Comments

- No comments found

The prisoner section of the old Wishard Hospital used to be this small window into a world few of us got to see outside of TV crime dramas.

It was a medical theater of loud drunken obscenities, desperate addicts, and beat-up street fighters. It was the temporary refuge of sick prisoners and those acting sick to get a respite from incarceration. It was handcuffs and leather restraints, big security guards, and black polished firearms that match finely shined boots. The clanging of chains grating across bed rails created a strange wind-chime symphony to accompany the electric tones, door alarms, and pagers. When I was a medical student, I always thought our sharp white coats and innocent faces stood out in stark contrast in this ward, something like a daisy on the battlefield of Gettysburg.

“Profeta,” he said abruptly, staring at my name tag. “You related to Al Profeta?” His voice was tense, stern, and accusatory. The other medical students, attending physicians, and residents stood aside, curiously awaiting my response.

“Yeah, I am . . . he’s my uncle,” I said slowly, deliberately, showing not an ounce of fear. Anger welled up inside of me at the thought that this might be one of the sons-a-bitches that shot my uncle Al. That’s when a huge grin broke out over his face, revealing a smile that was missing several front teeth.

“I’m Maurice!” he said jubilantly, with a really big emphasis on the Mo. “I used to be his bag boy; you tell him Maurice said hi . . . you tell him, you hear? I love yo uncle; he’s a good man . . . now don’t you forget . . . that’s Maurice,” again he emphasized the Mo. I patted him on his strapped-down arm and laughed.

“No problem, Mo. I’ll tell him,” I said, walking away smiling.

Once we were out of earshot, my attending physician turned to me and inquired, “A friend of the family?” The other residents and students laughed as we walked down the hall to finish our rounds. I just nodded and grinned.

Uncle Al, was my dad’s older brother by fifteen years, a proud member of Tom Brokaw’s “Greatest Generation.” Some years back, in the corner booth of a Bob Evans, I talked with Uncle Al about his war years, something he had never really done before. He seemed ready . . . and I think perhaps relieved.

Like other young men of the 1940s, he entered the army to save the world from Fascism. Assigned to the 97th Division, he was shipped overseas to serve as a replacement for infantry in the 5307. In time he found himself on a base in northern India, and he was later sent to fight the Japanese along the Burma Road as part of the fabled Merrill’s Marauders. (I only found out recently his entire platoon was awarded the Bronze Star.) This simple man from Indianapolis was soon thrust in the middle of some of the most intense fighting of the South Pacific, assigned to operate a .30-caliber machine gun against heavy Japanese resistance. He’d told me the Japanese would usually attack at night and my uncle would unload his weapon into a sea of tracer fire, unsure of whom he was actually shooting at.

In the morning he would awaken to a field of dead Japanese soldiers.

Over a plate of eggs and buttered toast, he recalled how when night fell, so much changed for the soldiers of the Burma conflict—a kind of comfort to chaos. The sounds of Japanese military vehicles clanging on the cobblestone Burma Road would signal a call to man the .60-caliber mortars. Al and his platoon would rain down a barrage of exploding ordnance toward the sound of the convoys, leaving burned-out Japanese vehicles and the accompanied dead to line the road. Many nights he spent hunkered down in foxholes only to awaken and find that incoming artillery had missed his hole by only a few feet, sparing him from certain death.

“Uncle Al, were you scared? Did you think about dying?” I inquired, looking into his face for some sign of fear or regret that I never saw.

“Noooooo,” he laughed. “I never even thought about getting killed myself. It just didn’t cross my mind.” He took another sip of coffee.

“What about the Japanese prisoners, how were they treated?” I asked. He became kinda quiet in his tone, distant a bit.

“There were no prisoners . . . we killed them all,” he replied matter-of-factly. “We killed them all.”

In some ways he seemed to have a sense of surrendered nonchalance about death. He told me they were just hell-bent on doing their job: showing up, saving the world, and getting the hell back home. Uncle Al, like many of the old-time vets, walked through life with an attitude of “If it’s my time, it’s my time.” They were there to do their duty, to fight for a greater good, and their lives were expendable to achieve it. They knew this and if by chance they survived, it was all the better.

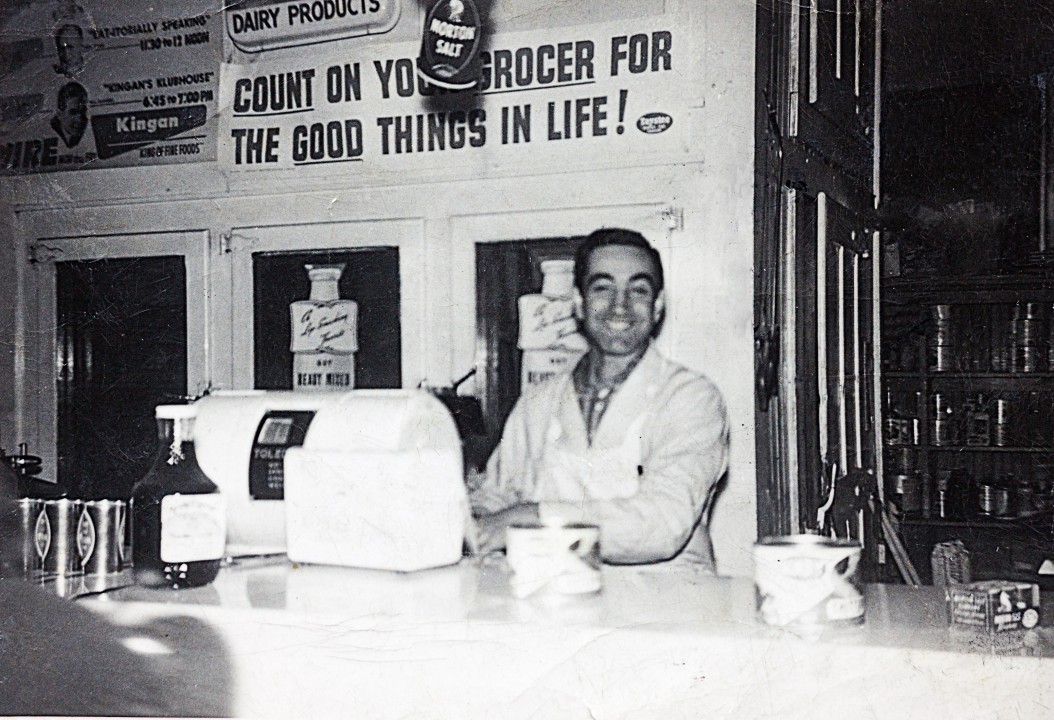

After the war, Uncle Al found himself back in Indianapolis. He didn’t capitalize on the GI Bill and enroll in college, something I think he regretted. Instead, he settled down. In 1950 he married Becky, the girl he met at a bar-mitzvah in Cincinnati. They raised two children: a daughter, Sandy; and a son, Larry. With the help of his father, he opened a small grocery store on the near west side of Indianapolis (near 30th and Rader).

In the ’50s it was a predominantly white, middle-class neighborhood. But in time, that population would move to the north suburbs and Uncle Al was left as the only white grocer in the middle of a working-class, predominantly African-American neighborhood . . . a neighborhood he loved.

A Pepsi Cola sign with its dark letters, “Profeta’s Market,” stood out on the gray cinder block and black tarpaper-roofed store. As the years passed, Al and his wife Becky along with their children became valuable members of the community. He kept his prices fair and perhaps a bit too low, often providing credit to the neighborhood poor. He lived a simple life and enjoyed simple pleasures. Having survived the war, I think he felt, as did most vets, that the rest of his life was like a free dessert. I’m sure he also felt that he had dodged all the bullets and bombs he would see in this lifetime so he might as well relax. On Halloween night, in 1963, he found out he was horribly mistaken.

The “Holiday on Ice” show was in town and Uncle Al, Aunt Becky, my cousins Sandy and Larry had tickets. It was at the Coliseum, still a fixture of the Indiana State Fairgrounds. The show was enjoyable and they certainly could see all the pageantry, but Larry—then twelve years old—was upset that they were seated so high up. He noticed empty seats down a bit lower and implored his parents to move down. I think Uncle Al thought it was like stealing and wouldn’t let him, he had paid for these seats. They stayed put and they stayed alive.

For the 4,000 or so spectators, it was a graceful exhibition of the art of figure skating: smooth, seamless, and free flowing. However, near the end of the show, two explosions—caused by a leaking propane tank in a concession stand that blew up—caused a shock wave through the venue sending bodies and severed limbs flying through the air. This turned the white ice into a frozen lake of charred human remains, concrete, and blood. In all, 74 people died and 400 were injured. The vast majority of the dead and injured came from the very same section where Larry had wanted to sit and had begged his father to move to earlier, the rows which now lay strewn with the mangled and the dead.

As they exited the Coliseum, they passed a man lying near the exit whose legs had been blown off. I imagine that for a moment, Uncle Al was back in Burma, dodging bullets and ducking from mortars. They found a young boy crying hysterically at the entrance, took the child’s hand, and walked all around the Coliseum trying to find his parents. In time, they were found alive and, according to Al, the reunion was as emotional as expected. Over the years Uncle Al reflected very little on his near-miss with death: He went on with his life. Grateful to be alive, he returned to the responsibilities at hand: raising his children, being a good husband and a good Jew, a good person, and running an honest business.

He unknowingly had a tremendous impact on me. When I was a kid, I loved it when Dad would take me to Uncle Al’s store. He had this old potbelly stove at the entrance. The wooden floors smelled like cold meat fat, and there was one of those pop machines as you entered that had a tall line of glass bottles. You put your coins in and pulled at the rough bottle top with a great deal of force to remove the sodas from the rollers. If successful, you were rewarded by an ice-cold grape or orange Nehi; it was frigid, frosty, and very satisfying, much like my Uncle Al.

I was amazed at how he seemed to know everyone’s name that came into his small grocery. He would always be engaged in some bit of sarcastic banter with his customers and it was so clear to me, even then as a child of nine or ten, that everyone liked—no, loved—this man. For years, Uncle Al ran this small dilapidated store, scraping out a living that he supplemented by running numbers and buying and reselling lottery tickets from Illinois; something that, in all honesty, served as a form of entertainment for the community. Even though the neighborhood experienced the ravages of urban decay, drugs, and crime, he chose to stay and fight the good battle. The honest, hard-working people in the area depended on him for their groceries and the simple home supplies and hygiene items of everyday living. The big grocery chains weren’t climbing over each other to build in the area, and most of the people relied on public transportation to get them to and from work, and to their doctors and banks. Having to take the bus for a simple carton of milk would have been both expensive and inconvenient. But they could walk to his store, interact with their neighbors, and feel part of a community, of something greater than themselves. It was not just Profeta’s Market; it was Everyone’s Market. But in 1981, all of that changed when three men from Chicago shot Uncle Al, beat up his son, and robbed the store and the neighborhood of two of their most prized assets: my uncle and their market.

Al later told me, “Larry and I were the only ones in the store and they came in and shouted, pointing guns, This is a holdup . . . open the safe! Well I start laughing and say, What safe? We hardly have any cash.”

A friend had heard the commotion over an open phone line and notified the police. They were there in minutes, surrounded the store, and called the robbers out. Unfortunately one of them panicked, pushed my uncle to the door as a human shield, telling the police to get back. Then, for no reason at all, in clear view of his own son, he shot Uncle Al in the side with a .357 Magnum revolver. The bullet passed clear through him, knocking him to the ground. This good man who survived WWII, an explosion at the Coliseum, was now dying on the floor of his own store in the middle of America’s heartland thousands of miles from the Burma Road.

The police lobbed teargas into the small store, and the robbers were arrested. Al was evacuated by medics to one of the regional trauma centers; he told the paramedic he didn’t think he was going to make it. At the time I suspect the medic probably thought the same thing. Years later I took care of one of the police officers who helped my uncle that day. “We used to go out for lunch every week for years . . . he never told you?”

“Oh he told me . . . he loved it.”

I used to be convinced that Uncle Al was unbreakable. Not only did this man survive, but the .357-caliber slug missed all his vital organs as it passed clean through him. However, it did leave him with nerve damage, some chronic pain, and was enough of a disability that he could no longer carry on as the neighborhood grocer. Larry tried to maintain the store, but the work and frustrations of a small grocery were just not worth the effort. Thus, these three outsiders, who knew nothing of this man and his community, ended up stealing from everyone who lived there. Two years later, with a mixture of sadness and relief, Al closed the shop, gave all the food away to his former customers, and walked away with his memories and his life.

Al was an amazing man. I am not sure there is anyone who appreciated being alive as much as he did. His face was almost frozen in a permanent smile. I tried to mimic it once, and it actually hurt, like trying to do a hundred push-ups. My facial muscles have just not been cut and chiseled with the same degree of life optimism as his, though I am still trying to exercise those muscles on occasion.

Uncle Al died some years back at the age of ninety-one. He once told me his goal was to be the oldest living WWII vet. It didn’t happen, but he carried on with his simple life and deep friendships. In his waning years he worked a few shifts in the old neighborhood at one of the area liquor stores, just so he could see some of his former customers. Once a week he’d have lunch with the detective who pulled him from the store. He’d work out a few times a week at one of the local health clubs, and every Sunday you could find him and his friends, of which there are many, bantering about at Bob Evans Restaurant over breakfast. A few years before he finally passed, he drove his car underneath a semi-trailer, shearing off the roof; but, of course, he walked away without a scratch.

As his body faded, he found his way into the local Jewish nursing home and soon was given the moniker “Mayor of Hooverwood.” He knew everyone, and everyone knew him.

I asked him once if he had any regrets in his life and he said, “Just one: that my wife is not alive.” Her passing, his wartime experience in Burma, almost dying on the floor of his market, and the Coliseum tragedy, all seemed to have had a profound influence on a very special task he embraced later in life.

Al had taken on the sacred role of becoming a member of the Chevra Kadisha, Jewish men and women responsible for the ritual cleansing of the bodies for burial. It is considered one of the greatest mitzvahs (good deeds) in Judaism because the dead cannot thank you. It is a wonderfully gentle and fulfilling deed. I have even done it myself. They bathe and clean the body, scraping and removing all the dirt; they chant the customary prayers that have been recited for thousands of years, gently wrapping the hands, the feet, and the body in soft white cotton cloth. I think it was his private way of thanking God for life, giving back to a God who has given him so much and had spared his own life so many times.

Most people now know me as the ER doctor or the writer, but perhaps the thing I’m most proud of is when someone hears my name—typically an older African-American patient or their family—and asks,

“Profeta . . . are you related to Al Profeta?”

“I am,” I reply. “Did you used to live near 30th and Rader?”

They always smile and say, “Sure did, used to go to his store.” This is usually followed by “He was a good man,” or “What’s his son up to?” Or perhaps, “I remember when he was shot . . . what a shame.” Then, of course, when he was alive, it was always followed by “Ask him if he remembers . . .” or, “Tell him I said hello.”

I give them an exaggerated, squinty-eyed smile and ask, “Don’t I look like him?” They laugh and nod and I find myself thinking,

I need to exercise those muscles more.

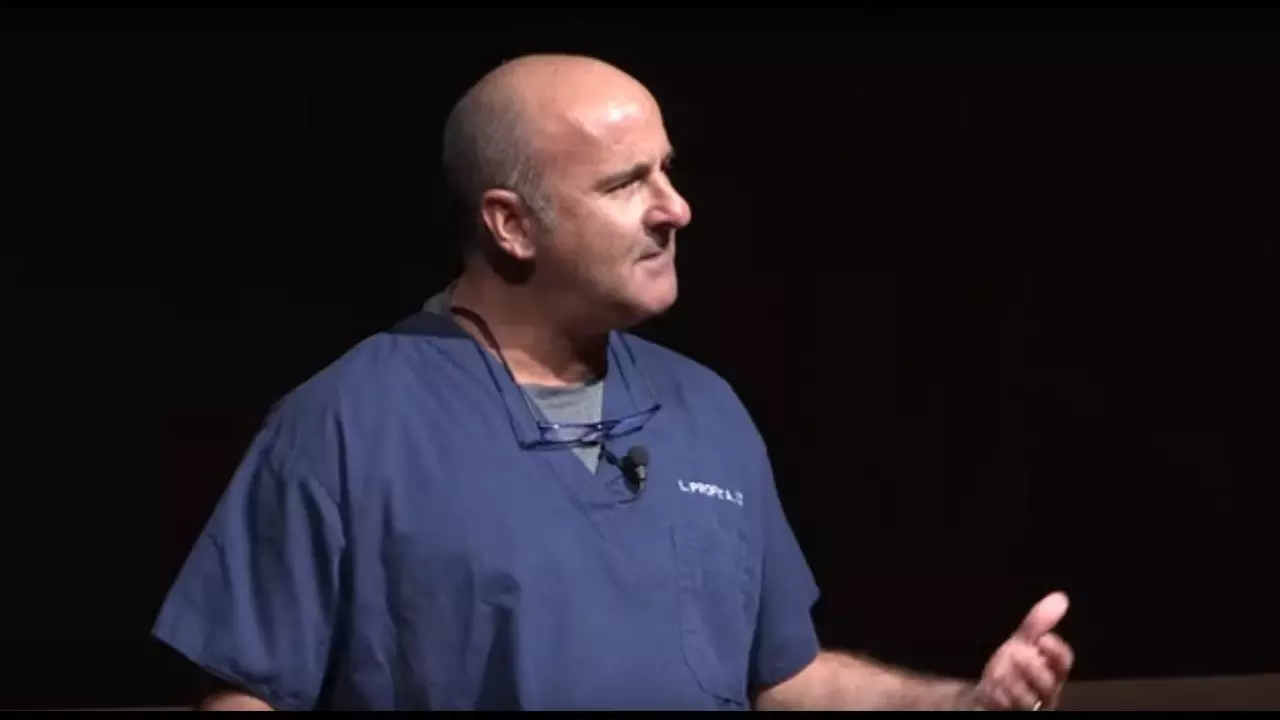

Dr. Louis M. Profeta is an emergency physician practicing in Indianapolis and a member of the Indianapolis Forensic Services Board. He is a national award-winning writer, public speaker and one of LinkedIn's Top Voices and the author of the critically acclaimed book, The Patient in Room Nine Says He's God. Feedback at louermd@att.net is welcomed. For other publications and for speaking dates, go to louisprofeta.com. For college speaking inquiries, contact bookings@greekuniversity.org.

Dr Louis M. Profeta is an emergency physician practicing in Indianapolis. He is one of LinkedIn's Top Voices and the author of the critically acclaimed book, The Patient in Room Nine Says He's God. Dr Louis holds a medical degree from the Indiana University Bloomington.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest