Comments

- No comments found

For any society, productivity growth is the difference between living in a zero-sum polity, where gains for some can only come as a result of costs for others, and a positive-sum policy, where social arguments can be about the distribution of gains rather than the imposition of losses. I sometimes say that no matter what your economic issues are, it’s a lot easier to achieve them in a positive-sum world.

Martin Neil Baily has spent a career studying productivity growth. He offers an overview of how this area of research has evolved along with his own insights in “Lessons from a Career in Productivity Research: Some Answers, A Glimpse of the Future, and Much Left to Learn” (International Productivity Monitor, Spring 2023, pp. 120-149).

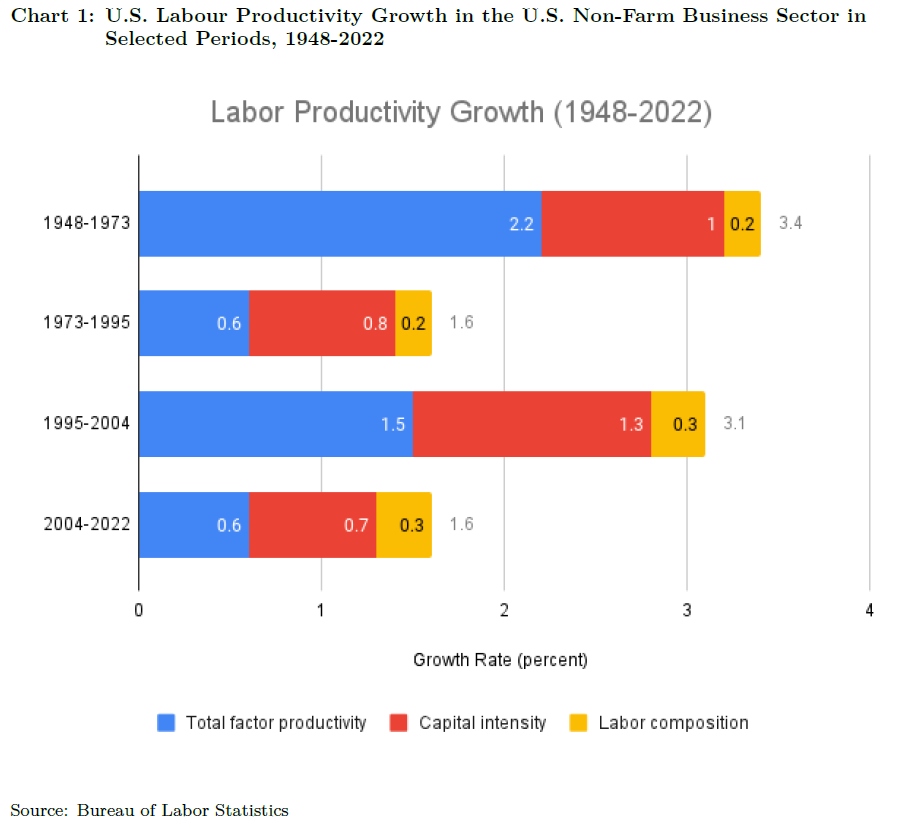

Here are a few figures to illustrate some of the background. The US economy since World War II has gone through four periods of labor productivity growth, as shown in the figure. A key insight here is that additional capital per worker can be measured in economic statistics, and “labor composition” can be approximated by factors like years of school completed and labor force experience. But the remaining productivity growth (the blue bars) is calculated as a “residual”–that is, the leftover part of GDP growth that cannot be attributed to changes in capital and labor is called “productivity.” In an old phrase (I think it traces back to Moses Abramowitz), productivity for economists is “a measure of our ignorance.”

The higher productivity growth from 1995-2004 is typically attributed to an acceleration of productivity in the manufacturing of computers and electronics products, which includes semiconductors. But the question of why productivity growth dropped so sharply in the early 1970s, and why it has not rebounded more in the last couple of decades, remain open questions. Is it becoming harder to achieve technological gains? Are economic statistics not properly capturing those gains? These are active areas of study.

In thinking about productivity, it’s important to remember that it’s an annual change. Thus, the gap between the good and the bad periods of US productivity is about 1.0-1.5% per year, each year. Over a decade, the higher productivity would mean that GDP was 10-15% higher.

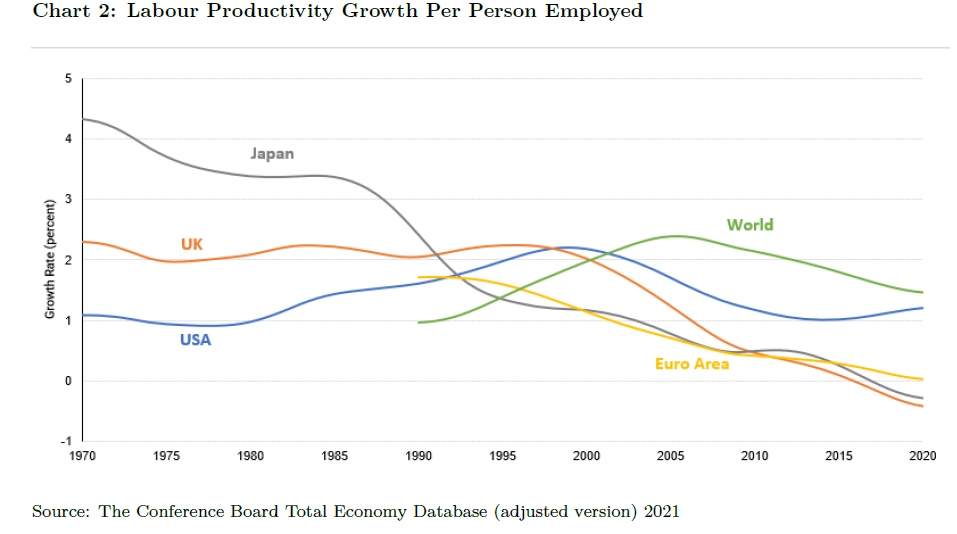

The lower US productivity growth is actually a phenomenon across high-income countries. The productivity levels in this figure are “smoothed” to emphasize long-run patterns rather than chunks of time. But what’s striking is that for the EU, Japan, and the UK, productivity gains have essentially fallen to zero percent.

A substantial portion of Baily’s research has involved looking at productivity levels by industry and by company. Here are some main takeaways:

First, the studies found that there were large differences in the levels of productivity across countries in the same industry. … Second, a high level of competitive intensity forces firms to achieve the level of productivity of the best performers in their industry, or close to it. And if companies compete against the most productive companies world-wide, they move closer to that best-practice productivity level. Third, certain types of regulation, as well as trade and investment restrictions, can prevent an industry in a country from achieving best-practice productivity. Fourth, operating at large scale often provided a productivity advantage. And fifth, promoting high productivity is not a simple thing. The drivers of productivity or the barriers to productivity varied by industry and country. …

[T]he productivity studies found in most cases that the way factories or offices or retail facilities were operated were much more important to productivity than differences in the capital stock. Organizational or managerial capital was very important. And there were even examples where high levels of investment

had contributed almost nothing to productivity. The study of Korea, for example, found that government development policies had, in some industries, encouraged overinvestment where machinery was underutilized. Another example came from Germany where union restrictions on shiftwork meant that companies had to invest in extra capital to produce a given level of output and capital utilization was low compared to the United States.

A further lesson that emerges from this research is that diffusion of productive methods across firms seems to have slowed. As Baily writes: “The distribution of productivity levels within industries has become wider. That is to say, the gap between the low-productivity establishments and the high-productivity establishments has increased.” To put it another way, the overall slower productivity growth is perhaps not the result of the technological leaders failing to make gains, but rather the result of other firms not keeping up in the kinds of organizational and managerial changes that spur productivity.

Looking ahead, a primary question is when or whether higher productivity will return. One theory is that productivity gains have gotten harder over time. But when one looks at scientific breakthroughs–say, in genetics, materials science, computing power, and others–it’s not obvious that the resulting economic growth should be rising more slowly.

Of course, the current hot topic is artificial intelligence. Baily points out that the new AI tools are both developing very quickly and being adopted very quickly. Baily points to the emerging evidence on how these tools might affect productivity. I’ve discussed much of this same evidence in “The New AI Techologies: How Large a Productivity Gain?” (May 22, 2023), “Biggest Economic Applications of Generative AI: McKinsey” (June 29, 2023), and “Technology and Job Categories in Decline” (July 14, 2022).

Baily mentions a couple of points worth emphasizing here. First, a common pattern in recent decades has been that improvements in information technology often tended to replace previously middle-class jobs and add to inequality. Back in the 1990s, there used to be a lot of middle managers whose job was essentially to collect information (say, about all the people doing sales in a certain territory) and then pass it along to upper management. But with information technology, those middle management jobs could largely be automated on to a computer “dashboard.” However, some of the evidence for the new AI tools is that they provide bigger benefits to the less-skilled, and thus they could potentially be a force for greater equality. As Baily writes: “Many people find it hard to write coherent emails or to do mathematics. As a result, they are forced to take manual jobs with low wages. The new technologies can potentially help them to be more productive. There are signs from some of the case study evidence cited above that generative AI can help those with weaker skills become substantially more productive.”

The other issue is that Baily, like most economists, has some tendency to separate questions of productivity and distribution. The idea is to encourage and to accept the greater gains from rising productivity, and then to use a share of those gains helping those in need. Baily writes: “Rather than focus on the dangers of new technologies it would be better to figure out how to take advantage of them, mitigate the adverse impacts and use these breakthroughs to improve the economic future broadly.”

We all have a feeling now and then that it would be nice–and less threatening–if the pace of change would just slow down. But the idea that government regulators have a good sense of how to shape the future of AI seems implausible to me. Imagine a similar set of government regulators in, say, 1985, trying to decide on how to regulate the shape of the internet. Special interests seeking to block change, or direct it to their own gain, are likely to be more powerful than shadowy and unknown future benefits across society as a whole. In a global economy, those who hold back will be overtaken by those who move ahead.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest