Comments

- No comments found

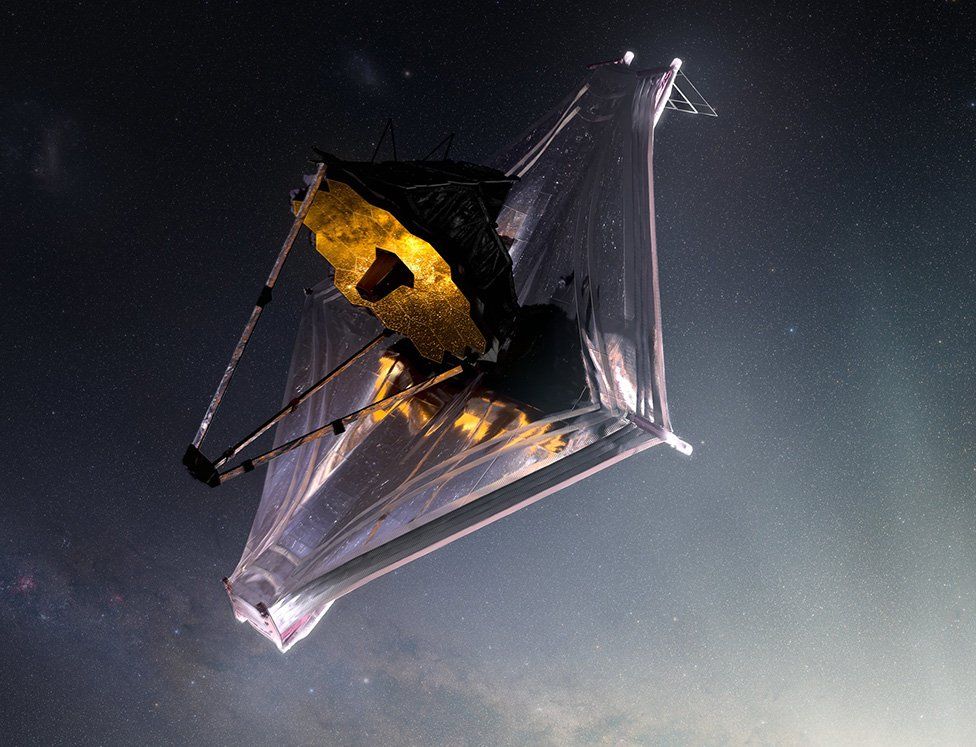

Space enthusiasts got the best Christmas present ever in 2021 — the successful launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

This orbital telescope will serve as the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which launched in 1990, and in April will have spent 32 years collecting some of the most iconic images of the universe that we call home.

In spite of decades of reliable service, Hubble is starting to succumb to the rigour of time spent in outer space, and we needed a replacement. This is where JWST comes in. Now that the telescope is in orbit, how did we get here?

Source: NASA

Setting up an orbital telescope isn’t something that happens overnight. The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope is a project nearly three decades in the making. This telescope is the result of a massive collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

The Hubble Space Telescope launched in 1990, but even then, scientists were working to determine what was going to come next. Hubble was originally expected to last 15 years and has more than doubled that estimate, with experts now anticipating it will continue to function beyond 2030 barring any unforeseen complications.

In 1996, astronauts and astronomers came together to submit a recommendation that NASA begin working on a telescope that could capture infrared images instead of just using a digital imaging camera like the one currently in orbit. In 1997, NASA agreed, planning to fund the project as well as the necessary studies to improve and perfect the technologies that would be needed for the project to succeed.

In 2002, the telescope officially received its name. It is named after James Webb, the NASA administrator who worked to develop the Apollo program that took humankind to the moon.

While NASA may have agreed to fund the project in 1997, construction of the JWST didn’t begin until 2004. A year later, it was decided that the ESA’s Centre Spatial Guyanais (CSG) facility in French Guiana would be the perfect launch site, and the Ariane 5 rocket the ideal launch vehicle. The development process continued through the 2000s and into the 2010s. By 2011, the massive mirror that would be used to collect the infrared data from celestial bodies was ready and could be assembled with the rest of the telescope.

2012 and 2013 saw engineers from all three participating space agencies working together to build the individual components of the telescope, as well as the scientific instruments that would allow it to study the universe and send information back home to teams on earth.

In 2017, all the assembled pieces were sent to the Johnson Space Center in Houston for final testing and assembly. The telescope and all its assembled pieces were in the middle of a 100-day test that used artificial vacuums and frigid conditions to test the device’s ability to survive in deep space.

In the middle of this test sequence came Hurricane Harvey, the devastating storm that caused widespread flooding and billions of dollars in damage throughout the Houston area. In spite of these challenges, JWST passed with flying colours — but the creation of this telescope hasn’t been without its own series of hurdles.

Hurricanes, design challenges, budget cuts, and the COVID-19 pandemic have all interfered with the James Webb Space Telescope launch over the years. Believe it or not, NASA initially hoped to launch the telescope in 2007, but the costs were beginning to pile up and they had to rethink the entire design in 2005, essentially sending them back to the drawing board. They tried again to be ready to launch by 2016 but ran into construction problems that caused further delays.

The much-anticipated telescope was finally fully assembled and ready for launch in 2019 and was scheduled for a 2020 launch — and then a global pandemic shut down the world, pushing the launch back even further.

Finally, on December 25th, 2021, at 7:20 a.m. Eastern Standard Time, the James Webb Space Telescope took flight, launching into orbit and into the history books. For space enthusiasts and NASA fans, it was the best Christmas gift ever. The work doesn’t stop there, however, and the riskiest steps were yet to come.

Within minutes of the successful Christmas morning launch, NASA engineers went to work. At 75 miles up and approximately 206 seconds into the flight, the fairing halves deployed, exposing the satellite to space. Then, 28 minutes later, the James Webb Space Telescope deployed and the real work began.

After launch, there were more than 50 major deployments that had to happen flawlessly to ensure the telescope could successfully reach its targeted orbit. This meant overcoming more than 300 single failure items — more than 300 individual points that could cause the entire mission to fail and cost NASA and the other participating space agencies billions of dollars.

Next came the deployment of the solar array, about 33 minutes after launch. These panels use the sun’s energy to supplement the telescope’s onboard batteries. 12 hours later, Webb began the first of many scheduled burns, firing its thrusters to help it reach the final orbit where it will spend the next decade or more.

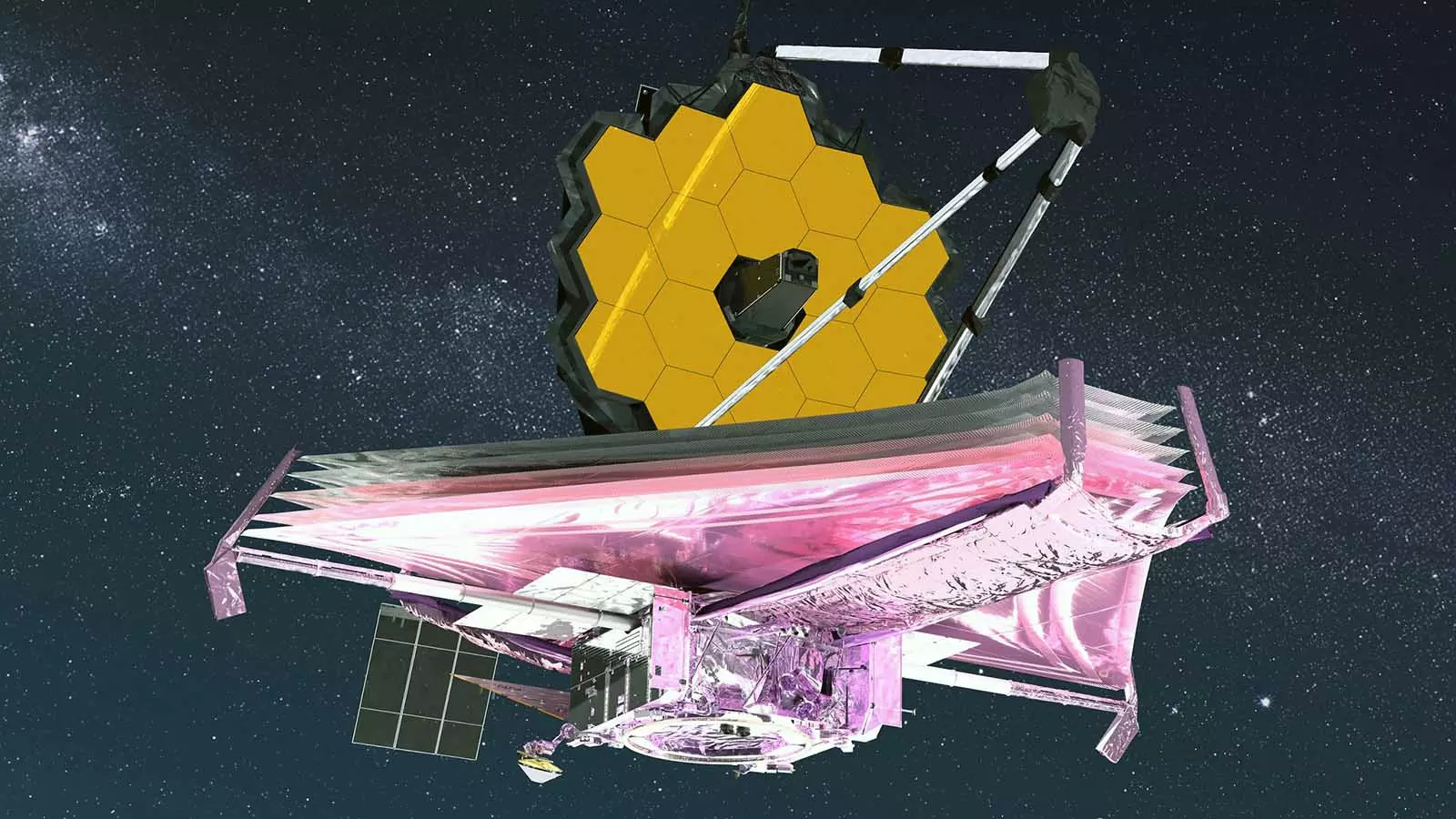

Three days later, on December 28th, the telescope’s sunshield frame began to deploy. When in place, this sunshield will prevent the solar winds and radiation from our own home star from interfering with the infrared data the telescope will collect from beyond the Sol system. On day four, a deployable tower was extended to facilitate the biggest challenge — the deployment of the sunshield.

On Day five, the sunshield cover rolled out of the way and the sunshield could begin to deploy. There are a whopping 107 release mechanisms in this system alone. These all have to fire on cue and work exactly as designed or the sunshield won’t roll out properly. Once the shield is in place, systems will go to work to apply the perfect amount to tension.

Over the next 10 days, more deployments will take place, including telescopes, mirrors, and other necessary tools that will allow the telescope to complete its tasks. It won’t reach its final orbit until 29 days after the launch. The James Webb Space Telescope orbit is targeting the second Lagrange point, L2, which is more than a million miles away from Earth.

In addition to serving as a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, Webb also takes the place of the Spitzer Space Telescope, which could also capture infrared imagery but was retired by NASA in early 2020.

Source: NASA

Right now, NASA and the ground control teams are focused on taking the James Webb Space Telescope through the rest of its elaborate deployments. After that, who knows what the future holds? Webb could potentially change the way humanity looks at the stars, and space nerds around the world are excited to explore what that could mean.

Emily Newton is the Editor-in-Chief of Revolutionized. She is a science and technology journalist with over three years covering industry trends and research.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest