Comments

- No comments found

For economists, r* refers to the “natural rate of interest” that emerges from economic theory.

It’s the “Goldilocks” interest rate that is not too high and not too low: that is, the interest rate that would occur “naturally” in the economy when the economy is at potential output and inflation is stable. A “tight” or restrictive monetary policy would involve the central bank setting interest rates above r*; conversely, a “loose” or stimulative monetary policy would involve the central bank setting interest rates below r*.

It would obviously be useful to have clear estimates of r*. Do such estimates exist? Gianluca Benigno, Boris Hofmann, Galo Nuño, and Damiano Sandri investigate in “Quo vadis, r*? The natural rate of interest after the pandemic” (BIS Quarterly Review: Bank for International Settlements, March 2024, pp. 17-30). For those whose Latin is rusty or nonexistent, like me, a modern translation of “quo vadis” would be “where are you going,” while an older translation would be “whither goest thou.” The author write:

[We are] assessing the natural rate of interest, commonly known as r*, in the post-pandemic era. The natural rate refers to the short-term real interest rate that would prevail in the absence of business cycle shocks, with output at potential, saving equating investment and stable inflation. Hence, the natural rate serves as a yardstick for where real policy interest rates are headed. It is also a benchmark for assessing the monetary policy stance “looking through” business cycle fluctuations. … Together with the long-run inflation rate, defined by the central bank inflation target, it pins down the long-run level of the nominal policy rate.

The challenge is that it’s not obvious how to estimate r*. After all, historical data tells us what interest rates were as the economy and monetary policy fluctuated, but for r*, you need an estimate of what the interest rate would have been if the economy had remained at potential GDP, with low unemployment and low inflation. It’s also quite possible that r* shifts over time, which makes estimating it even harder. Moreover, in a globalized capital market, r* will be affected by global factors, not just factors within the domestic economy. The BIS authors describe the main factors that would influence the natural rate of interest:

The natural rate is commonly thought to be determined by real forces that structurally affect the balance between actual and potential output, or equivalently

between saving and investment. Specifically, factors that increase saving or decrease investment lower the natural rate. These include potential growth, demographic trends, inequality, shifts in savers’ and investors’ risk aversion and fiscal policy. Lower potential growth lowers investment by reducing the marginal return on capital and increases saving by lowering expected income. Longer life expectancy raises savings as households need to support a longer retirement. A lower dependency ratio – reflecting a higher share of working age people in the population – increases saving as those in the workforce typically save more than the young and the elderly. Higher inequality raises savings as richer households save a larger share of their income. Higher risk aversion induces higher saving, in particular in safe assets, and at the same time lowers investment. Finally, persistent fiscal deficits reduce aggregate savings. In a globalised world economy, with free capital flows, the same considerations apply but at the global level.

For example, a common set of beliefs about r* in the last decade or so is that there has been a “global savings glut”–and a higher supply of savings will tend to drive down natural interest rates. The global savings glut comes partly from very high savings in countries like China, partly from greater inequality of income and wealth because those with higher incomes and wealth tend to save more, and from other factors as well.

Economists seeking to estimate r* usually build a model of the economy. They set up the model so that it does a reasonably good job of following what happened in the actual economy. Then, when the economy is out of balance, the model can be used to project what the interest rate would be if the economy moves back into balance. (In a very broad sense, this is like looking at a single market that has been shocked by events–like the crop harvest problems in the cacao market that have driven up chocolate prices–and projecting the price to which cacao will return when the shock is over.)

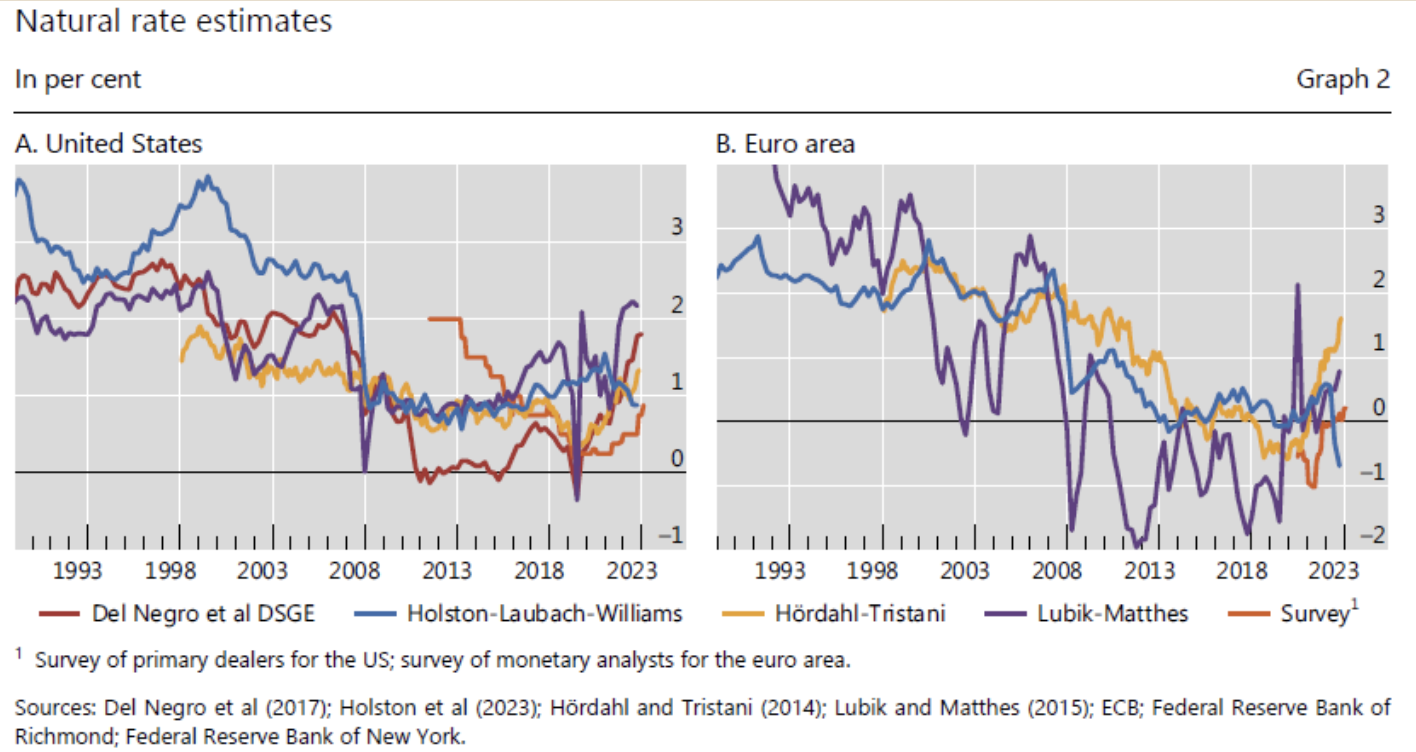

The BIS economist discuss estimates of r* based on several modeling approaches: a “semi-structural” model, a “vector autoregressive” model, a “dynamic stochastic general equilibrium,” a model that looks at differences between shorter-term and long-term interest rates and how they evolve over time, and plain old surveys of key market participants. I will not try to explain the differences across these models here: suffice it to say that they are built on differing theoretical perspectives. Here’s a set of estimate of r* for the US dollar and for the euro:

As you can see, estimates of the natural rate of interest have declined over time. For the US, estimates before the Great Recession of 2008-09 were in the range of 2-3%. Since then, estimates were often 1% or lower–with a noticeable upward movement in the last year or so. The estimates for the euro area have a broadly similar movement from higher to lower, but a number of the estimates suggest that the natural interest rate in euro markets involved a negative interest rate for substantial parts of the last few years, a policy recommendation that raises some complications of its own.

For present purposes, the main concern here is whether these estimates of r* can offer practical guidance on whether, say, the Fed should be raising or lowering interest rates. It seems dubious. It’s not just that the range of estimates for the US market is wide, which it is, but also that each of these individual estimates is not precise, either, but represents a range of uncertainty. Moreover, the basic theory of the natural rate of interest r* suggests that it should be independent of monetary policy, because it represents the interest rate for an economy in balance. But is it really just a coincidence that estimates of r* plunged after the Great Recession, when monetary authorities were cutting interest rates? Were central banks cutting interest rates because r* had fallen, or do the estimates of r* from the economic models reflect to some extent that central banks had cut rates? It’s not easy to know.

The BIS authors argue: “The uncertainty surrounding r* suggests that it is a blurry guidepost for assessing the monetary policy stance and hence the tightness of monetary policy, in particular at the current juncture. In this context, it appears advisable to guide policy decisions based more firmly on observed inflation rather than on highly uncertain estimates of the natural rate.”

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest