Comments

- No comments found

There are no examples of countries with generally low levels of educational achievement that are also high-income nations; conversely, there are many examples of countries where the level of educational achievement first increased substantially and then was followed by economic growth.

Eric A. Hanushek and Ludger Woessman describe their recent research on basic skills around the world in “The Basic Skills Gap” (Finance & Development, June 2022).

Six stylized facts summarize the development challenges presented by global deficits in basic skills:

1. At least two-thirds of the world’s youth do not obtain basic skills.

2. The share of young people who do not reach basic skills exceeds half in 101 countries and rises above 90 percent in 37 of these.

3. Even in high-income countries, a quarter of young people lack basic skills.

4. Skill deficits reach 94 percent in sub-Saharan Africa and 90 percent in south Asia, but they also hit 70 percent in the Middle East and North Africa and 66 percent in Latin America.

5. While skill gaps are most apparent for the third of global youth not attending secondary school, fully 62 percent of the world’s secondary school students fail to reach basic skills.

6. Half of the world’s young people live in the 35 countries that do not participate in international testing, resulting in a lack of regular foundational performance information.

They write: “The key to improvement is an unwavering focus on the policy goal: improving student achievement. There is no obvious panacea, and effective policies may differ according to context. But the evidence points to the importance of focusing on incentives related to educational outcomes, which is best achieved through the institutional structures of the school system. Notably, education policies that develop effective accountability systems, promote choice, emphasize teacher quality, and provide direct rewards for good performance offer promise, supported by evidence.”

But what specific strategies might be most useful in addressing these issues in developing countries? Justin Sandefur has edited an e-book for the Center for Global Development, including six essays with comments, entitled Schooling for All: Feasible Strategies to Achieve Universal Education.

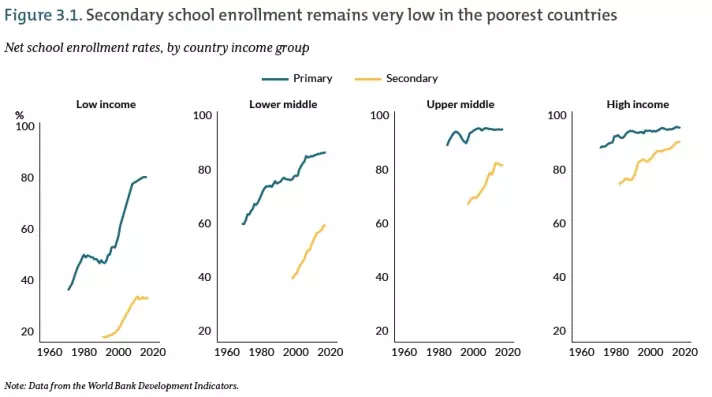

Around the world, many countries have achieved a substantial increase in primary school enrollment, but only a very modest increase in secondary school enrollment. In Chapter 3, Lee Crawfurd and Aisha Ali make “The Case for Free Secondary Education.” A lot of their proposals come down to the basics: more teachers and more schools. In many developing countries, students must pass an entrance examination before attending secondary school, and if they pass the exam, they then need to pay fees. Here’s the result:

A common concern–and one of the justifications for charging fees in secondary schools–is that many children from lowest-income families still face considerable barriers to success in primary school. Thus, free secondary school could tend to be a regressive program, benefiting mainly children from higher-income families. Thus, a challenge lurking in the background is how to support children from the lowest-income families in their primary education, so they are not already far behind as early as third or fourth grade.

Lee Crawfurd and Alexis Le Nestour look at the evidence on “How Much Should Governments Spend on Teachers?” They conclude that although hiring more teachers will be necessary if schooling is to expand, there isn’t much evidence that higher pay for the existing teachers will make a substantial difference in the performance of the lowest-income children in the early grades. In that spirit, the notion of feeding children in school comes up in several of the essays, and is the focus of “Chapter 2: Feed All the Kids,” by Biniam Bedasso. He writes:

School feeding programs have emerged as one of the most common social policy interventions in a wide range of developing countries over the past few decades. Before the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly half the world’s schoolchildren, about 388 million, received a meal at school every day (WFP 2020). As such, school feeding is regarded as the most ubiquitous instrument of social protection in the world employed by developing and developed countries alike. But school feeding is also a human capital development tool. The theory of change for school feeding programs is rooted in the synergistic relationship between childhood nutrition, health, and education underscored in the integrated human capital approach (Schultz 1997). The stock of human capital acquired as an adult—a key determinant of productivity— is supposed to be a function of the individual and interactive effects of schooling, nutrition, health, and mobility. … A survey of government officials in 41 Sub-Saharan Africa countries conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in 2016 shows that a great majority of the countries implement school feeding programs to help achieve education objectives. …

A review of 11 experimental and quasi-experimental studies from low- and middle-income countries reveals that school feeding contributes to better learning outcomes at the same time as it keeps vulnerable children in school and improves gender equity in education. Although school feeding might appear cost-ineffective compared with specialized education or social protection interventions, the economies of scope it generates are likely to make it a worthwhile investment particularly in food-insecure areas.

In short, Bedasso argues that feeding children at school in developing countries probably pays off just in terms of educational outcomes. But even if the payoff just in terms of education isn’t exceptionally high, the payoff to improved child nutrition in general takes many forms, including improved health and gender equity.

The case for feeding children at school seems strong to me. But it’s only one part of addressing the problem. Many developing countries have dramatically increased primary school enrollments, but they are not yet assuring that most children can keep up and actually achieve basic literacy and numeracy at the primary school level.

A related problem is that the money for this broader agenda is lacking. Jack Rossiter contributes Chapter 6, which is titled “Finance: Ambition Meets Reality. He looks at the costs of universal primary and secondary school spending, along with school meals, and concludes that the cost would be about $1.9 trillion for low- and middle-income countries in 2030. However, the projected education spending for these countries is about $750 billion less. Outside foreign aid might conceivably fill $50 billion of the gap, but probably not more. Rossiter makes the grim case:

Even if international financing comes in line to meet targets, governments are not going to have anything like the sums that costing exercises require. We can choose to ignore this shortfall, stick with plans, and watch costs creep up. Or we can see it as a serious budget constraint, redirect our attention toward finding ways to push costs down, and try hard to get close to universal access in the next decade.

It’s of course tempting to elide these tradeoffs. Maybe if we just root out waste, fraud, and abuse, we will have all the funds we need? Doubtful. As Rossiter points out, universal access by 2030 may require scaling back on the nice-to-haves–like smaller class sizes, higher pay for teachers, new classroom materials, and so on–and being quite hard-headed about the must-haves.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest