Comments

- No comments found

On the one hand, it seems terribly important that global food supply increase dramatically in the next few decades, to feed the hungry around the world as the global population rises.

On the other hand, obesity is a huge and ongoing health problem around the world, even in many countries that do not have high income levels. And on yet a third hand, food production around the world is often a major contributor to environmental degradation, being related to issues including water pollution, deforestation, pesticides that linger in the ecosystem, and release of greenhouse gases.

A desirable path for the future of global food production will take all of these into account. The Credit Suisse Research Institute takes a shot at reconciling them in “The Global Food System: Identifying sustainable solutions” (June 2021). Let’s start with a description of the competing priorities:

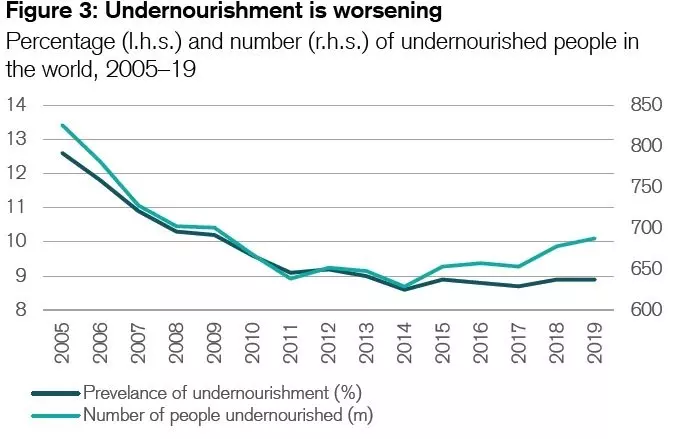

About 9% of the global population, consisting of about 700 million people, is undernourished.

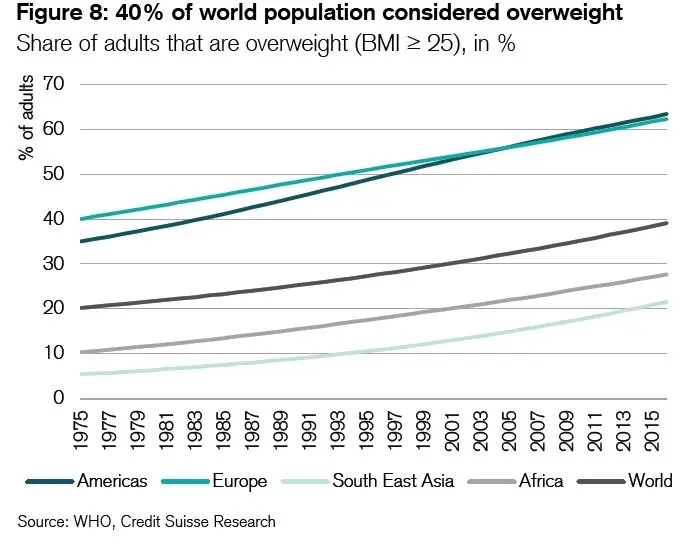

About 40% of the world population is overweight.

When it come to environmental issues the report notes:

Food production and consumption already contribute well over 20% to global greenhouse gas emissions and account for more than 90% of the world’s freshwater consumption. After reviewing the environmental footprint of all major food groups, we conclude that the current situation is likely to worsen significantly unless action is taken. The likely growth in the world’s population to around ten billion people by 2050 coupled with a further shift in diets, especially across the growing emerging middle class, could increase emissions by a further 46%, while demand for agricultural land could increase by 49%. … [T]he growth in agricultural land seen to date has come at the cost of greater deforestation. Data from Global Forest Watch suggest that annual tree loss cover has increased from around 14 million hectares in 2001 to around 25 million hectares in 2019 … . The FAO indicates that some 420 million hectares of forest has been lost since 1990, which is the same as roughly eight times the size of France or 50% of the USA. Deforestation not only releases stored carbon dioxide, but

also reduces the ability to capture future carbon releases. Furthermore, it contributes to a loss in biodiversity and puts pressure on soil quality, which in turn is seen as contributing to the risk of drought and floods.

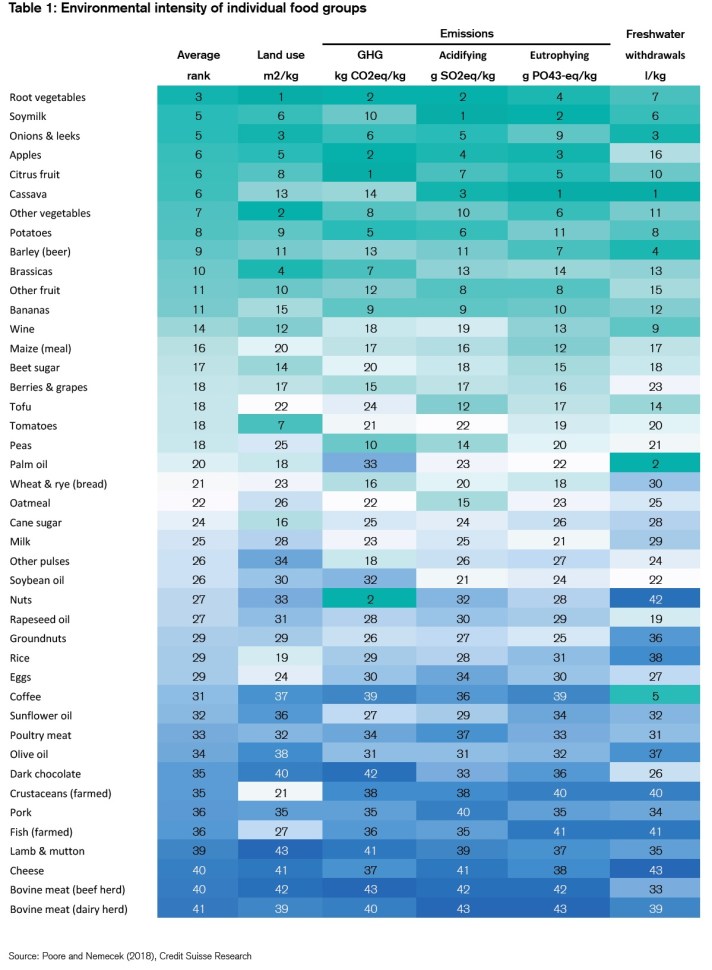

What’s the pathway through this maze of concerns? Start with the environmental issue. Here’s a table that tries to compare the environmental costs of a variety of foods. I’m sure one can quarrel with the details, but the broad nature of the overall rankings is clear. Vegetables and fruits in general have lower environmental effects. Meat and dairy, and beef in particular, have the highest environmental effects.

As it turns out, many of the human health issues of obesity are related to consumption of meat and dairy, and more broadly to limited consumption of vegetables and fruits. And when it comes to expanding calorie outputs for a growing world population, it’s probably efficient to do so by expanding non-meat alternatives.

Along with a shift away from meat in general and beef in particular, there are some other useful steps to be taken. One is to take food waste seriously as a policy concern:

More than 30% of food produced is either lost or wasted. By way of example, around USD 408 billion of food produced in 2019 went unsold or uneaten. The FAO estimates the economic, environmental and social costs associated with food waste at USD 2.6 trillion. Eliminating food waste in the United States and Europe alone would add 10% to the world’s available food supply. Solutions need to focus across the entire supply chain as about 50% of food is lost in the production and handling phase, while 45% is wasted in the distribution and consumption phase.

The agenda for reducing food waste often focuses on issues like improved storage, faster transportation, and recognizing alternative uses that will give a stable shelf-life to food that would otherwise have spoiled. To cite one of a number of examples from the report: “Baldor, a major food processor that makes products like `baby’ carrots (i.e. regular carrots carved into tiny pieces), turns fruit and vegetable scraps into multiple products: some fruit scraps go to juice companies, vegetable scraps go to chefs for use in stocks, a mix of vegetables are dried and crushed into a flour that can be used in place of wheat, and other scraps are used in meal kits that include veggie noodles.”

Another set of options involve bringing the technology revolution to farming. For example, the report suggests that “precision farming through the use of artificial intelligence, drones, autonomous machinery and smart irrigation systems could yield productivity increases of 70% by 2050.”

Another option is “vertical farming,” “which is an indoor approach consisting of controlling all environmental factors such as light, humidity and temperature, with the aim of producing more

food by harvesting crops vertically. This concept enables the cultivation of various crop types

ranging from leafy greens and tomatoes to herbs and flowers, as well as microgreens, and fulfills environmental, social and economic goals. … According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, it is possible that, by 2050, 80% of the food consumed in urban areas could be produced using vertical farming technologies.” In fact, Netherlands is the world’s #2 exporter of agricultural products by value thanks to its embrace of these kinds of technologies.

In thinking about a shift away from traditional meat, several options have been getting a lot of attention. “[L]ivestock provides just 18% of calories consumed by humans, but takes up close to 80% of global farmland.”

One option is “plant-based meat” products like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. “The reason for supporting the growth of plant-based meat is that it uses 72%–99% less water and 47%–99% less land than traditional animal-based meat. In addition, water pollution is substantially lower, whereas GHG emissions are also between 30% and 90% lower. One other aspect worth highlighting is that plant-based meat does not require the use of antibiotics, which is very common with animal-based meat production.”

Another option is “cultivated meat,” which is meat grown directly from cells. “For example, cultivated meat has a feed conversion ratio (kg in per kg out) that is more than seven times higher than that of beef cattle and almost six times higher than that of pork.” Yet another option is the use of fermentation: “Alternative proteins can also be produced through fermentation processes using microorganisms. Traditionally, fermentation has been used to make beer, wine and cheese, and the same process can be used to improve the flavor of plant ingredients. … Biomass fermentation has the clear advantage of speed. The doubling time of the microorganisms used is hours compared to months or longer for animals.”

When thinking about these alternative products, I always add two thoughts in my own mind. First, it seems likely that the potential productivity gains for these products are high, which suggests that it will be possible to drive down their price dramatically. If a plant-based “hamburger” at the fast-food drive-through was half the price of ground beef, or less than half the price, my guess is that I wouldn’t be alone in being willing to make the shift. Second, as long as we think about these products as meat substitutes, I suspect they will feel unsatisfying. But it’s relatively straightforward to tinker with the taste of plant-based products, and eventually some of these products will be created that aren’t viewed as substitutes for something, but instead their popularity will stand on its own.

Reports like this one often jump pretty quickly from a list of problems to discussions of government regulation and requirements, and this report is no exception. Many jurisdictions are passing taxes on sugared drinks; is a tax on meat next? I’m agnostic on much of this policy agenda, which is to say that I’ll judge the individual proposals as they come along. I suspect that the pull and push of demand and supply will bring about many of these changes, as the world moves toward feeding a few billion more people at a time of rising environmental concerns. Thus, I tend to see this report as a forecast of where we are already heading.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest