Comments

- No comments found

Certain aspects of China’s evolving population structure have been widely discussed.

China’s fertility rates plummeted in the 1970s and have remained low since then, especially in the aftermath of the government’s “one-child policy.” There has been a saying in China about “six adults, one child,” illustrated by the idea of a child playing in a park with two parents and four grandparents watching–the result of two generations of one-child policies. As a result, China’s population structure has been shifting toward a greater share of elderly and a lesser share of children. In between, China’s own national statistics bureau has reported that the working-age population between ages 15-64 peaked in 2014 and has been declining since then. Earlier this year, China’s government has now acknowledged that deaths exceed births in 2022, and thus that China’s total population had declined.

Nicholas Eberstadt and Ashton Verdery dig into how these changes affect Chinese family and kinship networks in “China’s Revolution in Family Structure: A Huge Demographic Blind Spot with Surprises Ahead” (American Enterprise Institute, February 2023).

It’s a story of how demographic changes can echo for decades. In the 1950s and 1960s, the fertility rate in China was 4-5 children per woman. To put it another way, children born during this time had on average 3-4 siblings. If one person with 3-4 siblings marries another person with 3-4 siblings, and that couple has children, then the child will have 6-8 aunts and uncles, and a substantial number of cousins, as well. And this quick sketch doesn’t count the great-aunts and great-uncles from the generation of the grandparents–along with their descendants.

Eberstadt and Verdery emphasize that even when China’s fertility rate dropped dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s, it remains true that the parents of the children being born at that time were often from larger extended families. Thus it was possible for a few decades from the 1970s through the 1990s for a single child to have a substantial number of aunts, uncles, and cousins. But after multiple generations of low fertility, the average number of aunts, uncles, and cousins will diminish substantially.

China, like most other countries, does not keep official data on numbers of aunts, uncles, and cousins. Thus, Eberstadt and Verdery are forced to estimate these numbers in a way that is consistent with the information that is available about fertility, family size, mortality rates at different ages, and life expectancy. Here are some of their findings:

As recently as 1950, we estimate, only about 7 percent of Chinese men and women in their 50s had any living parents; the corresponding figure today (i.e., 2020) would exceed 60 percent (Table A1). Conversely, a decidedly larger fraction of Chinese men and women in their 70s and 80s have two or more live children today than around the time of the 1949 “liberation” (Table A2); they are also more likely to have a living spouse nowadays than in that much less developed era (Table A6).

By our estimates, men and women in their 40s are three times more likely to have two or more living siblings today than they were in 1950 (Table A3). In 1950, by our reckoning, only one in four Chinese in their 30s had 10 or more living cousins; today that share would be an amazing 90 percent or higher. And practically none of today’s 30-somethings lack cousins altogether, as opposed to about 5 percent of their counterparts in 1950 (Table A4).

Despite 35 years of coerced anti-natalism through Beijing’s notorious One-Child Policy (1980–2015), today’s teens in China are more likely to have 10 or more living cousins and vastly more likely to have 10 or more living uncles and aunts than their predecessors in 1950 were (Table A4). In fact, 10 or more cousins and 10 or more uncles and aunts looks to be the most common family type for teens in contemporary China (Table A5).

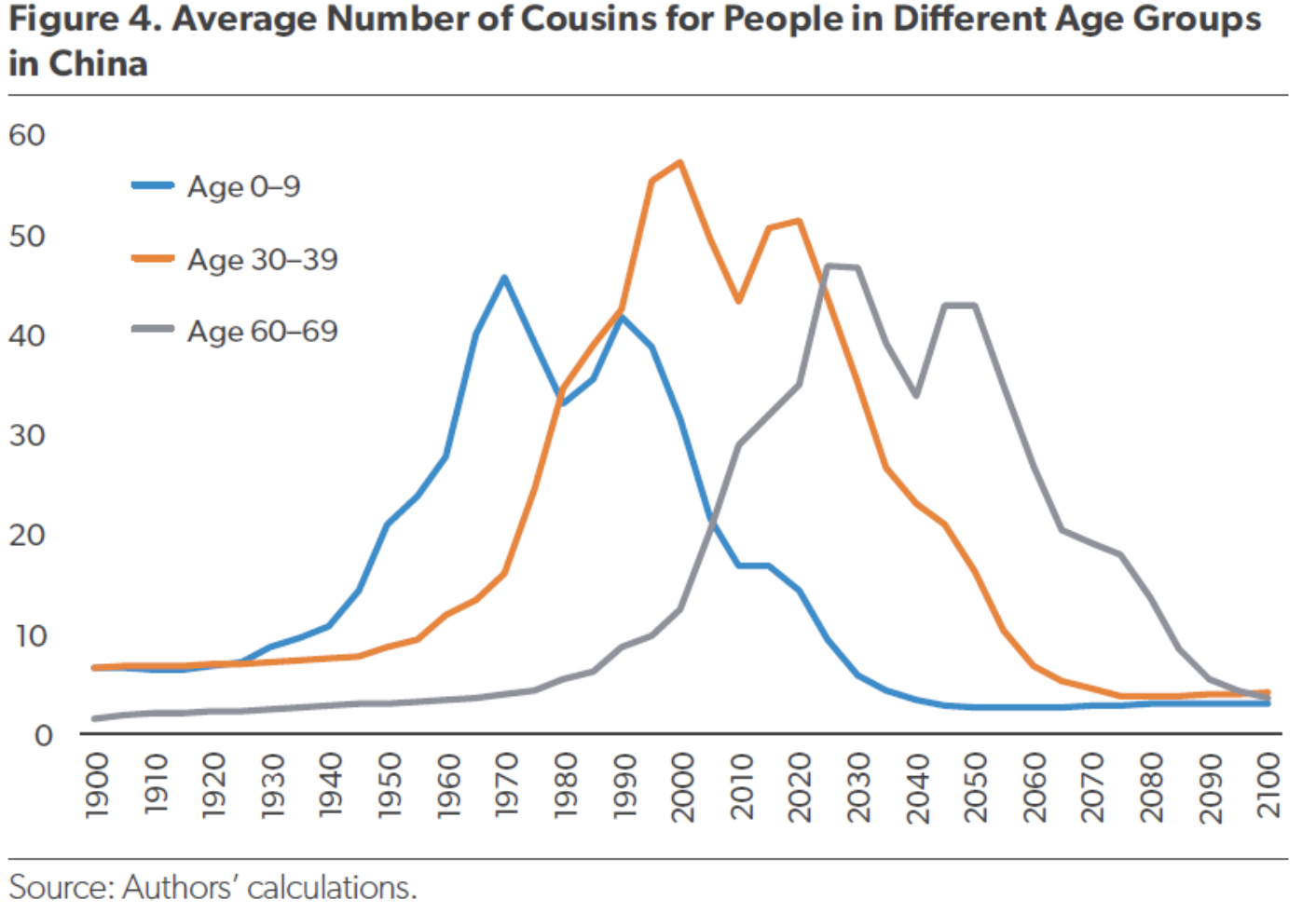

Here are their estimates of the number of cousins for people in different age groups. For the 0-9 age bracket at any given time, you can see that the number of cousins rises sharply in the early 20th century, with declining infant mortality and longer life expectancies, but then tops out and starts declining after fertility rates start falling in the 1970s. For those in the 30-39 age bracket at any given time, this pattern essentially happens 30 years later–although additional rises in life expectancy make the peak a little higher. For those in the 60-69 age bracket at any point in time, the rise and fall is again roughly 30 year later.

Again, the exact numbers here come from a population modeling exercise, and thus have a margin of error around them. But again, these numbers are based on the known estimates for population, fertility, and infant mortality, and so should capture any big-picture swings. Here are some main themes:

1) China’s extended networks of blood relatives may have been larger around the turn of the 21st century than at any previous time. In the words of Eberstadt and Verdery:

Our estimates obviously cannot speak to the (possibly changing) quality of familial relations in China, but in terms of sheer quantity, it seems safe to say that Chinese networks of blood kin have never been nearly as thick as they were at the start of the 21st century. … This proliferation of living relatives is a confluence of three driving forces: (1) the tremendous general improvement in life expectancy starting seven decades ago, (2) the generationally delayed impact of steep fertility declines on counts of extended kin, and (3) the as-yet-modest inroads of the “flight from marriage” (to borrow a phrase from Gavin W. Jones) witnessed already in the rest of East Asia, as well as affluent Europe and North America.

2) Extended family networks are a form of social capital: for example, during China’s period of dramatic economic growth, with all of its reallocations across industrial sectors and from rural to urban areas, deep kinship networks have been a way of spreading information about opportunities. Eberstadt and Verdery:

China has evidently enjoyed a massive “demographic deepening” of the extended family over the past generation or so—a deepening with many likely benefits, not least an augmentation of social capital. …

Social capital begets economic capital. China’s “kin explosion,” for instance, may have had highly propitious implications for guanxi, the quintessentially Chinese kin-based networks of personal connections that have always been integral to getting business done in China. With a sudden new wealth of close and especially extended relatives on whom potentially to rely, the outlook in China for both entrepreneurship and informal safety nets may have brightened considerably—and rapidly—in post-Mao China, as numbers of working-age siblings, cousins, uncles, aunts, and other relatives surged for ordinary people. It is intriguing that China’s breathtaking economic boom should have taken place at the very time that the country’s extended family networks were becoming so much more robust. No one has yet examined the role of changing family structure in China’s dazzling developmental advance over the past four decades. But there is good reason to suspect that family dynamics are integral to the propitious properties of the much-discussed “demographic dividend” in China and other Asian venues. If so, the family would be a crucial though unappreciated element in contemporary China’s socio economic rise, and this unobserved variable may require some rethinking of China’s modern development, both its recent past and its presumed future.

3) Although China has been living through what might be called a “golden era of the extended family,” this pattern of deep kin networks is going to end in the next few decades. Eberstadt and Verdery write:

The number of living cousins for Chinese under age 30 is about to crash. Just three decades from now, young Chinese on average will have only a fifth as many cousins as young Chinese have today (Figure 4). By 2050, according to our estimates, almost no young Chinese will live in families with large numbers of cousins (Table A4). Between now and 2050, the fraction of Chinese 20-somethings with 10 or more living cousins is set to plummet from three in four to just one in six. …

By then [2050], a small but growing share of China’s children and adolescents will have no brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles, or aunts. Still more sibling-less young people will have just one or two such kin. Thus, a significant minority of this coming generation in China—many tens of millions of persons—will be traversing life from school through work and on into retirement with little or no firsthand experience of the Chinese extended family, the tradition hitherto inseparable from China’s very culture and civilization and experienced most acutely in fullest measure in the decades just now completed.

These kinds of deep demographic changes are likely to have momentous effects. For example, the Chinese government has been able to rely on extended family networks to a substantial extent to look after children, the elderly, or the disabled. It has been able to rely on family networks to spread information about available jobs, useful skills, and possible destinations. People’s family networks have been in some cases leveraged into political networks and even to mechanisms for social control. But Eberstadt and Valery's discussion suggests that China’s extended family networks are about to diminish sharply, and the functions they have served will be diminished as well.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest