Comments

- No comments found

Economics textbooks teach that one role of central bank during a financial or economic crisis is to act as a short-term “lender of last resort”: that is, when the financial system is in danger of freezing up in a way that can lead to an expanding vicious circle of defaults–as those who can’t get roll-over loans are unable to repay others, who also can’t roll over their loans, and son on–the central bank makes short-term credit available.

When the panic passes, the central bank lender-of-last-resort loans get repaid: indeed, because the central bank was the only one willing and ready to make large-scale loans during the crisis, it can even end up making some money from the interest it charges on these loans. Often some firms will end up going broke in the aftermath of the crisis, but the purpose of a lender-of-last-resort policy is not to do a complete or widespread bailout of specific firms. Instead, the goal is to prevent the market as a whole from melting down.

In the last decade or so, the Federal Reserve has transformed how it conducts monetary policy, and recently, part of the new policy seems to involve acting as a borrower of last resort. Kyler Kirk and Russell Wong of the Richmond Fed explain the situation in “The Borrower of Last Resort: What Explains the Rise of ON RRP Facility Usage?” (Economic Brief, December 2021, No. 21-43).

The starting point here is that when the Federal Reserve conducts monetary policy, it seeks to control a specific interest rate called the “federal funds” rate, which can be thought of as a rate at which depository institutions like banks are willing to make very short-term and low-risk overnight loans to each other, often for the purpose of settling up accounts at the end of a business day.

The primary method that the Fed uses for affecting this interest rate is to alter the interest rate that it pays to banks on the reserves that the banks hold at the Fed. But a secondary backup method is to use the ON RRP, which stands for the Fed’s Overnight Reverse Repo facility. For an overview of the ON RRP and how it works, here is a good starting point. But for present purposes, the key is that the ON RRP allows big financial players, like money market mutual funds as well as banks or pension funds, to lend money to the Fed on a very short-term and thus low-risk overnight basis. What’s peculiar is that the amount of Fed borrowing through the ON RRP exploded in size during 2021. Kirk and Wong explain:

The idea is that the ON RRP facility gives participants in the short-term funding market the risk-free overnight option of lending to the Fed at the guaranteed ON RRP rate. Thus, other lending rates — like the fed funds rate — will be above the ON RRP rate. … In the original design, ON RRP was a backstop, as market participants should lend to banks or others (via federal funds, repo, wholesale deposits, commercial papers, etc.) before lending to the Fed. This was the case during the early stage of the pandemic: The daily usage of ON RRP averaged $8.7 billion from March 2020 to March 2021. However, ON RRP usage steadily increased after March 2021 and reached an unprecedented $1.6 trillion in September 2021. This hints at an excess supply of nonbank savings that is not intermediated by banks or absorbed by Treasuries, which has ultimately flowed into the ON RRP facility. The Fed becoming the borrower-of-last-resort has prompted concerns about how the U.S. banking system is functioning during the pandemic.

In case that blob of text was a bit much to read, let me hit the high points one more time. The ON RRP was intended as a backup for short-term overnight lending. But from March 2021 to September 2021, this backup expanded in size from $8.7 billion to $1.6 trillion. Any shift from a few billion to more than a trillion is a huge deal. Apparently, there is $1.6 trillion or so in funds that large-scale market participants want to lend short-term, overnight, and the Fed is the only party in the market willing to be the borrower–the borrower of last resort, if you will.

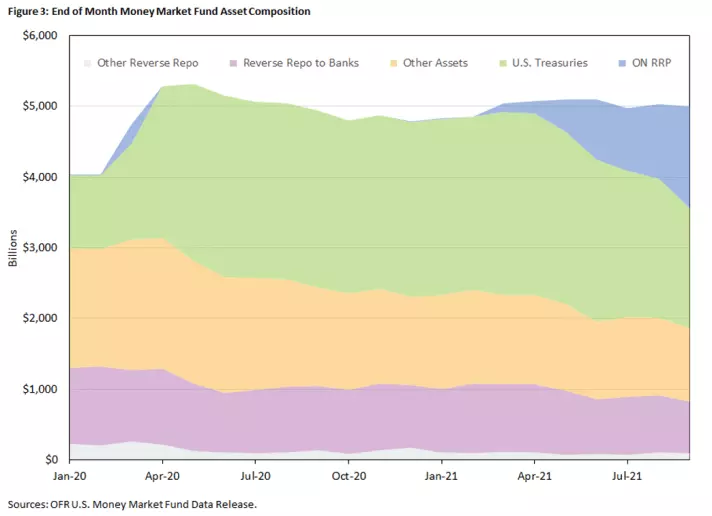

Here are a couple of factors going on behind the scenes. Start by considering money market mutual funds. These funds are required to hold only highly liquid short-term assets, so that they can readily finance any withdrawals. When the pandemic hit the economy in March 2020, more investors wanted the safety and flexibility of holding assets in a money market mutual fund, so as you can see from the figure below, the holdings of such funds went up by well over $1 trillion. These additional assets were largely held in US Treasuries, as shown by the upward jump in the green area of the figure. But starting in April 2021 and since then, the holdings of money market mutual funds have shifted. Instead of holding US Treasuries, money market funds are now holding well over $1 trillion in the Federal Reserve’s Overnight Reverse Repo (ON RRP) facility.

What’s behind this dramatic rise and fall in US Treasuries? The story behind the scenes is that when the pandemic recession hit, the US Treasury felt that it needed to have more liquid assets on hand, in case of a banking or financial panic. But then starting in spring 2021, the Treasury began to reduce its holdings of these assets. As Kirk and Wong explain:

In particular, the Treasury has been draining reserve balances in the Treasury General Account (TGA), which is the reserve account maintained by the Treasury to make and receive payments in the banking system. The Treasury has been reducing this account with the Fed by issuing fewer T-bills, effectively releasing these reserves into the banking system. Pre-COVID, the TGA maintained a moderate balance that averaged $290 billion in 2019 and varied with financial conditions and government spending. However, due to uncertainty around the COVID-19 pandemic and the magnitude of the fiscal response, the Treasury increased the TGA balance from approximately $380 billion in mid-March 2020 to an unprecedented $1.6 trillion by June 2020. This rapid increase was primarily facilitated by an expansion in T-bills outstanding from $2.56 trillion in March 2020 to over $5 trillion in June 2020. The Treasury maintained the elevated TGA balance and T-bill supply through February 2021 before normalizing via a reduction in T-bill supply. TGA normalization decreased the TGA from over $1.6 trillion in February 2021 to less than $100 billion by October 2021, primarily through T-bill supply falling from $5 trillion to $3.7 trillion. This effectively reduced the supply of risk-free short-term assets by $1.3 trillion …

So roughly speaking, the US Treasury dramatically increased its holdings of short-term Treasury bills at the start of the pandemic. As market investors moved into money market funds, the money market fund held more of this short-term debt. But then the Treasury decided to hold less short-term T-bill debt, and while market investors still wanted a very safe place to stash their liquid reserves overnight–and they turned to the Federal Reserve ON RRP account. So far, this arrangement seems to be working OK. But as far as I know, no one anticipated that the Fed would become both a lender of last resort in financial crises and also a borrower of last resort as the economy recovered.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest