Comments

- No comments found

Here are three long-term shifts in the US budget picture, based on the most recent The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034 from the Congressional Budget Office (February 2024).

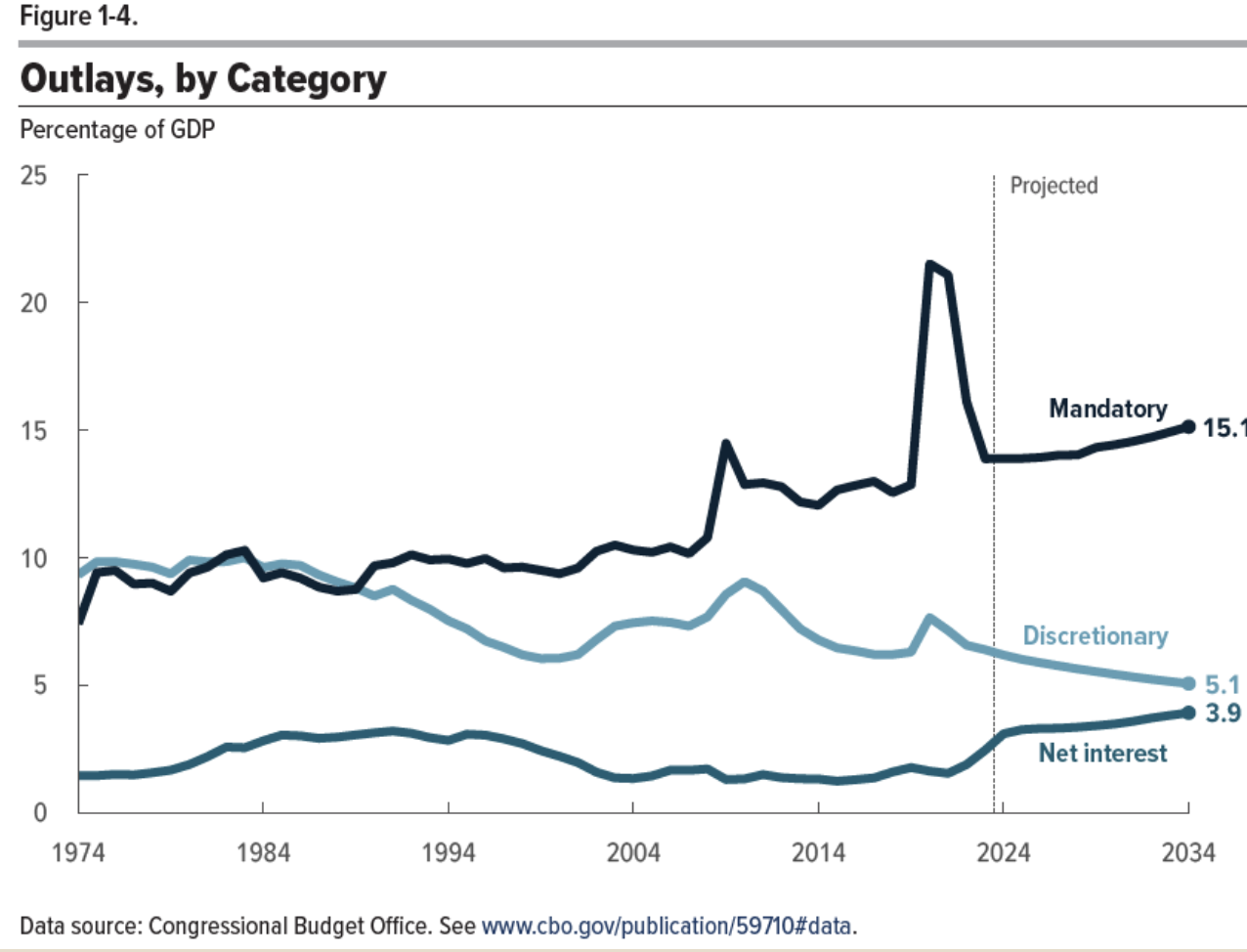

First, the major categories of US government spending have been shifting. Consider this graph showing federal spending divided into mandatory, discretionary, and net interest. The vertical axis measures spending as a share of GDP. As you can see, over the last half-century, the category of “mandatory” is way up, the category of “discretionary” is way down, and the category of “net interest,” while small, is at its highest level since the start of the CBO data in 1940.

What are these categories? “Mandatory” spending arises when the level of spending was predetermined by earlier legislation. A little more than one-third of spending in this category is related to health care: Medicare, Medicaid, and subsidies to make health insurance more affordable. A little less than one-third is Social Security. Other large categories are income support programs like the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit, food stamps, and others. Other items in this category include retirement programs for government workers and support for military veterans.

In contrast, CBO notes: “Discretionary spending includes most defense spending; spending for many nondefense activities, such as elementary and secondary education, housing assistance, international affairs, and the administration of justice; and outlays for certain transportation programs.”

As I have argued before, the big shift here is that the role of the federal government has been shifting toward making payments to individuals, and has become much and less about carrying out and managing projects.

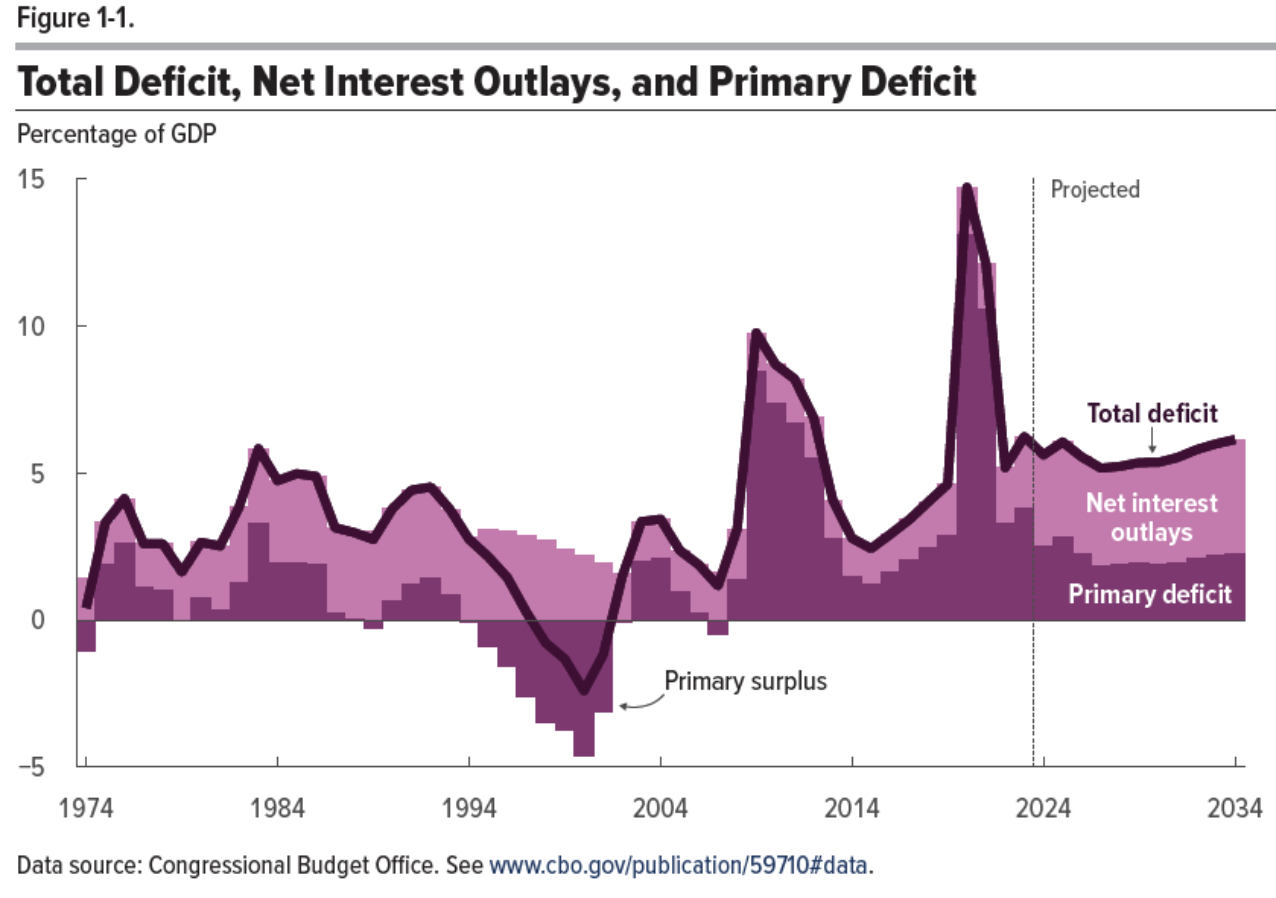

A second long-term change involves a shift between “primary” and overall budget deficits. The “primary” budget deficit is just the overall deficit, with interest payments subtracted out. As the figure from CBO shows, the projected “primary” deficits for the US government don’t look especially high by historical standards. But notice two shifts. First, in the last 50 years the primary deficit would rise and fall, and occasionally dip into becoming a primary budget surplus. Looking ahead in the next decade, it’s all primary deficits. Second, the higher interest payments mean that the gap between the primary and overall deficits has widened. The danger here is what I’ve called the “interest payments treadmill,” where the annual deficits stay large because of the high interest payments on past borrowing, which raises total debt in a way that guarantees even larger interest payments in the future.

For a while back around 2010, there was a lament among Democratic-leaning politicians and economists that they didn’t “go big” when raising spending in response to the Great Recession. When the pandemic recession hit, some of them were determined to “go big” this time. Personally, I think the government fiscal boost at the time of the Great Recession was about right, but the fiscal boost in response to the pandemic recession was too much. But whatever our judgements about the past, we now face the bills in the form of high interest payments.

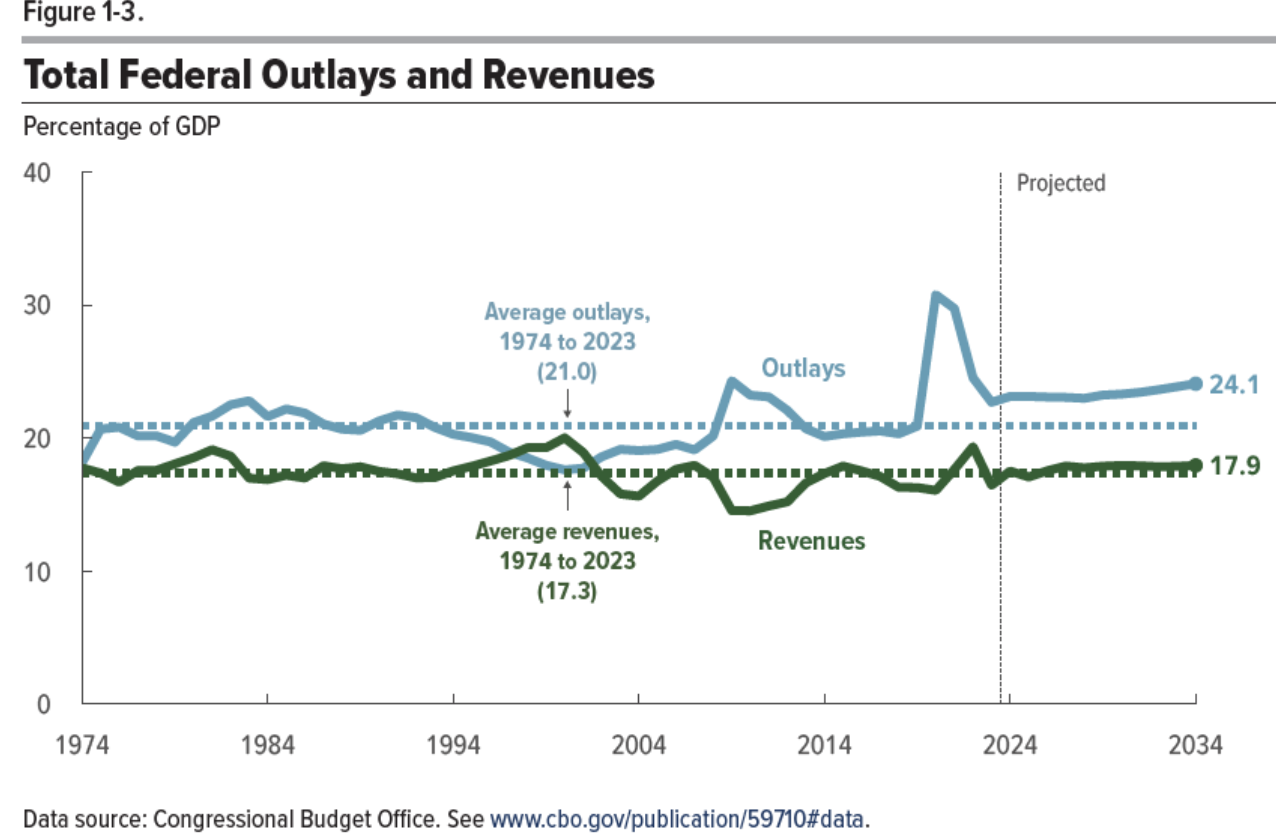

A third substantial change is the projection that federal tax revenues as a share of GDP are going to remain fairly close to their historical levels during the last half-century, while federal spending is moving to a higher level.

The main reasons for the shift in spending have already been mentioned: the rise in spending on the elderly as the Baby Boomer generation retires, a steady rise in health care costs, and the higher interest bills from previous government borrowing. There are fundamental choices to be made here. One option is for federal spending overall to rise in response to the growing share of the elderly in the US population. If we don’t want federal spending as a share of GDP to rise, then either we need to cut back on benefits to the elderly, or cut back on other federal spending, or raise taxes. Given that cutting back on interest payments is not a good idea, the “other spending” that can be cut has already been a shrinking share of the US budget for a few decades. Raising taxes isn’t any fun, nor is an ever-growing federal debt.

When it comes to the federal budget, we are headed in the next decade or so for a situation where either we either make choices at times of our own choosing, or we have choices forced upon us quite likely at times not of our own choosing.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest