Comments

- No comments found

At what age does the average person retire in high-income countries? How long is the average period of retirement?

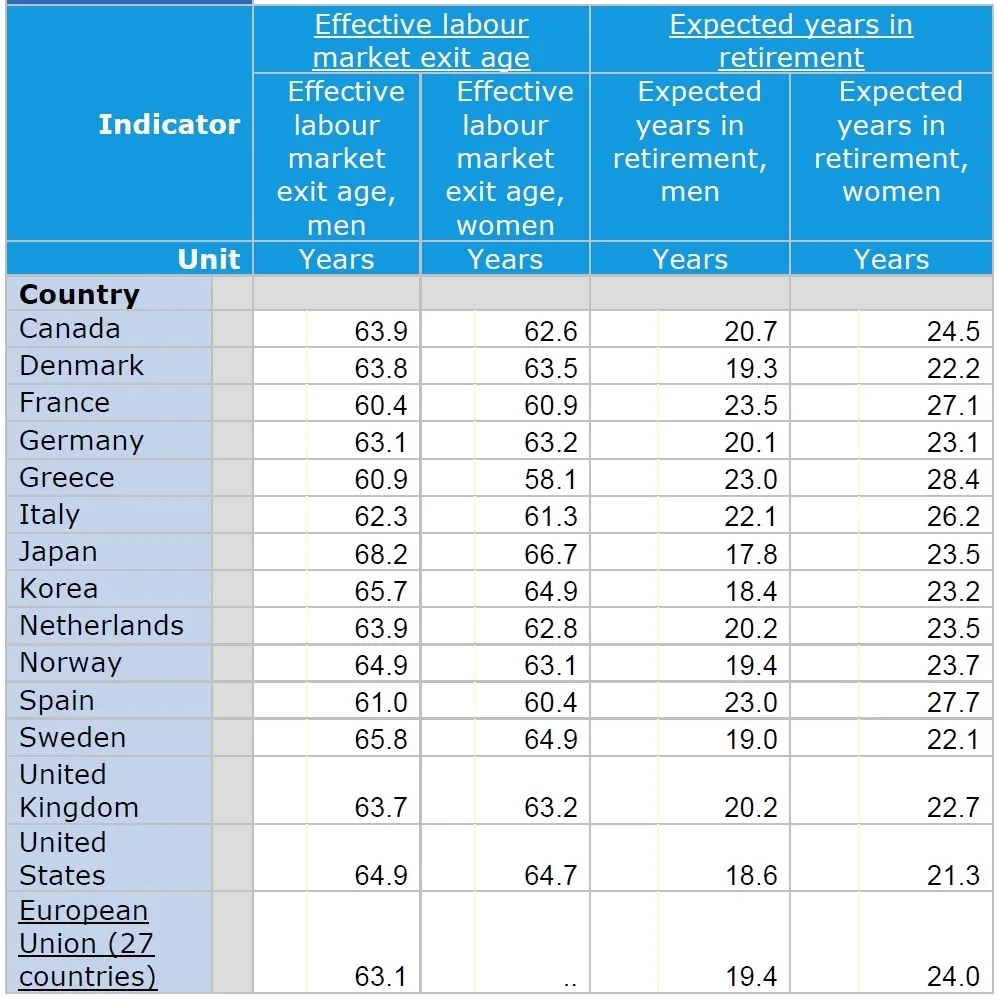

The OECD collects this information. Here’s a trimmed down table with a selection of countries.

You can see from the first two columns of data that the average age of labor market exit for US men and women is a shade under 65 years. This is lower than Japan and Korea, and interestingly, lower than Sweden as well. The countries with the earliest average ages of labor market exit seem to be France, Spain and Greece at less than 61 years, with Italy also on the low side.

The last two columns of data show expected years in retirement. For the United States, this is 18.6 years for men and 21.3 years for women, mostly reflecting the longer average life expectancies for women. The shortest expected retirements are in Japan and Korea. Interestingly, Sweden has a later average age of retirement than the US but also a longer expected retirement–which is possible because of longer life expectancies in Sweden. The longest retirement periods seem to be in the countries with the lowest retirement ages, like France, Greece, and Spain, where it is common for men to have 23 years in retirement and women 27 years.

Over time, the average age of retirement in the US has followed a U-shaped pattern over the last 50 years, first dropping by about three year and then rising back close to the earlier level. For men, the OECD data shows that the average age of retirement for men was 65.5 years in 1970, 63.8 years in 1980, 62.4 years in 1990, 62.5 years in 2000, 62.9 years in 2010, and then 64.9 years in 2020. For the expected time in retirement, the US follows a substantial rise from 1970 up through 2012, but a gradual decline since then. For men, the OECD data shows 12.8 years of expected retirement in 1970, 15.0 years in 1980, 17.0 years in 1990, 18.2 years in 2000, 19.6 years in 2010, and then–after peaking at 20.1 years of expected years of retirement in 2012–a gradual decline to 18.6 expected years of retirement in 2020.

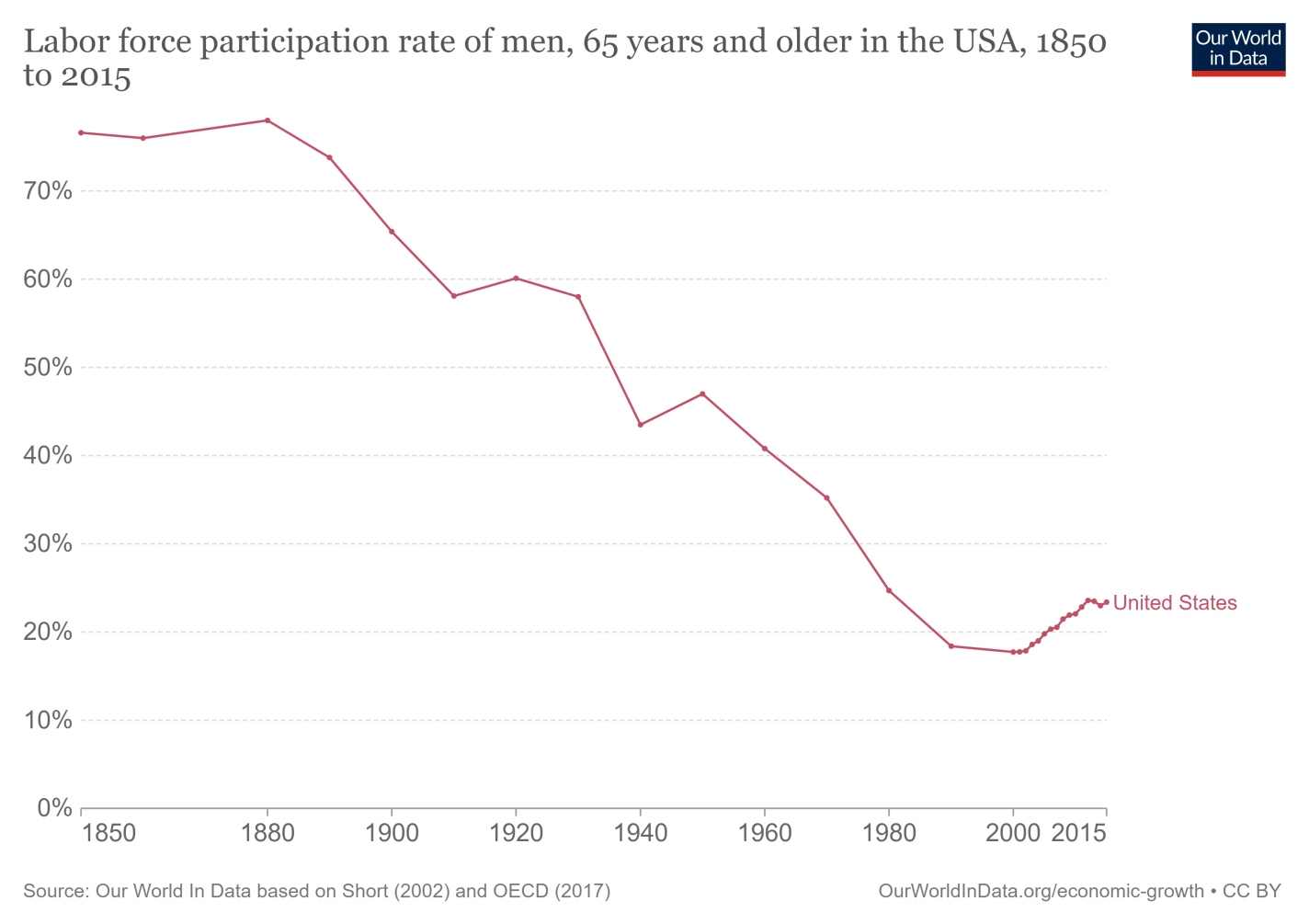

In a big-picture sense, this is consistent with a long-term pattern of US men over age 65 decreasing their labor force participation in the long run, but with an upward shift in labor market participation in the last 20 years or so. From the Our World in Data website:

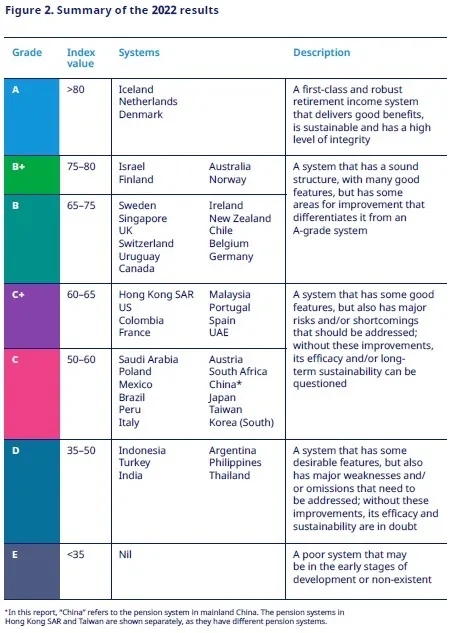

Given that the US has a relatively late age of expected retirement and relatively short period of expected retirement, one might expect that the US Social Security system of government pensions would be in relatively good financial shape compared to some other countries, but this doesn’t seem to be correct. Consider this table from the Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index 2022, which ranks pension systems across 44 countries for adequacy, sustainability, and integrity. (“Integrity” refers to a combination of issues related to regulation, governance, protection, communication, and operating costs.) The US system does fairly well for adequacy, but not so well on the other measures. Of the countries listed above, Netherlands and Denmark are thought to be grade A systems. The US overall category with countries like France and Spain. Those countries rank higher than the US on “adequacy” of benefits, with their lower retirement ages and longer expected periods of retirement, but rank lower than the US on the financial “sustainability” of the benefits.

As the US deals with the financial consequences of an aging population, it seems appropriate that part of the answer will involve people working longer on average. But other parts of the answer will also involve additional financing for the system as a whole and additional support for the elderly poor.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest