Comments

- No comments found

The goal of electrifying everything is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources.

One of the big-picture strategies for reducing carbon emissions into the atmosphere goes under the shorthand “electrify everything.” The basic idea is that if sufficient electricity could be generated in carbon-free ways, it could replace fossil fuels in many uses–not just in generating electricity, but also as fuel for transportation, for home heating, for industrial uses, and so on. What would be required over the next few decades to make this happen? For a useful starting point on the basics, a group of authors at the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution have written a background paper “Ten Economic Facts about Electricity and the Clean Energy Transition” (April 27, 2023). Here are a few of their facts that caught my eye.

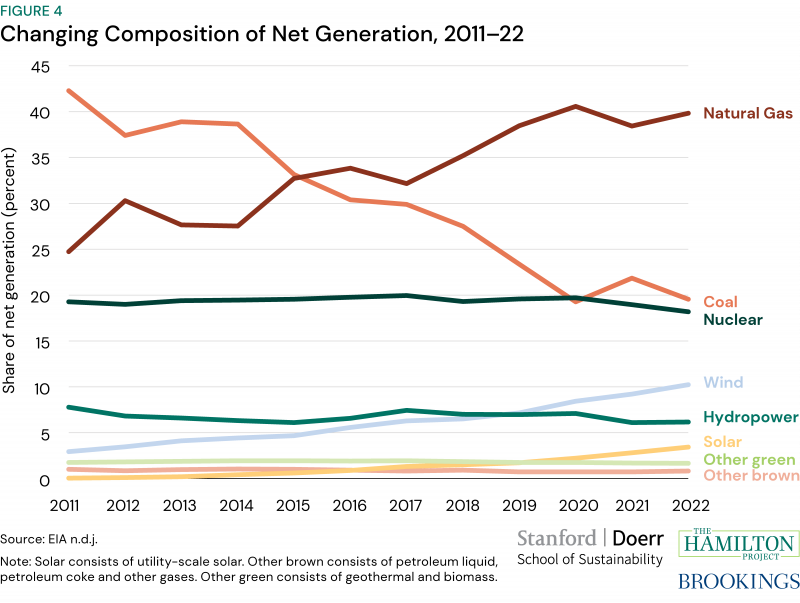

The composition of sources for electricity generation has changed substantially in the last decade.

The big shift, as the graph shows, is a decline in the share of electricity produced from coal and a rise in the share produced from natural gas. An optimist will note that electricity from natural gas emits only about half the carbon of a coal-fired plant; a pessimist will note that electricity from natural gas still produces about half the carbon of a coal-fired plant. Toward the bottom of the figure, you can also see the substantial rises in electricity generated from wind-power and from grid-scale solar.

Is the existing growth rate of wind and solar sufficient for these sources of energy to serve as the basis for an “electrify everything” scenario?

The answer is “no.” As the graph above shows, it will take decades at the current pace for solar and wind to provide sufficient electricity to dominate the electricity grid. But in the US economy only about 27% of greenhouse gas emissions come from electricity. A similar share of carbon emissions comes from transportation, and a similar share again from industry uses, with the rest of emissions coming from commercial/residential real estate and from agriculture. For the “electrify everything” agenda to work (even with whatever energy conservation efforts are possible), the US electricity grid will need to be dramatically larger than it currently is–and the needed expansion of wind and solar would need to be much larger, too. Of course, an upturn in nuclear power would reduce the need for expanding wind and solar, as well as providing baseline energy for nights when the wind isn’t blowing.

Solar has become the cheapest way to generate electricity–at least on sunny days in the right locations.

The authors of the report note:

Solar is, on a levelized cost (meaning apples-to-apples) basis, the cheapest source of new energy today and is likely to play a central role in the buildout of a zero-carbon grid. It is cost-effective to have more solar generation because the production costs are lower: although costs can vary substantially based on a variety of factors, the average cost to produce one megawatt-hour of utility-scale solar energy ranges between $28 and $41 compared to between $45 and $74 and between $65 and $152 for the equivalent amount of energy from natural gas and coal, respectively (Lazard 2021). As a result, new construction of solar far outpaces new natural gas plants and there is no new coal under construction in the United States (EIA n.d.e). The growth of solar will need precise planning to fully exploit the benefits of its lower cost while accommodating its intermittency.

The quotation points to several major issues with solar and wind power. One is that they are intermittent sources of energy, so backup power is needed for say, frigid windless winter nights in Minnesota, where I live. Another is that solar and wind power are somewhat location-specific: that is, you can build a natural gas-burning electricity plant pretty much anywhere, but the cost-effectiveness of solar and wind depends on whether they are located in sunny or windy locations.

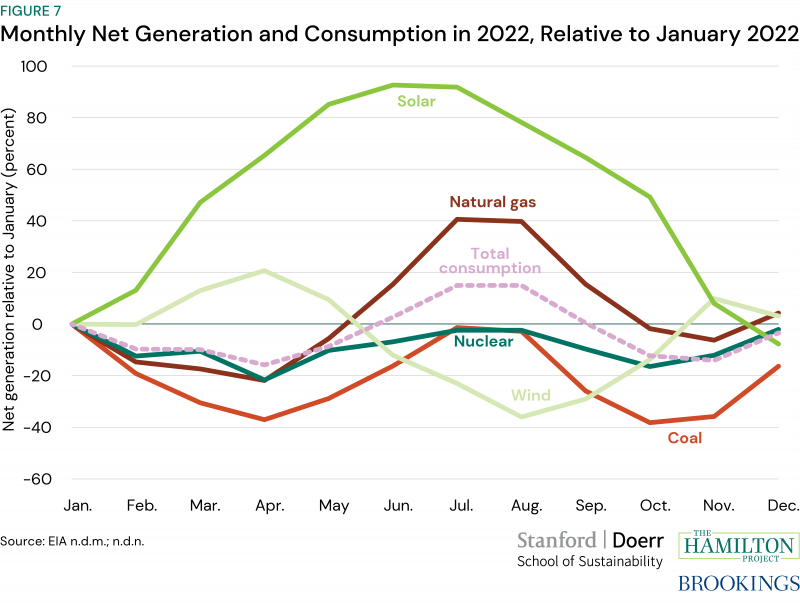

The problem of intermittent power from solar and wind isn’t just day-to-day–it’s also an annual fluctuation.

The dashed blue line in the figure shows month to month consumption of electricity in 2022, compared to January. Notice that demand for electricity drops off a little in January and February, then rises in the summer with the demand for air-conditioning, and then drops off again in the fall. This consumption pattern is more-or-less matched by fluctuations in solar power, which is at its lowest in the shorter, colder days of January, and much higher by mid-summer. (It’s important to be clear that the graph shows percentage changes compared to January, not quantities. Thus, the graph does not say that solar produces a high enough quantity to cover all consumption!) Wind power drops off in the summer. Different parts of the country are more likely to use either electricity from natural gas or from coal, which helps to explain the seasonal movements in these electricity sources.

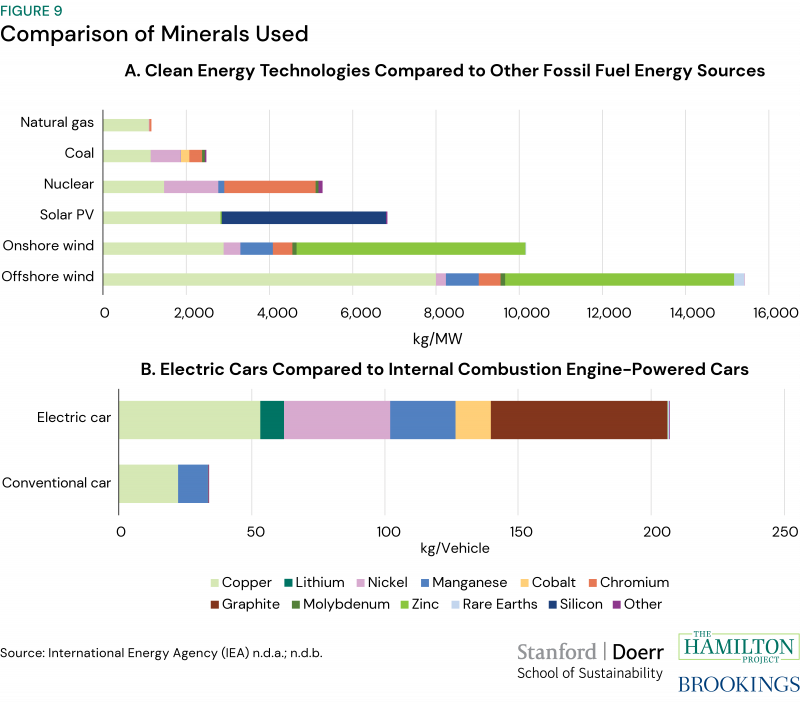

The “electrify everything” agenda requires a dramatic increase in mining and processing of minerals, for uses like solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries of electric vehicles.

The report notes: “A typical electric car uses more than five times more minerals than an internal combustion engine-powered car, which raises issues around where US companies source those minerals. Similarly, relative to energy produced by coal and natural gas, wind and solar energy are also mineral intensive, relying on significant quantities of zinc and silicon …”

The “electrify everything” doesn’t just require generating the electricity, but also requires transmitting it across potentially long distances from the solar panels or the windmills to the users.

To make the “electrify everything” agenda work, you need to imagine a dramatically larger quantity of electricity than is currently produced being moved on average longer distances–from south to north, from windy to not windy. This step involves not just a financial cost and a need for minerals and materials to expand the grid, but also plans and political power to build new right-of-way for these many new electricity lines all around the country. Sure, some of these can be expansions of transmission lines along existing right-of-way. But remember that the new solar and wind generation will be at the locations naturally best-suited to generate power, which in many cases is not going to be where existing electricity-generating capacity is located. So dramatic expansions of the right-of-way are going to be needed, too.

The “electrify everything” agenda isn’t impossible. But it’s daunting. And a number of those who favor the agenda in theory are not eager to support many of the actual specific steps needed to make it happen. It won’t be possible to dramatically expand generating capacity, mineral production, and transmission lines without some noticeable tradeoffs.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest