Comments

- No comments found

The World Development Report is one of the flagship annual reports for the World Bank: for 2023, the theme is “Migrants, Refugees, and Societies.”

The report defines a simple summary, but here are a few key points.

The World Bank defines “migrants” as those who are living outside the country of their nationality: thus, someone who emigrated to the United States would be counted as a migrant unless or until they became a citizen, and then wouldn’t count as a migrant any longer. With this definition:

As defined in this Report, there are globally about 184 million migrants (about 2.3 percent of the world’s population)—37 million of them refugees:

About 40 percent (64 million economic migrants and 10 million refugees) live in high-income countries that belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These are high- and low-skilled workers and their families, people with an intent to settle, temporary migrants, students, as well as undocumented migrants and people seeking international protection. This number includes 11 million European Union (EU) citizens living in other EU countries with extensive residency rights.

About 17 percent (31 million economic migrants) live in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

Nearly all of them are temporary workers with renewable work visas. They represent, on average, about half of the population across GCC countries.

About 43 percent (52 million economic migrants and 27 million refugees) live in low- and middle-income countries. They moved primarily for jobs or family reunification or to seek international protection.

The share of migrants in the global population has remained relatively stable since 1960. However, this apparent stability is misleading because demographic growth has been uneven across the world. Global migration increased more than three times faster than population growth in high-income countries and only half as fast as population growth in low-income countries.

That final sentence, of course, is part of the reason for much of the political turmoil over immigration in high-income countries.

At the most basic level, the economics of migration starts from the evidence that the migrants themselves benefit. They may benefit in some cases because they are moving to places of greater opportunity, or in other cases because they are escaping repression or persecution, but their gains are real and should appear in the social calculus. But migration also affects non-migrants in both the sending and receiving countries in a variety of potentially positive and negative ways, and so political controversy is inevitable.

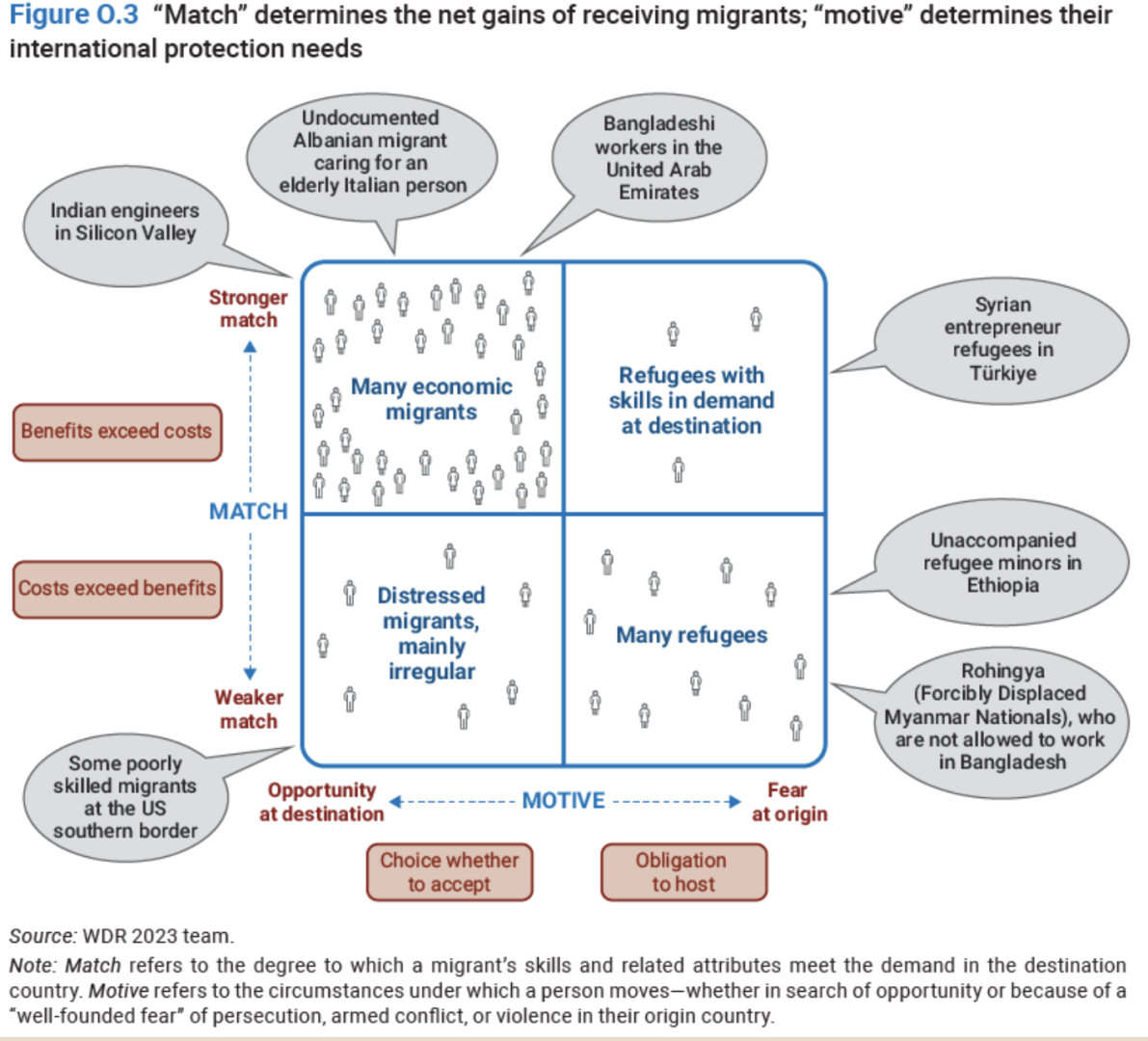

The World Bank suggests that one framework for thinking about these issues from the standpoint of the receiving country is the “match-motive matrix.” When immigrants are a good match for pre-existing needs in the receiving country and, the receiving country as a whole will gain. When the match is poor, as when the migrants do not have skills needed in the receiving country and perhaps are refugees seeking only to escape persecution, then the costs for the receiving country may exceed the benefits.

From the standpoint of those remaining in the origin country, migrants to other locations can also bring benefits by sending remittances and providing knowledge transfers. In some cases (nurses from the Philippines are a commonly cited example), the fact that migrants will go to work in other countries provides a strong reason to build up domestic institutions that can provide skills to those remaining in the country of origin as well.

The report works its way through the policy choices that need to be made in sending countries, receiving countries, and multilateral agreements to increase the benefits of migration and, in the case of refugees, to find ways to share the costs. I also expect that the ongoing spasm of immigration across the southern US border will lead to policy changes. Here, I’ll just close with a broader theme: rules about migration are in many ways similar to rules that affect society as a whole. For example, how can we support children from families with low incomes and limited educational backgrounds to realize their potential as adults contributing to society? How do we support people of diverse backgrounds in living side by side? As the report notes:

This debate plays out in a context in which societies and cultures are neither homogeneous nor static. There is no “pre-migration” harmony to return to. In every society, tensions, competition, and cooperation have always existed across a variety of groups that are partly overlapping and constantly changing. Some of these tensions reflect socioeconomic divides: they are not about migration but about poverty and economic opportunity—and large numbers of migrants happen to be poor. Because many of those who moved or their descendants have been naturalized, some of the cultural issues attributed to migration are, in fact, about the inclusion of national minorities. Migration is also just one of many forces transforming societies in an age of rapid change, alongside modernization, secularization, technological progress, shifts in gender roles and family structures, and the emergence of new norms and values, among other trends.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest