Comments

- No comments found

The question of whether a burst of inflation turn into permanent inflation should depend, at least in part, on expectations about inflation.

If workers and firms expect higher inflation, then the workers are more likely to press for higher wages to compensate–and firms are more likely to be amenable to such increases. An inflationary cycle can emerge where expectations of higher inflation lead to more price and wage increases, and those price and wage increases lead to higher inflation.

However, the evidence of the last couple of decades is that people’s expectations of inflation aren’t very accurate. Instead, people’s expectations often react to past rises or falls in inflation after they have happened. John O’Trakoun of the Richmond Fed gives a short overview of the evidence in “Your Attention Please …” (Macro Minute, February 5, 2022). He writes:

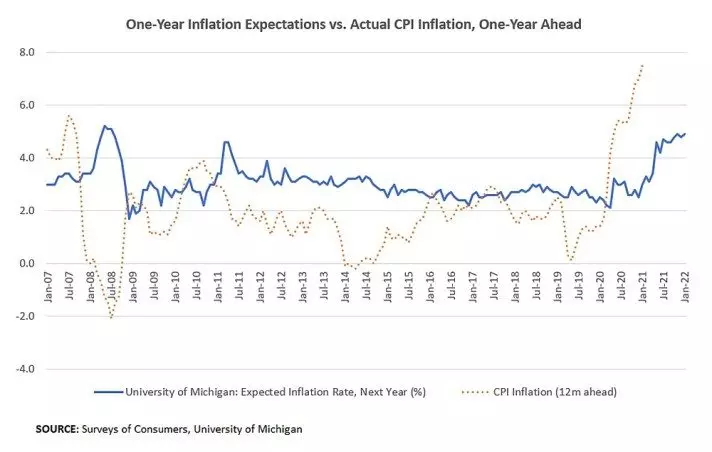

Historically, households have not been very good at predicting inflation. Figure 1 below plots the expected one-year inflation rate from the survey against realized Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation a year later. Since 2007, the correlation between the two measures has been -0.35, which casts doubt on whether this survey tells us much about future inflation at all. But as we explore in this post, consumers’ expectations may now have some additional weight.

Here’s an accompanying figure. The blue line shows people’s expectations of inflation a year into the future. The red dashed line shows what inflation actually happened, but shifted back by 12 months. Thus, the right hand side of the figure shows that about a year ago, people were forecasting inflation of about 3.5% a year in the future; the red line shows that the actual rate of inflation turned out to be more like 7.5%,

There are couple of patterns worth noting in the graph. First, you can see several situations where inflation expectations change in response to earlier movements in inflation–and can end up being completely wrong. For example, the left-hand side of the graph shows how inflation expectations were rising in 2008 at about the same time that actual inflation turned out to be plummeting during the Great Recession. When people tell you what inflation they are “expecting,” it often looks as if they are actually telling you what inflation they recently experienced. Second, you can see that for most of the decade from 2010 to 2020, inflation expectation just didn’t change much, even when actual inflation fell and then rose. A plausible interpretation here is that many people haven’t paid much attention to inflation for the last decade.

Thus, one possibility is that inflation expectations don’t much match inflation when people aren’t much paying attention, and when inflation is fluctuating in a fairly narrow range. But if inflation stays higher for a significant time, in a way that is salient to many people, then the chance that current inflation expectations feeding into future inflation become higher.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest