Comments

- No comments found

When it comes to measuring how a minimum wage affects employment, the simple answers are wrong.

For example, one simple approach is to can look at employment before and after a minimum wage increase, but if a recession occurs along the way, surely one would not want to attribute the resulting job changes that to minimum wage increases. Also, it’s understandably easier for politicians to pass minimum wage increases when the economy is growing, but you wouldn’t want to mix up an overall climate of economic growth with the effects of a minimum wage increase, either.

Ideally, you would come up with several other and more plausible methods for isolating the effects of a minimum wage increase, so that you could compare results across these methods. What I want to do here is to describe first how such a study might be done, but not reveal the results here at the start. After all, you aren’t the sort of person who would judge the methods of a study by whether the results confirmed your previous biases, are you? No, I’m sure you’re not. Instead, you’re the kind of person who thinks first whether the method of the study makes sense, and then to the extent that it does, you will put a corresponding degree of belief on the results.

The city of Minneapolis voted in 2017 to phase in an increase in the city-wide minimum wage, starting in 2018. It would read $15/hour for large firms (employment of 100 or more) by July 2022 and $15/hour for small firms by July 2024. The city also commissioned a series of studies on the effects of this change, to be overseen by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. The most recent of these reports is “Economic Impact Evaluation of the City of Minneapolis’s Minimum Wage Ordinance,” with Loukas Karabarbounis, Jeremy Lise, and Anusha Nath as the primary investigagors (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, May 1, 2023).

The researchers have access to non-public data from the state government agency runs the unemployment insurance program, because when employers pay their unemployment insurance premiums, they need to file forms each quarter saying giving total compensation and total hours worked for each employee–which means you can easily calculate the average wage per hour. The researchers merge this with data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, carried out by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. This data includes the industry, the location by city and zip code, and if a given business establishment at a certain location is part of a firm that has establishments at other locations, too.

The authors of the Minneapolis Fed study apply two main methods for thinking about the question of the effects of a minimum wage that is being phased higher over time. I’ll try to offer a quick-and-dirty intuitive summary here.

First, they use what are called “synthetic control methods,” which look at changes over time. Specifically, they look at 37 US cities similar in size to Minneapolis, but who were not seeing a rise in their minimum wage during this time. They average together data from these cities, putting different weights on different cities, so that the weighted average of these other cities tracks the data from Minneapolis pretty well in the years leading up to 2017. The hypothesis behind this approach is that jobs and wages in the other cities tracked Minneapolis pretty well up to the passage of the minimum wage, it should have kept doing so–unless something changed.

As another example of this synthetic control method, they take the same approach but instead look only at cities inside Minnesota. Again, they weight the data from these cities so that in the lead-up to the higher minimum wage, it tracks the Minneapolis data. Again, the hypothesis is that a divergence after 2018 or so can be attributed to the higher minimum wage.

This synthetic control approach has been used in other studies, but I think it’s fair to say that it has less plausibility for this study in recent years. Compared to other cities around the country, as well as cities within Minnesota, Minneapolis experiences rioting after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. In addition, the pandemic recession may well have affected different cities in different ways: in particular, the effects in bigger cities like Minneapolis might be different from the effects in smaller cities.

But I know you’re not the kind of person who would be happy with the results of any single methodology, right? You are the kind of person who wants several different methods, so that you can compare between them.

A second approach uses “cross section” methods which do comparisons across firms and workers. In one cross-section approach, the authors look at “establishment effects” within the city of Minneapolis. Remember, they have data on industry, location, average wages, and hours worked for firms in Minneapolis. They write:

Consider a full-service restaurant, Restaurant A. It is located on the fictitious Plain Street and pays all of its workers at least 16 dollars per hour in 2017. This restaurant is not directly exposed to the increase in minimum wage, because all its workers are already earning a wage above 15 dollars. Next, consider another full-service restaurant on Plain Street, Restaurant B, which pays all its workers in 2017 an hourly wage of 7.5 dollars. Restaurant B is highly exposed to the minimum wage increase, because to continue to operate using the same workforce, it needs to increase wages for all workers.

Thus, they can compare establishments in the same industry and the same neighborhood, some of which are more affected by the higher minimum wage than others. You can compare whether the establishments that are more affected by the minimum wage adjust hours or employment by larger amounts.

However, An obvious concern here is that perhaps some firms that were previously paying low wages go under, but their workers are absorbed by firms in the same industry and neighborhood paying higher wages. Or if workers found jobs just outside the Minneapolis city boundaries, it might look as if jobs were lost, when the jobs actually just moved a few miles. Such effects needs to be taken into account.

Thus, a different cross-section approach looks at comparisons across workers. Consider workers in Minneapolis, some working for establishments that previously paid lower wages, and some that did not. The researchers can then track what happens to those workers. They can also take into account effects of being in a certain industry: say, restaurants took a bigger hit during the pandemic. Thus, the researchers can see what happened to the workers who seemed most likely to be affected by a higher minimum wage.

One final step before describing the results. Some industries have a lot of low-wage workers, so one would expect these industries to be more exposed to the effects of a higher minimum wage. Thus, the researchers do these comparisons in two ways: looking at the effects across all jobs, and looking at the effect just in the most exposed industries. In Minneapolis, the six industries where more than 30% of the workers had been making less than the new minum wage were: ” retail trade (44); administration and support (56); health care and social assistance (62); arts, entertainment, and recreation (71); accommodation and food services (72); and other services (81), which consists of repair and maintenance shops, personal and laundry services, and various civic, professional, and religious organizations.”

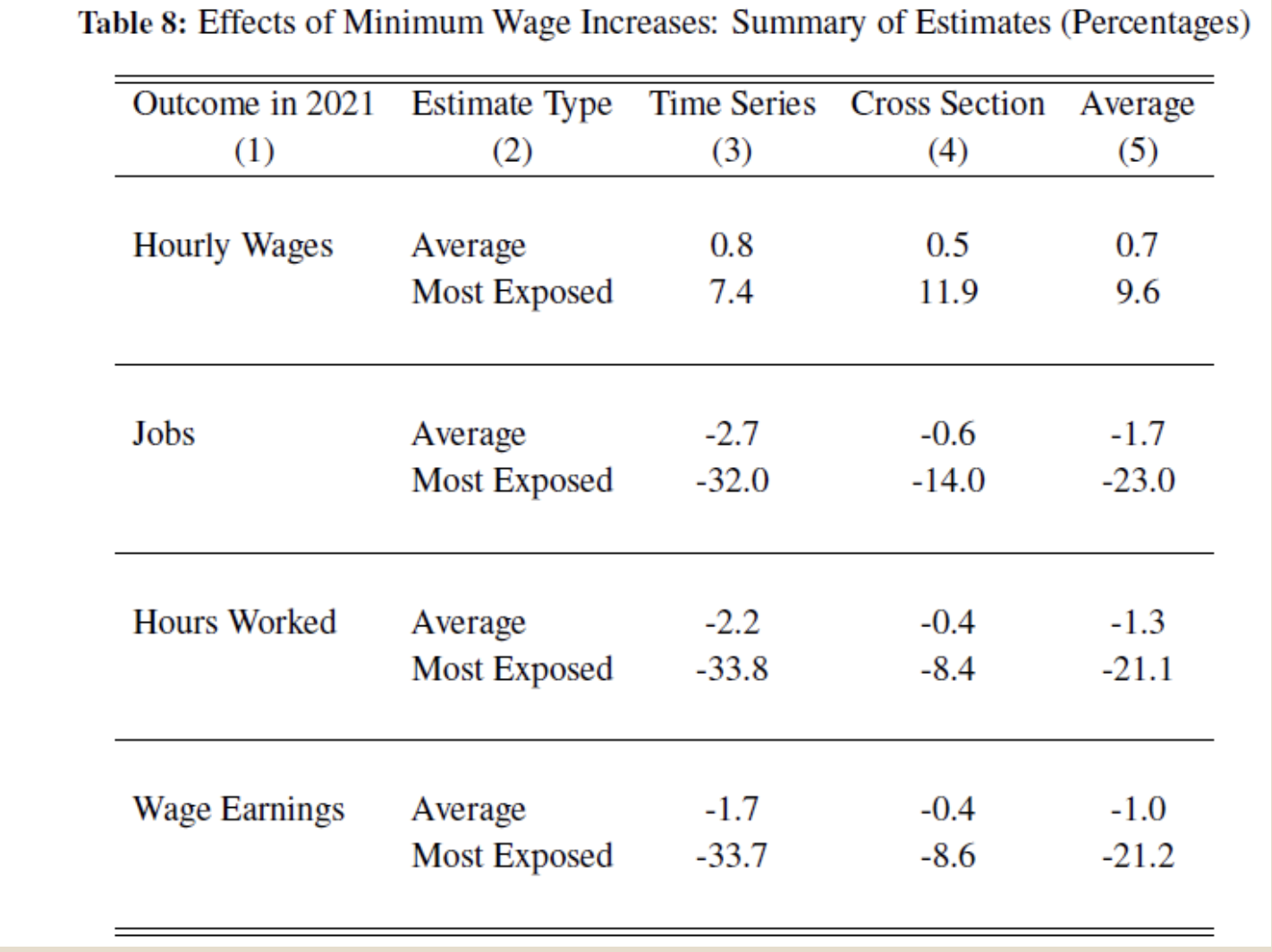

The first column shows four categories of outcomes. The second column shows an average effect for all jobs, and also just for the industries whose share of lower-wage workers made them “most exposed” to an increase. The third column, “Time Series,” is average results from the two synthetic control method. The fourth column, “Cross Section,” is results from the comparisons across establishments and across workers with different exposures to a higher minimum wage. The final column averages results from the two previous columns.

The overall results are similar to those from a number of other studies. As one might expect, the effects are much smaller for the average of all jobs than for the most exposed industries. A minimum wage tends to raise wages (for those who still have jobs), but leads to a decline in job and a decline in hours worked. For the average job, the higher wages and lower hours worked pretty much balance each other out, so total earnings don’t change much. For the jobs most-exposed to a minimum wage increase, the drop in hours exceeds the rise in wages, so total wage earnings decline.

My bottom line here is not to cheerlead for or against higher minimum wages. I’m trying to make the point that serious studies using a variety of methods show genuine tradeoffs–especially for industries that tend to pay lower wages and for those working in such industries. A serious discussion of minimum wages won’t ignore such tradeoffs or try to sweep them aside with assertions of how things “should” be. Specifically, a substantially higher minimum wage in a city will discourage some industries more than others, and in this way affect the mix of goods and services available nearby to residents of the city, and will have heavier effects on the hours and jobs of workers in those industries, too.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest