Comments

- No comments found

About one-third of US households rent, rather than own. The renters are disproportionately lower-income, less-educated, and younger.

The public policy concern, of course, is not really about, say, a group of college students or recent graduates sharing a rental, but instead about low-income adults and parents with families for whom rental housing may comprise a very large share of their incomes. Lauren Bauer, Eloise Burtis, Wendy Edelberg, Sofoklis Goulas, Noadia Steinmetz-Silber, and Sarah Wang from the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution present some basic facts in “Ten economic facts about rental housing” (March 2024).

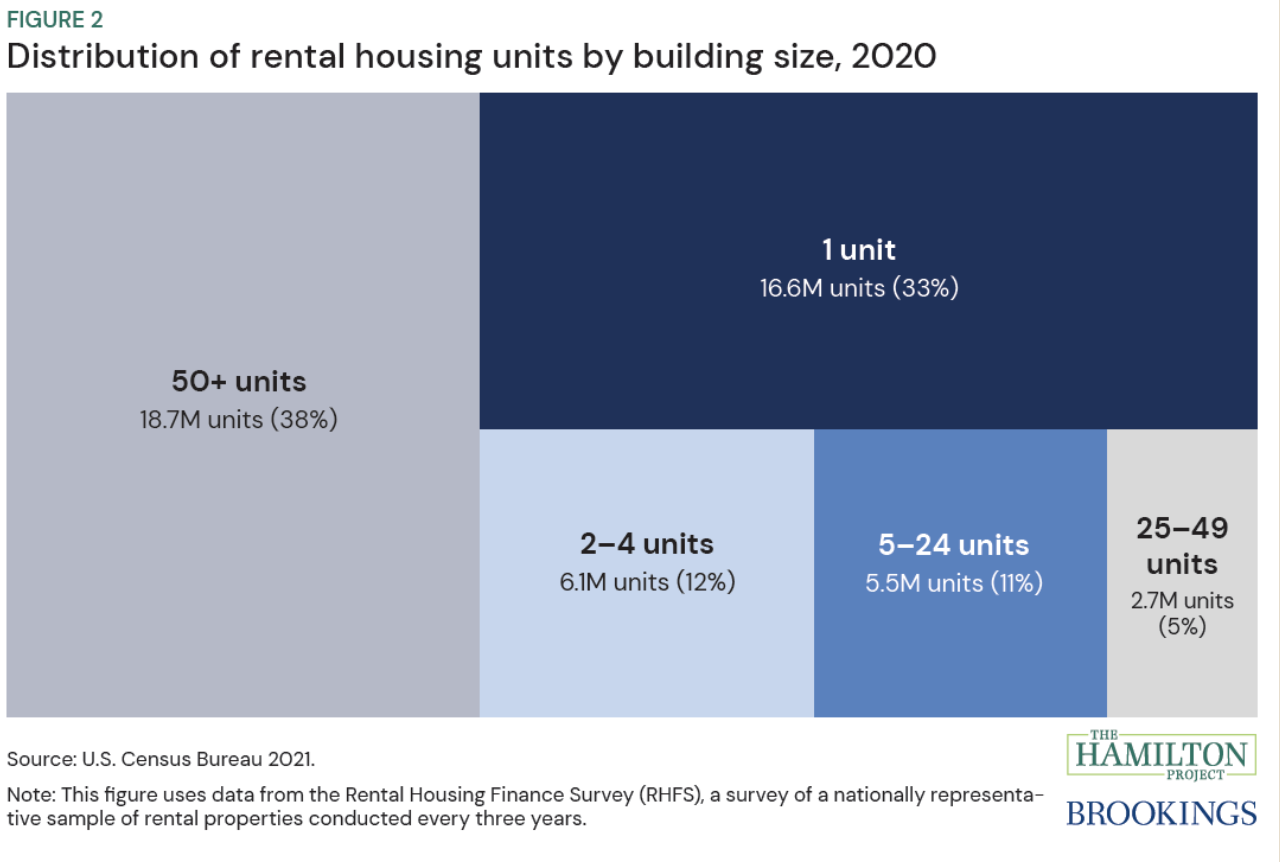

When you think about rental housing, do you think about apartment buildings with dozens of units, or about smaller scale rentals? It can come as a surprise to recognize that, in the US housing market, landlords offering just one rental unit in a building nearly as many total rental units as rental buildings that include 50 or more units. When thinking about rental housing policy, it’s important to remember that it’s not just about big investors with a large number of rentals, but also about the incentive that applies to the very large number of smaller units.

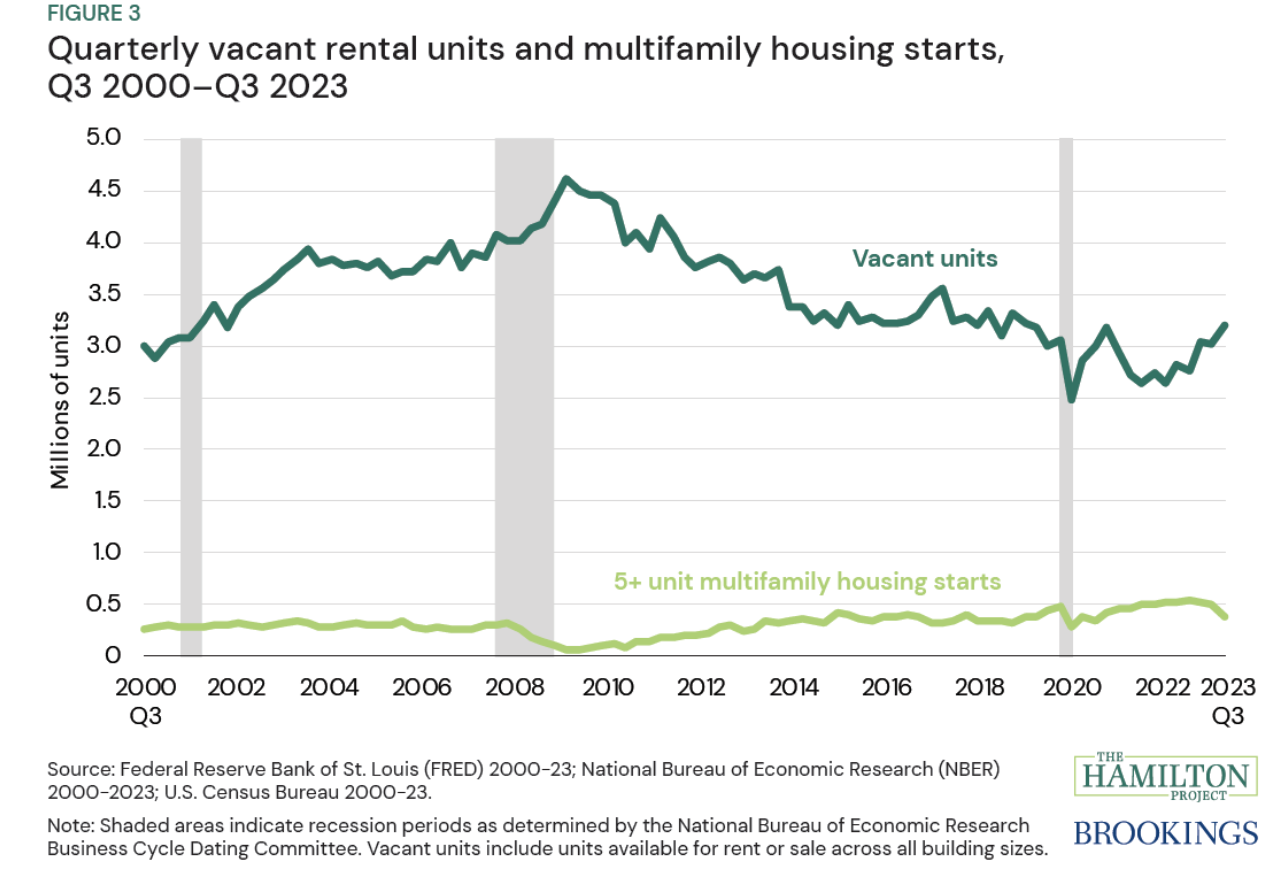

By the standards of the last two decades, the number of vacant rental units is low, although new construction of rental units did seem to be turning up a bit through much of 2022 and 2023.

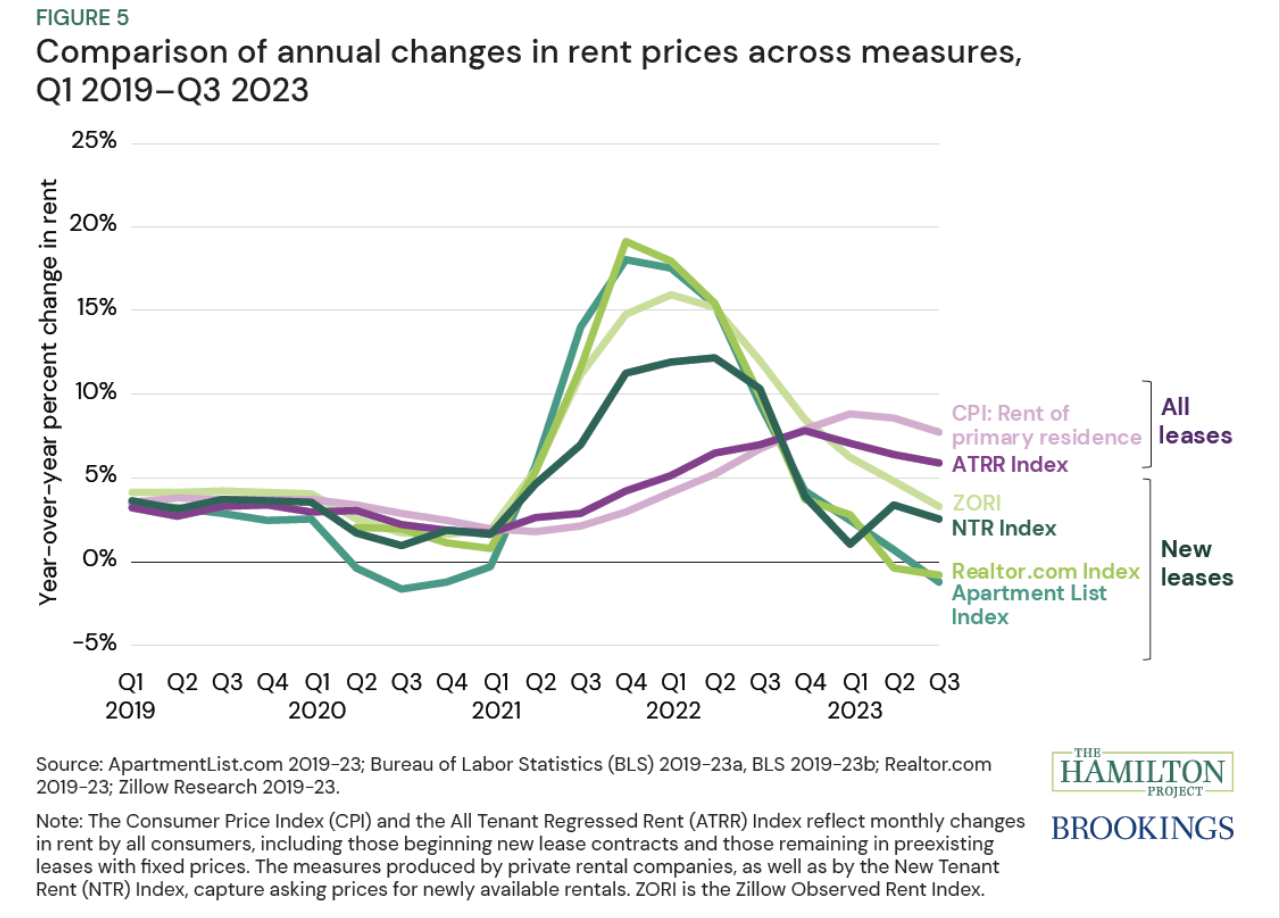

The price of new rentals spiked during the pandemic, as shown by the three shades of green lines that show different surveys of new rental prices. The price of existing rentals didn’t rise during the pandemic, in part because the federal government passed rules making evictions from rental apartments essentially illegal for a time. But as the figure shows, the higher prices of new rentals started feeding through into the price of existing rentals in 2022 and 2023.

For households in the middle fifth of the income distribution, rent is typically about 28% of income. For those in the bottom fifth of the income distribution–who have less income to begin with–rent in recent years has been 34-36% of total income. Federal housing support is not especially high. The Hamilton Project authors explain:

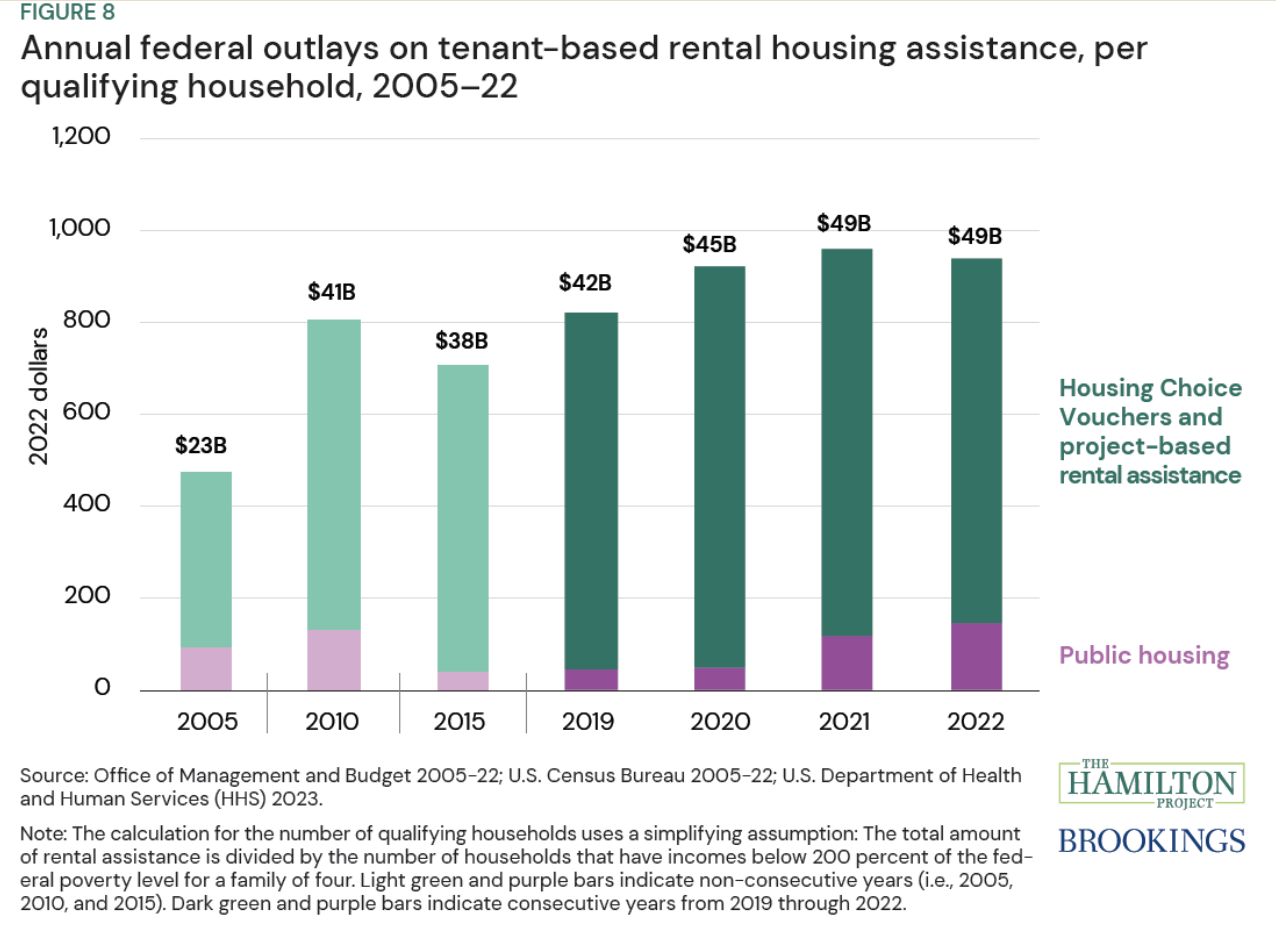

Figure 8 shows annual federal outlays for housing assistance per potentially eligible household (defined as a household with income below 200 percent of the poverty threshold for a family of four) between 2005 and 2022. Annual housing assistance per household is very low relative to average housing costs. In this period, annual federal housing assistance doubled from $475 (in 2022 dollars) per qualifying household per year ($23 billion in total) to $941 per qualifying household per year ($49 billion in total). Meanwhile, the median asking rent per month in the U.S. in November 2023 was $1,967 (Redfin 2023).

In many cities, the waiting lists for those who are eligible to receive housing vouchers can be lengthy–measured in years.

Like a lot of economists, I’m ambivalent about providing specific vouchers for housing, rather than providing those with low incomes with additional cash so that they can make life tradeoffs as they see best. But the US political system has preferred to earmark support for different areas–Medicaid for health care, food stamps for food, housing vouchers for rental housing–while keeping cash payments to the poor relatively low, and often linked to work.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest