Comments

- No comments found

“Globotics” is the name that Richard Baldwin gave to the combination of globalization and robotics in service jobs.

In his essay “Globotics and macroeconomics: Globalisation and automation of the service sector” (presented at the ECB Forum on Central Banking 2022, June 27-29, where videos of presentations and comments are included), he argues that you can’t understand the likely future of globalization without it.

Baldwin argued that the global economy is in the throes of a third “unbundling” of globalization, which is a phrase he uses to describe the driving force behind a shift in what is traded across global borders. In his telling, the first “unbundling” “happened when steam power and Pax Britannica radically lowered the cost of moving goods,” and the unfolding process of reduced physical transportation costs over the decades drove the rise of globalization from the 19th century up to the 1960s or 1970s (with interruptions for world wars, the Great Depression, and other events).

The second “unbundling” kicked in around 1990. It wasn’t about transportation costs, but rather about information and communication technology (ICT) and how it affected firms in big high-income countries like the G7 group (the United States, Canada, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan). In particular, it wasn’t about how economies of some countries were able to produce goods at different prices, which is the standard intro-level theory of trade, but rather how a combination of higher-technology manufacturing firms in high-income countries could coordinate their production chain with lower-wage labor in other countries. Baldwin writes:

Globalisation changed dramatically around 1990 when it entered its offshoring-expansion phase, or what I have called the “second unbundling” to contrast it with the first unbundling (Baldwin 2006). This was triggered by the ICT revolution which relaxed the second separation cost – communication and coordination costs. ICT made it feasible for G7 firms to fragment highly complex industrial processes into production stages, and then spatially unbundle some of them to low-wage nations. Think of this as the offshoring-expansion phase of globalisation where G7 manufacturing firms seized low-hanging opportunities for combining their advanced manufacturing knowhow with foreign low-wage labour in factories set up abroad. As the offshored process had to continue to operate as if it were still bundled, we can think of this as factories crossing borders, not just goods. Trade boomed again.

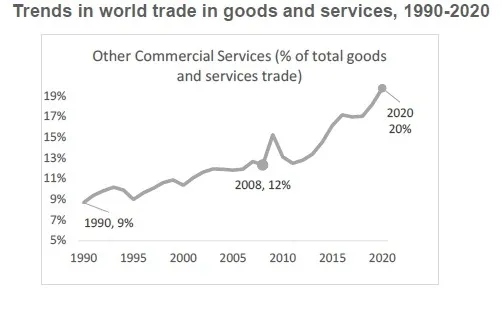

This third “unbundling,” now underway, is about how the newest versions of interconnected information and communications technology, which one might just call the digital economy, are connecting services industries. Indeed, although the rise in international trade in goods has more-or-less levelled off since about 2008, international trade in services has continued to rise and is becoming an ever-larger share of international trade.

What exactly are these “other commercial services”?

The OCS category consists of a few big items and many small items. Some are easily recognisable. Among the bigger categories are Financial Services (9%), and payments for intellectual property rights. The category Telecommunications, Computer, and Information Services accounts for 11% of the total; much of this is made up of computer services related to software, but a large share is tossed into the category ‘Other computer services other than cloud computing’ (this is typical of the lack of precision in trade statistics). The largest sub-category (23%) is ‘Other Business Services’. This includes a broad array of services. Some – like Architectural, Financial, Engineering, R&D, Advertising and Marketing, and Professional and Management Consulting services – are easily associated with sectors and jobs. Others, like Operating Lease Services, and ‘Other Business Services, not elsewhere included’ are difficult to map into jobs and sectors in the domestic economy.

In my own mind, it’s perhaps useful to think of the third “unbundling” in terms of working from home. If your job is one that can be entirely done by someone working from home, by a telecommuter, then it can be done by someone outside the country. As one of many examples, the K-12 and higher education systems just spent a year delivering their services on-line. Baldwin writes:

Note that the arbitrage here is direct wage competition among service sector workers, and wage differences are probably the largest unexploited arbitrage left in today’s world. Taking Colombia as an example of a middle-income emerging market, a recent study matched the US’s occupation classifications with those of Colombia to compare wage rates (Baldwin, Cardenaz, and Fernandez 2021). Focusing only on the occupations that Dingel and Neiman (2020) have classified as teleworking in the US, the study found that the wages in the US were on average 1500% higher in the US than in Colombia. Plainly low wages are not the only source of competitiveness in services but with wage gaps being that large, it is likely that the digitech-driven globalisation of the service sector will have an impact on prices in advanced economies.

Some of the arbitrage is done via online freelancing platforms like Upwork, Freelancer, and Zhubajie (these are like eBay but for services). Wage comparisons based on worker-level data scraped from such online freelancing platforms confirm the presence of enormous wage gaps, although the size varies greatly according to the data selection criteria. Data from a number of the largest freelance platforms reported in ILO (2021) indicate that average hourly earnings paid in a typical week for those engaged in online work is US$4.9, with the majority of workers (66%) earning less than the average. While $4.90 an hour seems like a low wage in Europe, it corresponds to a full-time equivalent salary of about $10,000 per year – a salary which is considered comfortably middle-class in most countries.

Baldwin argues that the low-hanging fruit in this area is “intermediate services.” For example, it might be hard for a variety of regulatory reasons for a US firm to hire accountants directly from a company based in India or Brazil or Indonesia. But it’s pretty easy for US-based accounting firms to hire those accountants from other places, and to coordinate their work when delivering accounting services to US-based firms. Moreover, for a lot of emerging market economies, providing services can be pretty straightforward.

[E]xport capacity in emerging markets is not as great a limiting factor in services as it is in goods since every nation has a workforce that is already producing intermediate-service tasks. All emerging market economies have bookkeepers, forensic accountants, CV screeners, administrative assistants, online client help staff, graphic designers, copyeditors, personal assistants, travel agents, software engineers, lawyers who can check contracts, financial analysts who can write reports, etc. There is no need to develop whole new sectors, build factories, or develop farms or mines.

The term “slobalization” is used to describe the level of globalization slowing down. When it come to trade in goods, slobilization applies. But Baldwin’s analysis implies that the world economy may already be seeing the roots of a substantial rise in globalization that will happen via the services sector.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest