Comments

- No comments found

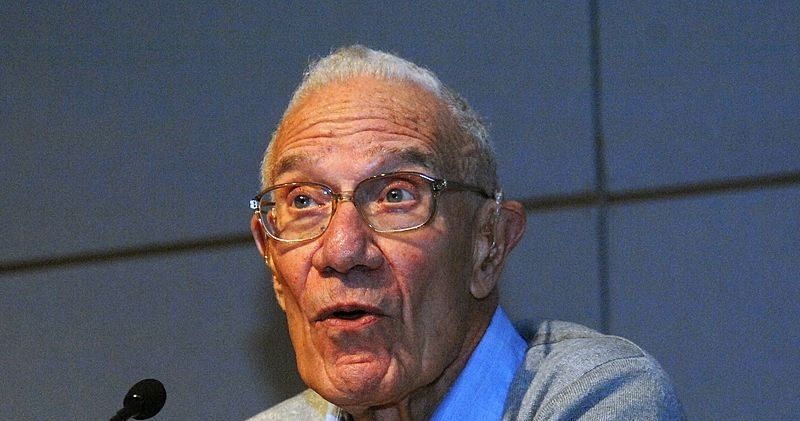

Robert Solow (Nobel ’87) is known in the economics profession for conceptualizing the broad methods of studying economic growth that are still used today.

I also think of him as one of the most gifted expositors of technical economic issues. When attending the annual conferences of the American Economic Association some years back, if I was in doubt as to which of many sessions to attend, I would just pick the one where Solow was presenting or commenting. He’s 98 now. Steven Levitt is perhaps best-known in popular culture as the author of Freakonomics (written with Steven Dubner), a 2005 book which achieved the unlikely status of being a best-seller written about academic research papers in economics. Inside the economics profession, Levitt is known as remarkably creative at coming up with empirical approaches that offer plausible (if sometimes also highly debatable) answers to a wide array of questions.

The Freakonomics best-seller morphed into a blog, additional books by Levitt and Dubner, podcasts, and interviews. Levitt recently interviewed Solow, who is one of his graduate school professors, in “Ninety-Eight Years of Economic Wisdom” (June 23, 2023, https://freakonomics.com/podcast/ninety-eight-years-of-economic-wisdom/). You can listen for an hour, or read the transcript. Here are a few of the comments from Solow that especially caught my attention:

What’s the real challenge of a zero-growth economy?

[T]here are, however, a lot of people, in the profession and outside the profession, who think that a modern, industrial, capitalist economy cannot exist without growing. … So, I want to imagine an economy like ours and think about what it would be like if it were stationary, if it were not growing and not shrinking, but just fixed at whatever size we’re talking about. The first thing that would have to be true is that the population is constant. Now, I want to make another assumption, imagine that there’s no innovation going on. There are no new products, no new industries, nothing like that. The economy is just stationary. It just repeats itself. …

I think the important thing to realize is that there is no law of economics, no principles of economics, that say that such an economy could not exist and be healthy. It’s not written anywhere that for a capitalist economy, it’s grow or die. That’s just not true. The one glitch that could occur in this stationary state is that the population wants to increase its wealth by saving, even though the economy is stationary, but we can’t let that saving get into investment because if the saving goes into building new factories, building new buildings, whatever, that moves us out of the stationary state into growth. But there’s an easy solution to that: the government satisfies the public’s wish to accumulate by running a deficit and selling them bonds and using the proceeds not to build new roads, or build new anything, but to put on beautiful fireworks displays, wonderful concerts, maybe annual dramatic festivals like the ancient Athenians. That situation could simply go on forever.

Now I come to the rub that I don’t think most people think about: this non-growing economy has, as I said, no new industries, no new products, nothing like that. That can’t be good for social mobility. What I’m afraid of is that in such an economy, the same good jobs and high status occupations would repeat themselves year after year. And the people who have those jobs would groom their children to follow in their footsteps. And that kind of society would tend to be a hereditary oligarchy. And that’s not good. So if I were trying to bring about — for the sake of warding off climate change, for the sake of preserving the environment — a non-growth economy, what I would be thinking about is how you provide for social mobility, how you provide for the children of relatively poor parents to become relatively better off while some of the children of relatively well-off parents fall in the income distribution. That’s the hard part. There’s nothing in my background to make me a specialist in how to do that, but I can see that it would be a really serious problem.

On a lesson from growing up during the Great Depression:

I was 6 years old in 1930 and I was 16-years-old in 1940. So I grew up during the whole of the Depression. Now, we were not an impoverished family. My father always had work, although he had to take jobs he didn’t like. On the other hand, from listening to my parents’ conversation, it was clear to me that the general feeling of not knowing where the next dollar is coming from, the general feeling of insecurity was the dominant thing in their conversation. That’s mostly what they talked about. One of their friends was a high school teacher of math, Mr. Ginsburg. Before the Depression, they all pitied Lou Ginsburg because he didn’t earn very much money. By the 1930s, they envied him because he had a safe and secure job. So one of the things I got out of being a Depression child was the importance of economic security. And it has made a difference because I’ve always balked at notions about the efficiency of the labor market, which amount to imposing uncertainty on workers. I think any understanding of the labor market has to take account of the fact that people really care — it’s really important to them to have a feeling of safety, of security. I still think that. It doesn’t fit so easily into standard economics textbooks, but it’s one of the things I learned from growing up in the Depression.

How Solow chose economics as an undergraduate major, upon returning from the Army after World War II:

I turned 18 in 1942 and I went back to Harvard College to start my junior year. I started at age 16. So there I am in September, maybe early October, 1942, sitting in a course on the psychology of personality. It wasn’t a bad course. I was taking it because my advisor, whom I respected a lot, told me to take it. So I’m taking this course and, like the good little boy that I am, I’m busy taking notes. And all of a sudden it hit me: I can’t sit here three days a week, taking notes on the psychology of personality, when probably the most important event of my lifetime is taking place 3,000 miles away in Europe. I just can’t do that. So, I waited till the class ended, still busily taking notes. I packed up my ballpoint pen and my notebook, and I walked out the door. I walked one block to Harvard Square. I paid my nickel and got into the subway. I Went out to Park Street, where I knew there was an Army recruiting office, and I joined the Army. I thought it was much more important to beat Hitler than to take notes in courses.

So three years later, we beat Hitler, and in 1945, I’ve got to tell Harvard College I’m going to be back in September as a junior to finish up. So I called the college office on the telephone and they said the thing to do is to get a transcript of your freshman and sophomore year, and take it to the headquarters of your major department. So I said to my wife, “I don’t have a major department. I’ve just been screwing around taking courses, mostly in the social sciences,” And I said to her, “You majored in economics, didn’t you?” And she said, “Yes I did.” I said, “Was it interesting?” And she said, “Yes, it was.” I said, “Oh, what the hell? Let’s give it a try.”

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest