Comments

- No comments found

It’s fairly well-known that US labor force participation–that is, the share of U.S. adults who are classified either employed or unemployed–has been dropping.

But it’s not always recognized how the U.S differs from other high-income economies in this trend, or how.

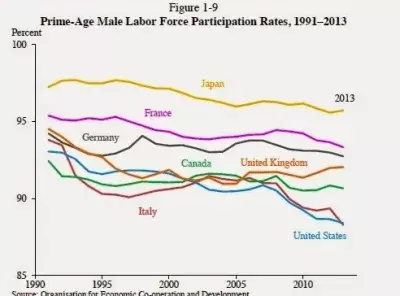

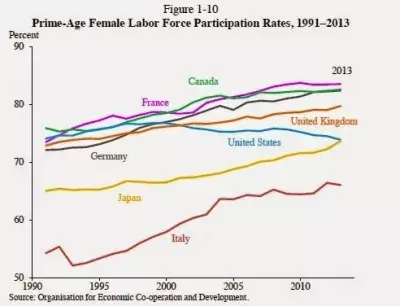

The Economic Report of the President, released by the White House Council of Economic Advisers, offers some striking evidence on these points. The top figures show labor force participation rates for ”prime-age males,” who fall into the 25-54 age category. The nice thing about looking at this group is that countries may differ considerably in their patterns of the extent to which students attend school into their early 20s, or the extent to which people retire in their late 50s and early 60s. Looking at the ”prime-age” group leaves these ages out of the picture.

For men, the U.S. was middle-of-the-pack in labor force participation rates of prime-age males in 1990, and now vies with Italy for the lowest level. For women, the U.S. was near the top-of-the-pack prime-age labor force participation in 1990, but since then has been surpassed by France, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom, and is now about even with Japan–which has not been historically known as a country with high labor force participation for women.

The Council of Economic Advisers sums up the cross-country patterns in this way:

Since the financial crisis, U.S. prime-age male participation has declined by about 2.5 percentage points, while the United Kingdom has seen a small uptick and most large European economies were generally stable. Of 24 OECD countries that reported prime-age male participation data between 1990 and 2013, the United States fell from 16th to 22nd. The story is somewhat similar among prime-age females. … In 1990, the United States ranked 7th out of 24 current OECD countries reporting prime-age female labor force participation, about 8 percentage points higher than the average of that sample. But since the late 1990s, women’s labor force participation plateaued and even started to drift down in the United States while continuing to rise in other high-income countries, as shown in Figure 1-10. As a result, in 2013 the United States ranked 19th out of those same 24 countries, falling 6 percentage points behind the United Kingdom and 3 percentage points below the sample average.

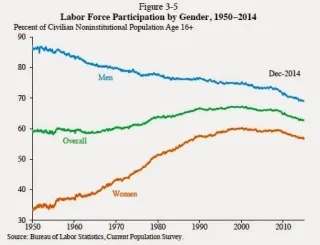

These patterns of decline in US male and female labor force participation go back in time. The share of the male population above the age of 16 in the labor force has been falling for decades. The share of the female population above the age of 16 in the labor force rose steadily in the second half of the 20th century, but levelled out around 2000 and has been falling since.

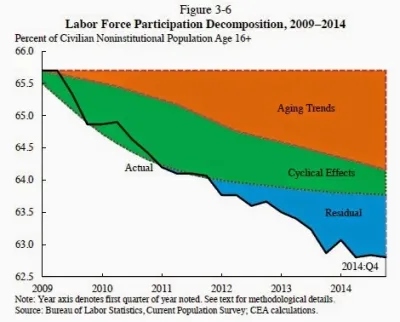

When combining the cross-country data, the time series data, and the depth of the Great Recession, the report argues that the decline in labor force participation rates in recent years is pretty well explained. The CEA writes:

Between 2007 and 2012 the decline in participation is fully (and at some points more than fully) explained by the aging of the population and standard business-cycle effects. Beginning in 2012, however, the labor force participation rate decline began to exceed what was predicted from aging and cyclical factors. Since late 2013, the labor force participation rate has stabilized and the portion of the decline that was unexplained shrank, albeit slowly, between the second and fourth quarters of 2014 …

What explains the ”residual” factor in the figure below? Part of it is probably due to a gradually lower rate of labor force participation within US age groups (like the evidence on prime-age workers given above), while another part is surely due to the fact that the Great Recession was so severe that it ”led to a greater-than-normal cyclical relationship between unemployment and participation.”

Whatever the reasons, as the U.S. economy looks ahead to the next few decades, figuring out ways so that the decline in labor force participation can be stabilized and reverse is an important goal of public policy.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest