportunity than threat here, and that the US will help India become the hedge against the increasing unreliability of China and the Asian value chain. For example, Devesh Kapur suggests that the US could nudge/incentivize American firms to make India the next Taiwan in terms of chip/semiconductor production capability. Of course, the Indian government will have to do its bit–quite a bit–to create the appropriate regulatory environment and assure investors that the playing field will be level.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest