Comments

- No comments found

The actual economic recession connected with the COVID pandemic turned out to be extremely short, lasting only during March and April 2020.

Of course, the dislocations and restrictions associated with the pandemic in areas like health, jobs, sectors of the economy, online education, and travel have continued in various forms since then. But focusing on the economic issues, what have we learned? Recession Remedies: Lessons Learned from the U.S. Economic Policy Response to COVID-19, edited by Wendy Edelberg, Louise Sheiner, and David Wessel and freely available online, provides nine essays on different aspects of the economic policy response.

Here’s an overview of some of the issues from “Lessons Learned from the Breadth of Economic Policies during the Pandemic,” by Wendy Edelberg, Jason Furman, and Timothy F. Geithner.

The U.S. economy experienced a V-shaped recovery of a type not seen in recent recessions. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) exceeded its pre-pandemic level by the second quarter of 2021 and was close to pre-pandemic estimates of potential by the fourth quarter of 2021. The unemployment rate ended 2021 below 4.0 percent, just slightly above where it was two years earlier, prior to the pandemic. …

Overall, the United States’ fiscal response appears to have been much larger than the response undertaken by any other country; this was especially true in 2021, when fiscal policy was as supportive as it was in 2020. The U.S. GDP recovery has been among the strongest of any of the advanced economies, but the U.S. employment recovery has been among the weakest; this suggests that both the size of the response and, perhaps, its character and pre existing institutions all matter. …

The economy experienced major side effects from the pandemic and associated policy response, most notably the highest inflation rate in 40 years, far outpacing the increase in wages and leading to the largest real wage declines in decades. In addition, the U.S. government incurred substantial debt during the pandemic. With the expiration of most forms of fiscal support, real household income is likely to be lower in 2022 than in 2021 and could well be below its pre-pandemic trend. As a result, poverty is on track to rise in 2022. Moreover, inflationary pressures and the efforts to moderate those pressures might bring an end to the expansion.

Ultimately, the economic policy response to the COVID-19 recession should be judged not just by its consequences in the spring of 2020, not what happened over the next two years, but also by the longer-term effects, and whether the response will prove to have contributed to a stronger and more sustainable economy going forward. …

Here is a non-exhaustive list of the lessons I took away from the essays in the book. I’ll list the table of contents for the book below.

1) When the pandemic recession first hit, the effects were severe and there was no good sense of how long it might last. Thus, the priority of economic policy was to go big and fast: in particular, certain policies spent large chunks of money in rebates, stimulus, unemployment insurance, and others. Some of these handed out money in essentially untargeted ways. As one example, the Paycheck Protection Program funneled several hundred billion dollars to businesses with fewer than 500 employees, with the idea that it would protect jobs, but given that it was essentially free money from the government, a lot of it ended up going to the owners of the firms. Economic policy in early 2020 faced a choice between targeting and speed, and mostly chose speed.

2) The early goal of economic policy in March and April 2020 was not really seeking to help the economy recover: it was to help large parts of the economy shut down to minimize the chance of the pandemic spreading, but in a way that tried to support income.

3) The economic recovery from the pandemic happened faster than many people expected. Thus, when Joe Biden took the presidential oath of office in January 2021, there was a widespread sense that additional fiscal stimulus was needed. But the recession had ended in April 2020, and the vaccines had arrived. In fact, the US economy in early 2021 was in a quite different place from a year earlier. In a crisis, there is sometimes a sense that “you can never do too much.” But Continuing and extending federal support payments in 2021, as if it was still 2020, was a mistake and a contributor to the launch of inflation.

4) Compared to EU experience, the job market in the US had a much steeper fall. One reason was that US payments to unemployed workers were very high, sometimes more than 100% of previous wages, while payments in European countries typically replaced about 70-90% of lost income. Second, European countries emphasized “short-time work” policies that are like part-time unemployment. The idea was that instead of having a company lay off some workers completely, the company could reduce the hours of all workers, with the government then making up much the difference in pay. Such policies seek to preserve employer-employee ties, with the idea that such ties make it easier to return to work–and much easier for the employer to require that employees return to their jobs. There are longstanding arguments about the merits of subsidizing workers via unemployment insurance or subsidizing jobs with short-term work programs. There is probably a role for both approaches–but during a short, sharp pandemic shock, short-time work has some real benefits.

5) Near the start of the pandemic recession, there was concern that state and local governments might face severe strains, but the eventual result was more mixed. Louise Sheiner writes:

So, what happened to state and local government revenues, employment, and spending during the first two years of the pandemic? Revenues did not decline nearly as much as had been first feared and federal aid was more than sufficient to offset any revenue losses in every state. Nevertheless, state and local government employment declined sharply, and the decline has been quite persistent: employment by state and local governments in February 2022 was three percent below the January 2020 level. Looked at another way, in February 2022, the state and local sector accounted for 23 percent of the shortfall in U.S. employment from its pre-pandemic trend. … Overall, it seems clear that the employment losses vary a lot by state in ways that cannot fully be explained. … [G]enerous federal aid to states was clearly not sufficient to reverse or prevent all the employment losses. One important question is, why not? What did state and local governments do with the federal aid, and why didn’t they use it to increase employment?

6) The vulnerabilities of the US financial system had played a large role in propagating some recent recessions, including the Great Recession of 2008-2010 and the 1991 recession which had some links to the collapse of the savings and loan industry. But in the pandemic recession, the US banking system performed just fine. A large part of that performance was the rules put into place after the Great Recession on the capital and safety standards that banks needed to meet were effective. The Federal Reserve also played a role in extending short-run credit and making sure that financial markets didn’t freeze in place, especially in March 2020, but overall, the story in the financial sector is the success of the earlier reforms.

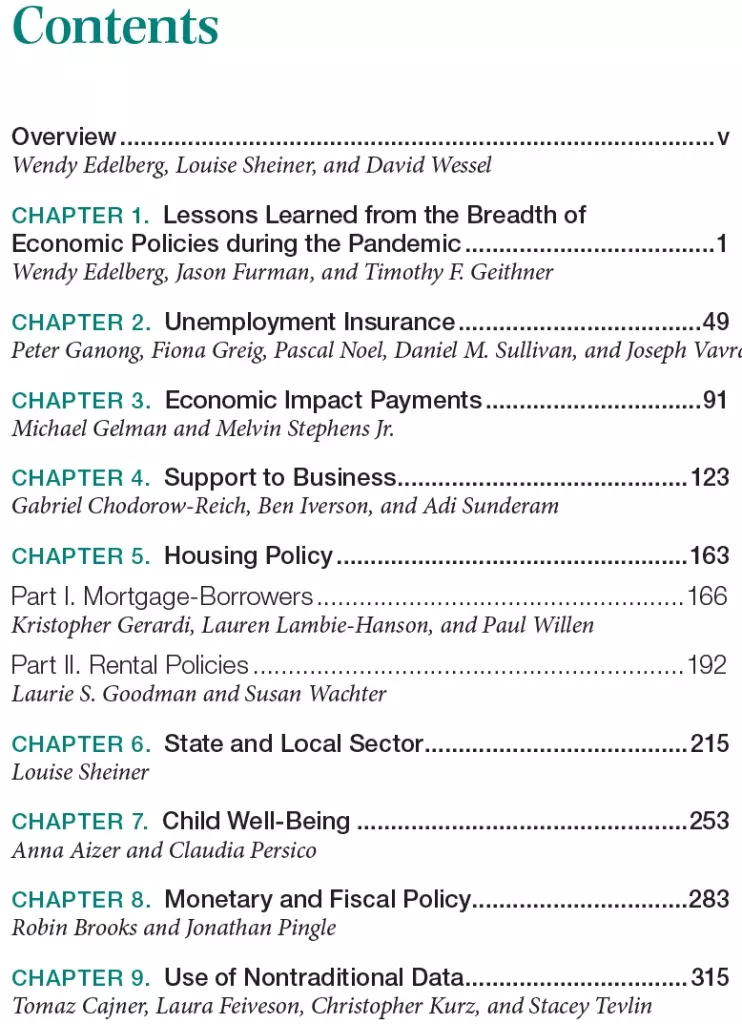

The book often returns to the theme that the next recession is likely to come from its own idiosyncratic cause–that is, not from a pandemic–and it is worth thinking about what policies might be put in place now that would kick in automatically when that recession hits. Here’s the table of contents for the book as a whole:

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest