In April 1994, almost 30 years ago, Nelson Mandela was elected as the first black president of South Africa.

The hopes at the time went beyond developing a representative political process, and included the idea that policies of inclusive growth would raise the standard of living for those who had been excluded.

How is that economic promise working out? A research group at Harvard’s Growth Lab spent two years researching the issues, and has now published its discouraging findings in “Growth Through Inclusion in South Africa” (November 15, 2023). The authors are Ricardo Hausmann, Tim O’Brien, Andrés Fortunato, Alexia Lochmann, Kishan Shah, Lucila Venturi, Sheyla Enciso-Valdivia (LSE), Ekaterina Vashkinskaya (LSE), Ketan Ahuja, Bailey Klinger, Federico Sturzenegger, and Marcelo Tokman.

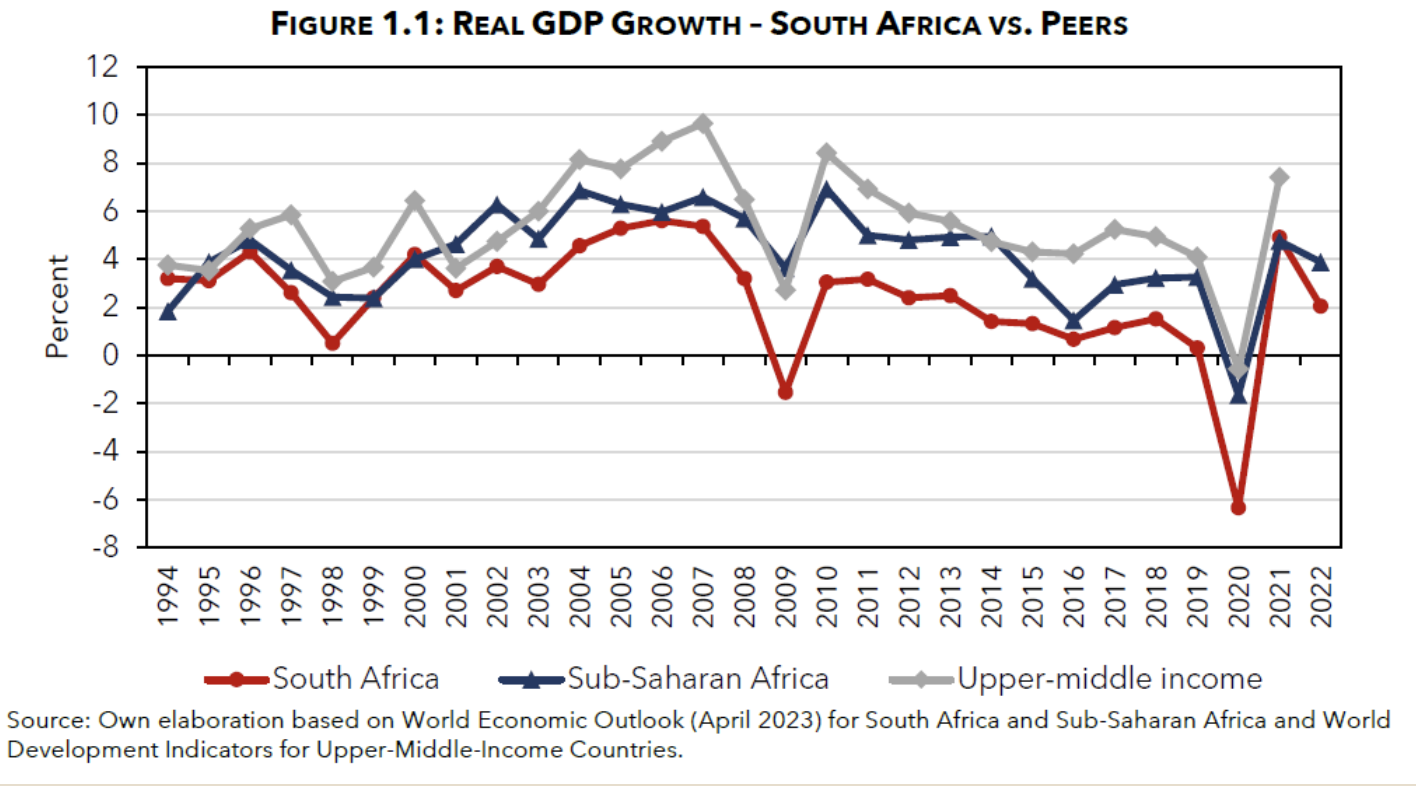

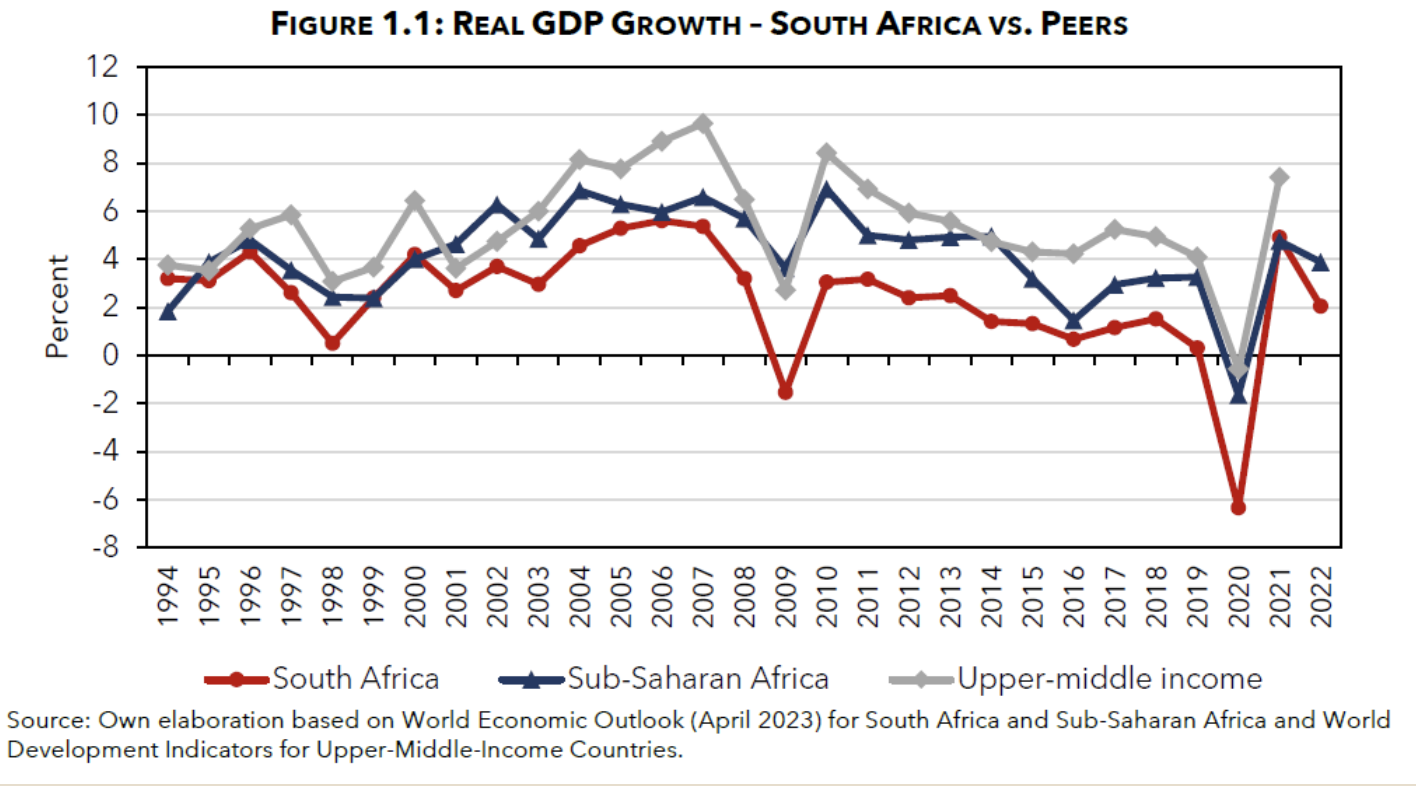

The basic story is that for the first decade or so after 1994, South Africa’s economy performed reasonably well; since then, not so much. This panel shows annual growth rates for South Africa (red line), compared with the rest of sub-Saharan Africa (blue line), and the upper-middle income countries of the world (gray line).

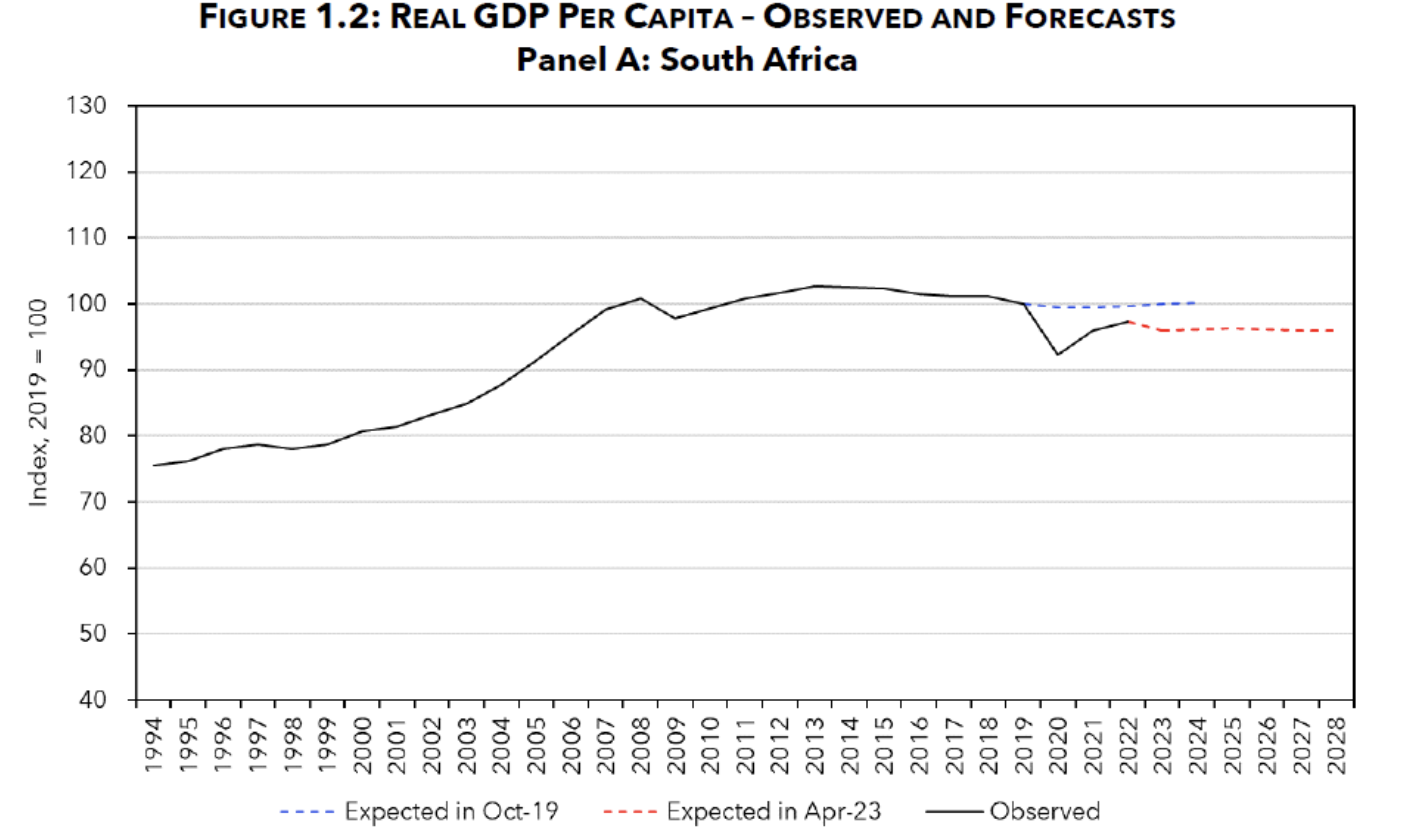

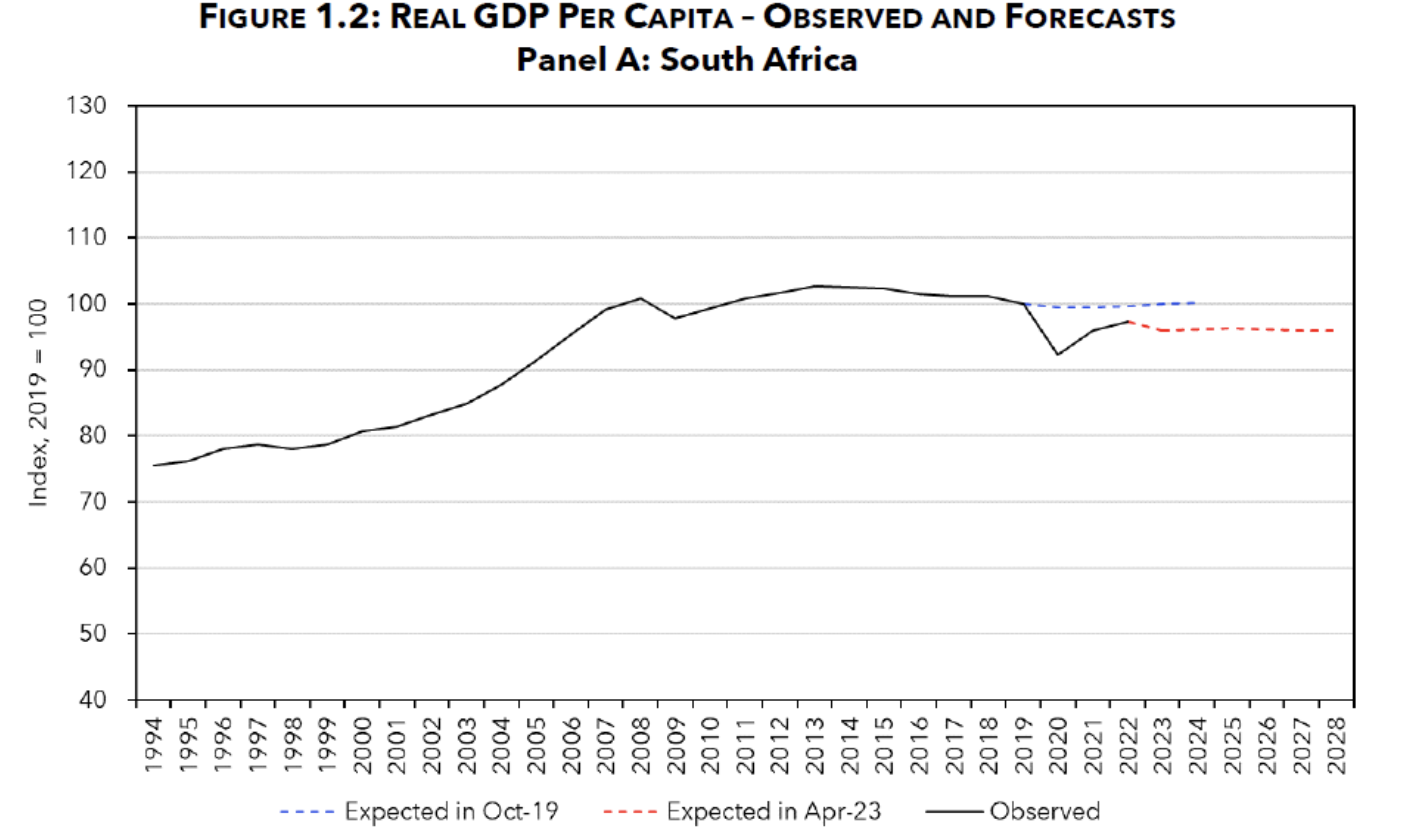

This graph shows South Africa’s real per capita GDP since 1994. You see the pattern of reasonably rapid growth for the first decade, and then no growth since then. (In other words, the growth shown in the figure above has only been keeping pace with population growth since 2004 or so.) The dashed lines on the far right show pre-pandemic and post-pandemic projections.

As the report says:

Income per capita has been falling for over a decade. Unemployment at over 33% is the world’s highest, and youth unemployment exceeds 60%. Poverty has risen to 55.5% based on the national poverty line, yet many more households depend on government transfers to sustain meager livelihoods. Most cities are failing to adequately connect people to productive opportunities and are failing to innovate, grow, and drive inclusion. Rural areas in former homelands, where almost 30% of South Africans live, exhibit dismally low employment rates and remain exceptionally poor.

The report suggest two main categories of economic failure that are plaguing South Africa’s economy:

This report aims to answer why South Africa is failing to grow and failing to move the needle on economic inclusion three decades after the end of apartheid. The evidence points to two causes: collapsing state capacity and the persistence of spatial exclusion.

State capacity has collapsed across many government functions that are essential for a functioning economy. Critical network industries, including electricity, transport infrastructure and services, security, and water and sanitation have experienced major deteriorations over the last 15 years. The economy has been forced to cope with increasing electricity rationing, leading to a declaration of national disaster in February 2023 after more than 15 years of load shedding. Rail and port capacity has declined, generating large losses in exports. The collapse in state capacity to deliver key inputs has, in effect, squandered the country’s comparative advantage in cheap, coal-fired electricity. Urban crime is very high, and theft and sabotage undermine the functioning of many national infrastructure systems. Communities across the country are increasingly vulnerable to all forms of disaster — both natural and manmade — due to weakened public services. National finances are under increasing strain as South Africa relies on fiscal transfers to bail out state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and to redistribute national income to households to alleviate poverty and hardship. Many municipalities now face severe fiscal challenges which undermine already weak public service delivery. South Africa is seeing signs of unsustainability in its repeated credit downgrades and large sovereign risk premia. All the while, as growth slows, exclusionary forces are becoming more entrenched.

Spatial exclusion has been entrenched by well-intentioned policies in urban areas and an absence of effective strategy to include rural former homelands. Under apartheid, townships were intentionally separated from central business districts and economic infrastructure, leading to fragmented and disconnected cities. Apartheid also relied on differential treatment to former homelands vis-à-vis the rest of the country, effectively separating those areas from the industrialized economy. Despite attempts to reverse this exclusion, policies since 1994 have unintentionally perpetuated many aspects of spatial exclusion. We find that urban planning regulations and zoning policies prevent dense, affordable housing in desirable locations and consequently limit both formal and informal employment. We also find strong evidence that formal jobs are limited because long commutes from low-density areas in and around cities make transportation costs and reservation wages high, while low residential densities prevent the development of a thriving informal economy. Meanwhile, rural former homelands continue to be economies separate and distinct from the rest of the country and face extremely low rates of employment. …

It is unfortunately clear that South Africa’s trajectory is not one of growth or inclusion, but rather stagnation and exclusion. South Africa’s economy is stagnating and, in fact, losing capabilities, export diversity, and competitiveness. While the racial composition of wealth at the top has changed, wealth concentration in South Africa has not and remains very high. Moreover, the broader structures of the economy have not allowed for the inclusion of the labor and talents of South Africans — black, white, and otherwise. There appear to be major spatial impediments to labor market inclusion in cities and large spatial patterns of exclusion in former homelands. As the performance of network industries and public capabilities have deteriorated and growth has slowed, exclusion has only worsened. Empowerment of a few has de facto come at the expense of the many.

The report goes into considerable detail on these issues. It also raises the possibility that South Africa could be well-positioned to benefit from a global shift to carbon-free and low-carbon electricity production: as a producer of key minerals needed for batteries and other uses, as a producer of domestic solar and wind power, and as a source of technological expertise in these areas. These shifts could also rebuild what used to be a comparative advantage for South Africa as a place with cheap (albeit coal-generated) electricity.

But overall, South Africa’s economy is on a disheartening path. The issues of improving the functioning of government and addressing the long-standing patterns of spatial exclusion is hard, and in the last couple of decades, South Africa’s government and political system hasn’t been up to the task. A virtue of this report is that it effectively lays out an agenda for what needs changing.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest